I haven’t blogged much lately. The reason for that is I’ve been finishing a draft of my book on the issue of the virgin birth (more technically: virginal conception). I’ll be saying more about that book in days to come.

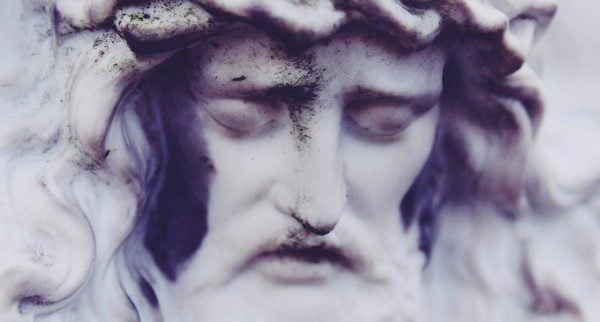

Through the process of writing this book I’m come to appreciate the humanity of Jesus in a much more powerful way. I’ve realized how much my evangelical background had instilled in me a picture of Jesus as divine — as the eternal Son of God, the Word, the Logos, the second person of the Trinity, etc.

But what about his humanity? The human Jesus of Nazareth so often gets swallowed up in the ocean of divinity.

James Barr, in his important book, Fundamentalism, suggests that the heresy of fundamentalism is the overplaying of Jesus’ divinity and the undermining of Jesus’ humanity — as he puts it, that Jesus was a “superhuman” or “non-human” person. He writes,

While traditional orthodoxy holds that Christ is both God and man, and while that position is taken by correctly-informed conservative apologists, the emphasis of fundamentalist religion falls heavily on the deity of Christ. He is indeed man [to fundamentalists], but the essential thing to affirm is that he is God.

This becomes stronger when one turns away from informed conservative apologetics and looks at the ordinary fundamentalist believer. He has probably never heard of Athanasius and knows nothing of the idea that Jesus Christ is equally God and man. What he believes about him is that he is God. He is God walking about and teaching in a man’s body.

Everyone knows that Jesus is a man, no virtue and no value is to be got from recognizing that he is a man; it is the recognition that he is God that counts, and that makes some difference…

The essential thing for popular fundamentalism is that Jesus is God. To put it negatively, and fundamentalist affirmations have to be seen negatively in order to see what they mean, any approach to Jesus that starts out from Jesus as man falls under suspicion and has to be rejected, unless it is immediately qualified with an even stronger assertion that he is God (169).

The net effect of the over-emphasis on the divinity of Jesus and the neglect or marginalizing of his humanity, is a perversion into an unorthodox view of Jesus. This perversion is of course ironic, given that it’s the fundamentalists who insist they they are the true orthodox believers.

This lop-sided Christology ends up affecting other beliefs too, such as the fundamentalists’ view of the atonement (often exclusively understood as “penal substitutionary atonement,” sidelining or neglecting other important atonement theologies and metaphors in the Bible).

It also impacts how fundamentalists read the Bible generally, with a penchant for harmonizing Scripture in order to fit their lop-sided emphasis on the divinity of Jesus.

The virgin birth stories are read literally (historically, etc.) and are interpreted as foundational–equal in weight to the resurrection accounts.

The gospels are flattened out by the presumption of the divinity of Jesus, and the many names (i.e. Son of Man) are interpreted through the grid of the “divine nature” of Jesus.

The presupposition of the “inerrancy of the Bible” is further underscored by the over-emphasis on Jesus’ divinity–for how could Jesus say anything “wrong” or untrue if he was God? And, since Jesus was God, the Bible which portrays and presents him must be absolutely flawless, too.

A practical implication of all this, too, is that fundamentalism relates to Jesus primarily through his divinity rather than his humanity, which creates an image of Jesus that is triumphalist and only marginally related to our human experience.