Technology is powerful, complicated, and dangerous.

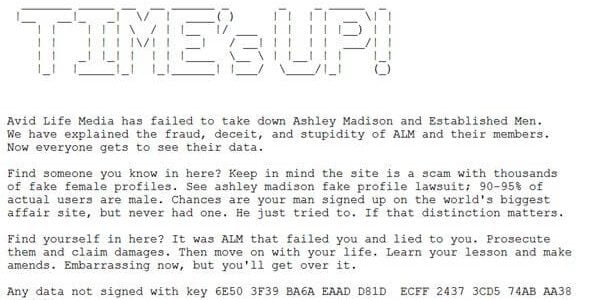

A lot of people who signed up for an account on Ashley Madison (the website that bills itself as dating site for married people…as in, for people who are looking to have an affair) are shaking in their boots right now.

The hackers who mined the data of 32 million (they claim) customers and former customers of the site have now fulfilled their promise/threat to post the leaked data. They did so yesterday, on the Dark Web. Investigators are pouring over the data to determine its validity. Early reports are that the data is in fact legit–among other fraudulent of “dummy” accounts, there are many real people with valid email addresses and credit cards (even many currently active cards in daily use).

The Telegraph has provided ongoing commentary on the unfolding events, noting that there will likely soon be a massive uptick in business for divorce lawyers. We could add there will also likely be an increase in work for marriage therapists. Hopefully the therapy business booms before the lawyers have their go at it. A tweet mentioned in the commentary also suggests that the credit card fraud departments will be busy too, racing to get in front of all that active data.

Computer security expert Graham Culley has written a blog post in which he provides some information that people should think about before they rush to any conclusions. Not all email addresses or even names are going to be valid (some email addresses might have been “borrowed” to keep the real user anonymous). Furthermore, given that 95% of the Ashley Madison users are male (many female accounts are false lures), it’s likely that most of the users never actually had an affair–at least not through the website.

But Culley also offers some reflection on the potential severity of the consequences for those who have been exposed as would-be cheaters, or who at least fantasized about the idea enough to sign up for an account.

Culley suggests that some might turn to suicide as a perceived better option than facing the embarrassment, disappointment, or conflict that will follow their exposure.

The potential severity of the consequences raises, in a very stark way, the issues of the moral culpability of the hackers. If and when a death does result (the odds do seem stacked in favor of the worst outcome), who will be responsible? The customer? The hackers? Ashley Madison owners/management? All of the above?

On first glance, one might think of the hackers as cyber-vigilantes for moral justice, transparency, and honesty. And yet, their stated motivations are not quite clear. Are they against marital infidelity? Broken promises? Or are they against the website’s practice of charging a fee for deleting accounts? Or is something else driving them?

I’m pretty much enthralled with the TV show, Mr. Robot, at the moment. One alternates between admiration,  revulsion, and empathy for uber-hacker Elliot and his f-society comrades. (It also makes you wonder who else might be reading your Facebook account–from the inside–and who else might be reading your emails?). Are they the new, brave, Robin Hoods, taking down the broken system of corporate greed and disproportionate power–through the best or only means available to them? To be fair, the show’s characters are more complex than that–and their respective, individual motivations not entirely pure, thoroughly noble, or even clear.

revulsion, and empathy for uber-hacker Elliot and his f-society comrades. (It also makes you wonder who else might be reading your Facebook account–from the inside–and who else might be reading your emails?). Are they the new, brave, Robin Hoods, taking down the broken system of corporate greed and disproportionate power–through the best or only means available to them? To be fair, the show’s characters are more complex than that–and their respective, individual motivations not entirely pure, thoroughly noble, or even clear.

The pilot episode, when Elliot hacks a pedophile/child pornographer and turns him in to the police via anonymous tip, brings a sharp point to the collision of moral values. Is illegally breaking in to the private life of another person a righteous act, if it brings someone to justice and protects vulnerable people? There are no easy answers here. Eliot is no caped crusader. His own personal identity is rendered as fragile, vulnerable, and broken as the identities he invades.

The show raises all sorts of questions at the intersection of global capitalism, economic disparity, and of course, whether vigilante computer hacking could be legitimated as a response to contemporary systemic evil. After all, just because something is illegal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s immoral or unjust. Even if an action is considered immoral, might the culpability of that immoral act be reduced or even eliminated altogether, if it is in service of the “greater good”–such as exposing and undoing a more severely immoral act or system? It’s the old question: Do the ends justify the means?

Just ask supporters of the “Center for Medical Progress,” that anti-abortion watchdog group that secretly taped Planned Parenthood. Hardly anyone seemed to question the means to the end, since the end was assumed by so many pro-lifers to be self-evidently righteous and necessary. But the moral implications of “hacking” Planned Parenthood through video-technology were worthy of more discussion than they received.

We are certainly living in complicated times–and of course we have been witnessing for some time the dizzying increase in the power, speed, and pervasiveness of technology–for better and for worse.

But the fallibility of human beings stays pretty constant. As technology marches on, so do our moral dilemmas.

For more posts and discussions on theology and society, follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook