Wolves will live at peace with lambs,

and leopards will lie down in peace with young goats.

Calves, lions, and bulls will all live together in peace.

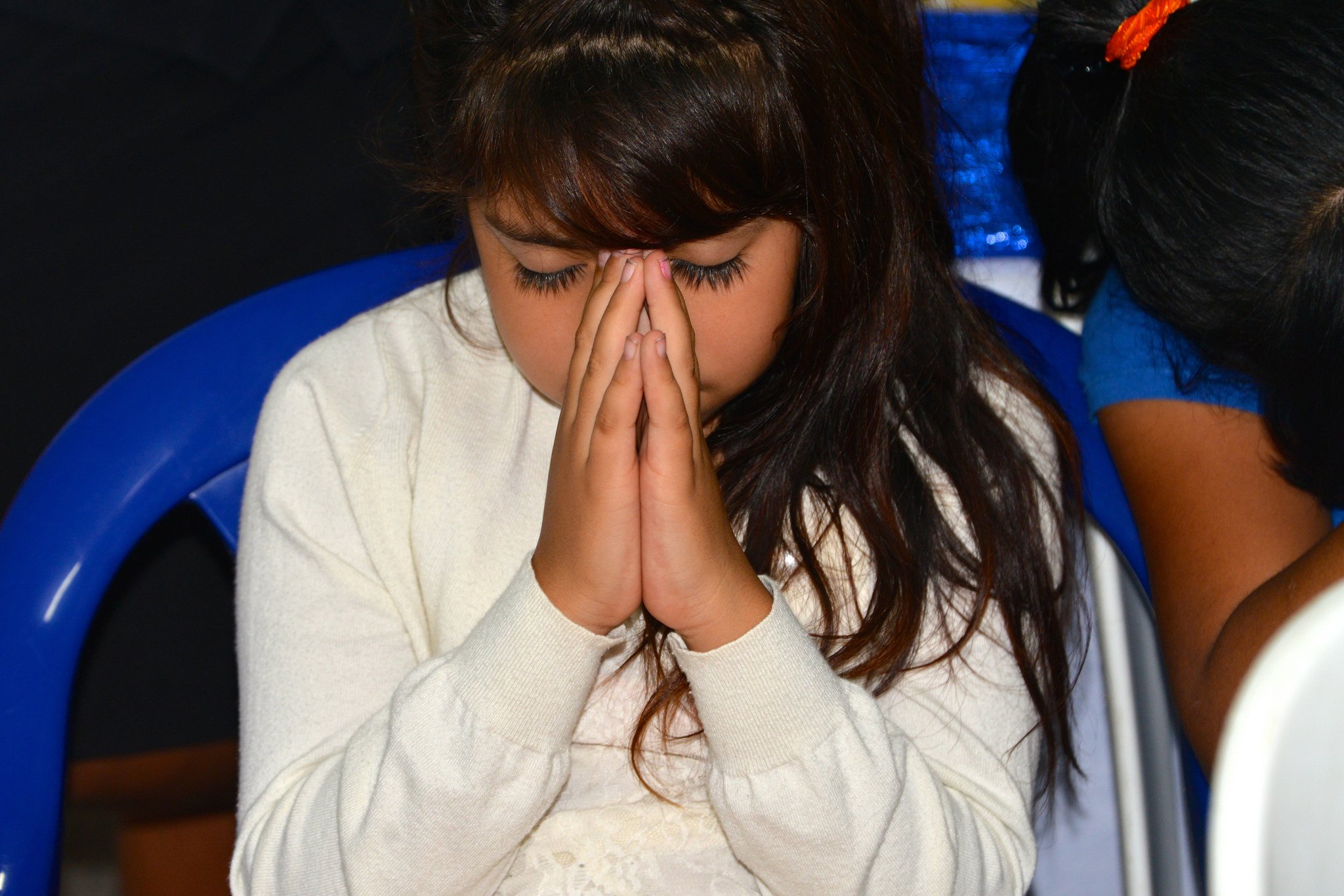

A little child will lead them.

.

Bears and cattle will eat together in peace,

and all their young will lie down together and will not hurt each other.

Lions will eat hay like cattle.

Even snakes will not hurt people.

.

Babies will be able to play near a cobra’s hole

and put their hands into the nest of a poisonous snake.

People will stop hurting each other.

~ Isaiah 11:6-9

Isaiah 11:6-9 contains some of my favorite poetry in the Bible. In this passage, we are presented with a stunning, overwhelming image of a world in which children are not only respected and giving positions of leadership. they are also protected from pain and hurt. In her essay on children and Isaiah’s prophecies, Jacqueline E. Lapsley writes, “God is telling Israel throughout the book of Isaiah that children are central to salvation. How children are treated, both in the present and in the future, is essential to the divine vision of what God would have for Israel. In the alternative world that Isaiah envisions, God is a tender mother, whose fierce maternal love outstrips that of every human mother for her children. In that world children are not sentimentalized but are claimed, named, and blessed. They are abundant and protected” (The Child in the Bible, p. 102).

While Isaiah was speaking prophecy to a specific group of people, I think his words are relevant to Christians today. For what Isaiah envisioned was a manifestation of the Kingdom of God. And as Jesus told us, “The Kingdom of God is at hand” (Matthew 3:2). The Kingdom of God speaks to the future, but eschatology tells us that this future can transform our present. As Gustavo Gutierrez once wrote, “Hope in the future seeks roots in the present” (A Theology of Liberation, p. 125). The Kingdom of God is not just for later; it is also for our right-here and right-now.

One way that we can manifest the Kingdom of God on earth is to work towards protecting children. Jesus has instituted a topsy-turvy kingdom where the first are last and the last are first and those considered least—children—are centered and prioritized. “Let the little children come to me,” Jesus declares, and “do not keep them away” (Matthew 19:14).

This is not an abstract command. The command to welcome children is no mere sentimentalization. It is not to be reduced to a Precious Moments scene. The command to welcome children is a radical call to put children in the center of our lives and our ministries, just as Jesus placed children in his midst while his disciples were arguing about the finer details of theology.

Jesus made the point that those finer theological details are nothing if they neglect the real, flesh-and-blood children around us. Furthermore, our theologies are worthy of drowning if they cause the children around us to be hurt: “It will be very bad for anyone who makes one of these little children sin. It would be better for them to have a millstone tied around their neck and be drowned in the sea.” If your theology does not lead to a better world for children, throw it away.

Throughout the Book of Isaiah, the prophet repeatedly condemns the people of Israel for failing to protect children. He first urges the Israelites that they need to “Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow” (1:17). Then he calls out the leaders of the nation for ignoring his words: “Your rulers are rebels, partners with thieves; they all love bribes and chase after gifts. They do not defend the cause of the fatherless; the widow’s case does not come before them” (1:23). So he prophetically critiques those leaders: “Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless” (10:1-2).

I think it is interesting that Isaiah does not merely critique the people of Israel for failing to protect children. Instead, he lays the blame at the feet of the people’s leaders and the laws they make: “your rulers are rebels,” he proclaims, “who make unjust laws.” “Those who issue oppressive decrees” are the ones “making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless.” In other words, the anti-child attitude prevalent during Isaiah’s time was more than individual failure. It was a matter a systemic injustice.

In this anti-child context, Isaiah’s poetic vision in 11:6-9 stands out in sharp contrast. It brings into even greater relief his vision of a world which child protection is a primary concern. The world that Isaiah describes is one where children are protected. Children are protected not only from dangerous animals. They are also protected from dangerous adults: “People will stop hurting each other.” Isaiah is envisioning a world free from child abuse and neglect. This tells us that fighting against child abuse and neglect is part and parcel of realizing the Kingdom of God in our right-here and right-now.

Isaiah reveals how this unfolds: with little children in the lead. In our contemporary faith communities the little children might be those who were and are hurt by adults. Child abuse survivors have walked through the fire and come out alive. They are living witnesses to the pain and terror of child abuse and neglect. They bear the scars of the wolves in our churches who have violated their bodies and souls. While the Kingdom of God is upon us, we have not realized it yet. In our right-here and right-now, wolves are dangerous to lambs. Abusers prey upon children.

We must, therefore, listen to the children and child abuse survivors around us. We must heed their cries and we must believe them when they tell us they were hurt. We must let them know they can trust us with their stories and we must not betray their trust with shaming them when they speak up.

It is through relationship with such children and survivors that we can build safer communities. These children and survivors have much to teach us. They can instruct us about the warning signs of abuse they exhibited, how their predators groomed them, how abuse created or exacerbated mental illnesses, how abuse hurt their faith, how to respond properly to abuse, how to secure our communities against future predators, and how to make survivors—today, after a childhood of abuse—feel safe and welcome in our contemporary faith communities.

If we are going to build safer communities, we need to stop talking—talking about false accusations, about Matthew 18, about the necessity of forgiveness, or whatever else we talk about to justify why we are not listening. We need to humble ourselves and learn from the disciples around Jesus who were so busy with arguments that they missed the chance to love and protect the actual children in their midst. We need to start prioritizing children like Jesus did. That prioritization means passing the microphone; it means letting children and abuse survivors lead us, just like the little child leads in Isaiah’s prophecy.

The Kingdom of God is a kingdom of children. It is a kingdom where children are loved and protected. It is a kingdom of child liberation.