This is a guest post by Christian H of The Thinking Grounds, and is appearing here as part of our symposium on Loving Parishioners in their Particularity – discussing how the church community can focus its approach on serving people in different life circumstances.

In the US, about 3 to 5% of people—averaged over age, sex, etc.—have depression, and about 17% will have depression or have had depression. (I’m not American, but I imagine the statistics are comparable in most WEIRD countries.) Church-goers might not represent the total population, but these numbers are still high enough that your parish will almost certainly have some members with depression; the odds are even pretty high that someone in the pews this week currently has depression. I don’t want to encourage anyone to be paranoid, but here’s the thing about depression: it’s invisible. Anyone in your parish might have depression. That grinning, joking senior you’re talking to about the local transit lines? That new parishioner helping out in the kitchen? The flirtatious lay administer? Any of them might have it. While there are symptoms, they vary from individual to individual and most of the time people can hide them well enough. In fact, they almost certainly will try to hide them. So when it comes to making churches welcoming to people with depression—well, the first thing you have to know is that anyone might have depression and someone almost certainly does.*

So, with that in mind, what should you do? I have a few ideas; I think most of these are things we should be doing anyway and they’ll have nice curb effects.

- Get used to the idea that we’re lying to you. If people ask me directly, I will tell them I have depression. Otherwise, I won’t bring it up. I smile, laugh, and act friendly. Other people go to greater lengths to hide it. There are lots of reasons to be afraid about people knowing you have depression. Remember that all of the hiding and lying isn’t about you; it’s about us and our comfort levels. (Well, actually it might be about you—see the next point—but it also might not.)

- Welcome complaints and misery. Let people gripe and whine. Let people grumble. Don’t avoid pessimists, cynics, and sad-sacks. Don’t ask them not to complain. Complaining might be the only way they have of expressing themselves with you. I know I sometimes gripe to test how people might react to the news that I have depression.

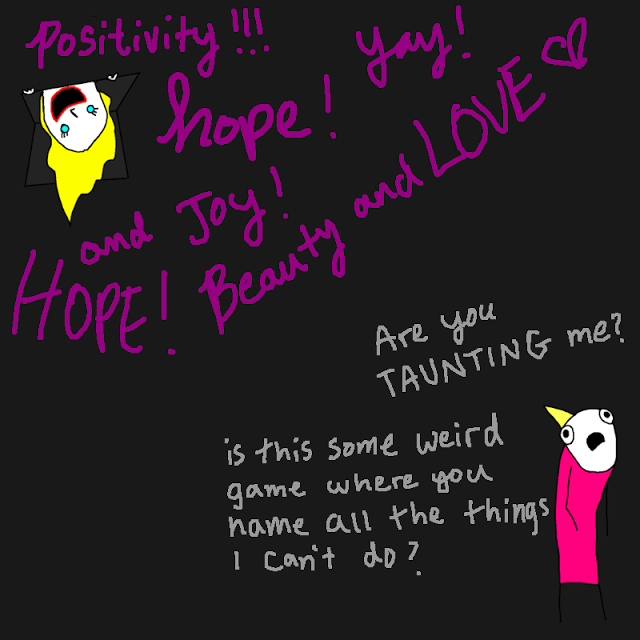

- Recognize that a lot of Christian language is alienating to someone with depression. I’m not asking you to re-write the liturgy or the Bible to avoid references to hope or declarations of joy. And I’m not asking you to stop expressing your own hopes and joys. But I am asking you to stop suggesting that other people ought to feel hope or joy in response to God’s abundance/mercy/whatever. We might be literally unable to feel those things. Being the only miserable person in the midst of unreserved praise is an alienating and isolating experience. Try not to make them feel guilty or defensive on top of that by suggesting they should feel differently. A lack of joy does not indicate a poor relationship with Christ. [ed note: I recommend this Hyperbole and a Half comic (the source of the image up top) on this point –LL]

- Don’t judge people’s attendance patterns. One thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of people really expect regular church attendance. They might even suggest that church attendance indicates the quality of your relationship with Christ (literally, I have heard this). But when you’re depressed, mornings are especially difficult—part of it is sleep’s effect on brain chemistry; part of it is that sleep is really seductive to a person who is miserable whenever they’re awake; part of it is that people with depression often have insomnia and cherish whatever sleep they get. If you’re a depressed churchgoer, this can be emotionally trying, because you might really want to go to church or you might already think you’re scum because you aren’t going to church (that’s depression, eh?), but neither of those things actually help you get to church. So, if you see someone whose attendance is irregular, don’t suggest they should come more often. They probably agree with you and that’s making them even more miserable.

- Be careful when relating sin and error to mental illness. I feel like this goes without saying, but apparently it’s necessary. Referring to sin or bad ideas as signs of mental illness (“That’s crazy talk!”) is not helpful. I’m not asking you to avoid noticing and discussing psychology; exploring how responses to mental illness might also help us be more considerate or less wrong can be done well when nuanced, respectful, and informed. It can also be done very very badly. Directly comparing sin and error to mental illness directly compares mental illness to error and sin. Mental illness is neither.**

- Be really careful when talking about suicide. I’m not going to ask you to lie, but you do need to be quite thoughtful. If you suggest that suicide is an act of ingratitude or an attempt to annihilate the world,*** you are going to saddle anyone who has suicidal impulses with shame they really do not need. Remember that suicidal thoughts are intrusive and not usually volitional. When a person’s suicidal thoughts are partly a result of feelings of guilt and shame, then guilt and judgement will not help them. Please be careful.

- Realize that you might not be able to help in the way you think. If someone does tell you about their mental illness, don’t expect to fix it. You can’t. And they might not want help from you; too many offers of support can be overwhelming. Follow their lead on this. Listen them. (Though, of course, sometimes you do have to intervene. It can be tough to judge.)

- But seriously though, listen them. That should get its own entry. Just because a person has a mental illness doesn’t mean that they do not know what they need or that they do not have wisdom to offer or that they can’t help you with your problems. (They very well might know not what they need or they might not have wisdom that’s of any use to you, but that’s true of everybody.)

- Offer help to everyone in general. Rather than seeking out people with depression so you can offer help to them in particular, make lots of opportunities for people to come forward. Have an afternoon service/Mass at your church if you don’t already, for those who can’t manage mornings. Run support groups or post contact information for certified counsellors. (Post them in places where people can copy down the number, or tear off the slips, without being seen.) Fight stigma. Take time to express your awareness that depression is real, that mental illness is never chosen, and that you will support in any way possible—but only do this if you know what you’re talking about. So learn about depression and correct your misconceptions; Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon is about the best book on depression I could find, if you want a place to start. Let people know that, if they come to you with their depression, you’ll offer realistic, compassionate, and informed support, and let them know that they’re welcome to stay in the church without disclosing their illness, too. It’s not enough for this to be true; parishioners with depression need to know that it is.

—

* It might be the priest, by the way. Remember that at the next committee meeting. Oh—and it might be you. I had a mood disorder for years without knowing it, and I was at least a month into an episode of moderate-to-major depression before I realized it.

** Of course, beliefs might be disordered. Ideology and pathology are sometimes tightly wound together. I’m not denying this, or asking you to deny it. But speak on this issue only with knowledge and nuance, OK?

*** Suicidal impulses can come from despair of the world or from despair with oneself. But even if it is the former, it still seems to me an alternative to destroying the world, not attempt. Sometimes. Sometimes it is an attempt to destroy the world. Just stop generalizing. That’s my point.

[ed note: one other possibly helpful resource, for yourself, or for informing allies, may be Richard Beck’s framework of Summer and Winter Christians, as a corrective to the idea that, if you’re not happy, you are doing your spiritual life wrong and need to fix it somehow, now – LL]

Make sure to keep checking the index post for our Loving Parishioners in their Particularity symposium, as new posts are being added every day!