Sarah Sparks has a really excellent post today at First Things about the interactions (good and bad) between theology and therapy. As an Orthodox Christian and a recovering bulimic, Sarah has has to do a lot of translating between the sacred and the secular, since the treatment of sin, fasting, and self-control are very different in each of the two worlds she moves in. It looks like both groups have a lot of cultural false cognates — moments where they’re using the same word to refer to different ideas.

This brings us to the concept of control. Within the Orthodox spiritual tradition, control is linked to a sense of mature self-mastery. However, eating disorder treatment professionals view control almost exclusively as a symptom of illness. Many people with eating disorders use control over food as a strategy for coping with chaotic experiences such as trauma, major depression, and changes occurring in the body.

Thus, Orthodox Christians recovering from eating disorders live at the intersection of the recovery community and the community of Orthodox believers, finding themselves constantly needing to discern the exact messages that each community intends in order to pursue healing, wholeness, and theosis.

When an Orthodox Christian in recovery tries to explain why members of the Orthodox Church fast, he is extremely careful to frame the issue appropriately within a treatment setting. Take, for instance, St. Basil who says, “Nothing subdues and controls the body as does the practice of temperance. It is this temperance that serves as a control to those youthful passions and desires.” Treatment professionals respond by emphasizing how surrendering control is absolutely necessary in order to recover from the eating disorder. With divergent meanings of control, the Orthodox Christian feels torn between faith and recovery.

Because another symptom of eating disorders can be seeking messages to glorify destructive behaviors such as restriction, a person struggling with anorexia or bulimia could understand certain advice from the Fathers on fasting as glorifying eating disorder behavior. Instead of continually exalting self-control, Orthodox Christians providing pastoral care might better refer to St. Seraphim of Sarov: “One should make use of food daily to the extent that the body, fortified, may be the friend and assistant of the soul in the practice of virtue. Otherwise, the soul may weaken because it is exhausted.”

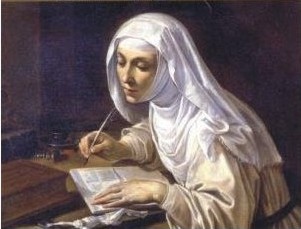

Outside of directed studies, one of the classes I took that had the strongest claim for “best syllabus” was my summer class on American epidemics in the history of medicine department. One of the many great books we read was Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa by Joan Jacobs Brumberg, which paid attention to the medical, cultural, and theological significance of fasting, and fasting that becomes pathological. (I’m pretty sure this was the first place I came across the name ‘Catherine of Siena’).

I don’t see people mention anything related to extreme eating in hagiographies of closer-to-modern saints (but commenters, please correct me if I’m wrong). I wonder is one reason that this has faded is because all eating has become more extreme in cultures where we do have enough to eat. Fasting from meat or bread or solid food isn’t going to be recognized as humble or (in Catherine’s case) as being focused on a higher kind of sustenance, when so many people are talking up strange diets for their material effects.

I’d love to see Tristyn Bloom expand her writing on holy fools and take up the question of what kinds of foolishness (if any) are now too common to be received prophetically. It seems like a modern stylite would immediately be lumped together with endurance artist David Blaine or, worse, the 300 Sandwiches kind of stunt blogs that are clearly trawling for a book deal. Are we too glutted with spectacle for most kind of witness to draw our attention past the person enacting them?

While I wait (and hope) for Tristyn to weigh in, I can point you to one secular consideration of how culture can be as infectious as disease, changing our understanding of pathology. The Last Psychiatrist describes how anorexia in China homogenized itself to resemble the Western strain of the disease. Then the blogger goes on to illustrate how the stories we tell about a disease change the healthy as well as the sick:

A subject tried to silently train a second person to press some buttons in a specific order. He is told that the second person had a psychiatric disorder either due to “life events” or to a “brain disease.” The only feedback they could give was to administer a very mild shock, or a very big shock, when the second person got the pattern wrong.

When the subject was told that the second person had a psychiatric disorder due to life events, they got the mild shock. When it was due to a brain disease, they got the big shocks. If there is already something wrong with their brain, the subject figured he had to make things obvious.

The point of this example was to illustrate that other cultures may end up stigmatizing the mentally ill if they begin to incorporate the Western idea that these are strictly brain diseases. Too late: incorporating the western idea was what gave them the disease in the first place.

All the more reason to do Sarah’s work of examining the different stories we’re telling and sifting the weeds from the wheat.