The theme for this week is distortions or odd perspectives on space and time. First up is photographer Adam Magyar, who repurposes a photographic technique. As described by Matter:

Digital photography, first developed in the 1970s, gave rise to two types of image-capturing devices: standard digital cameras and scanners. The former captures an entire subject in a single exposure. The latter, by contrast, captures an image in a sequence. The sensor moves over the subject—a printed document, for example—and photographs it line by line, then assembles a composite image. Scanners, graphics-editing programs, and high-speed industrial video cameras have allowed conceptual artists to break the bounds of conventional photography and become increasingly abstract and surreal.

Instead of scanning an object, Magyar has been pointing his homebrew scanner camera at subways and crowds, with arresting effects. The video below pans along a photograph he took of a NYC subway platform from a moving train.

We rely on language to situate ourselves and our stories in time and space, but, unless you took a foreign language class, you may only have a fragmentary understanding of how grammar classifies and structures our verbs. Over at his blog, Anthony Esolen has a quick, cogent explanation of what deponent verbs are:

Many of these verbs, though, really do occupy a middle space between active and passive. They are like Greek verbs in the middle voice, in which the subject is both acting and acted upon. Consider these sentences:

I hurt the quarterback.

I was hurt by her remark.

I hurt.Notice the differences between the three? In the first, the true active voice, the subject is the agent of the verb. In the second, the true passive, the subject suffers the action of the verb. But in the third – what? The subject is the agent, because he’s actively experiencing something named by the verb; but he suffers the verb. “I’m hurting” does not mean “I am walking around the neighborhood punching people,” but “I am feeling hurt; something is hurting me.”

You follow?

And now to warp space, or at least our expectation of the matter that fills it: oobleck! Oobleck is a suspension of cornstarch in water, was named for a Dr. Seuss book, and, most importantly for our purposes, is a non-Newtonian fluid. Oobleck normally flows easily, but, if you apply sufficient force, it acts more like a solid.

That means you can walk across its surface… or rather you can run. The dawdlers will sink and be engulfed. (‘Justly,’ thinks the New Yorker).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-wxnID2q4AI’ve often thought that oobleck would make for a good, trendy gym class. Each student gets a bucket of oobleck and just has to keep moving enough to stay atop the surface for an hour.

On January 1st, economist Tyler Cowen celebrated Public Domain Day — the day when classic works would have entered the public domain, were it not for intellectual property laws continually being rewritten to keep them out of our hands. This year’s crop

- Samuel Beckett, Endgame (“Fin de partie”, the original French version)

- Jack Kerouac, On the Road (completed 1951, published 1957)

- Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

- Margret Rey and H.A. Rey, Curious George Gets a Medal

- Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel), How the Grinch Stole Christmas and The Cat in the Hat

- Ian Fleming, From Russia, with Love

After another round of updates, these works are verboten until 2053. And that’s if their estates don’t successfully lobby for another extension.

On the plus side, since the Sherlock Holmes stories straddle a public domain timeline, a judge has ruled that some of them are available to play with, but presumably derivative works can’t make use of character details revealed in later stories.

P.S. Who’s watching season 3 of Sherlock? Can anyone think of a good blackmail-related food I can make for the finale party this Sunday?

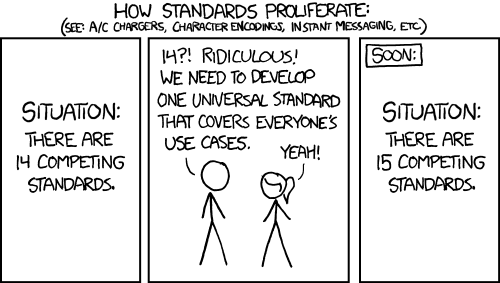

The next link is a bit of a stretch for the theme, I suppose, unless you consider that when your computer mangles the character coding of a website, the bizarre symbols that appear seem to have been put through a strange, metamorphic process. Whatever the excuse, I really enjoyed reading this history of unicode, ascii, and the other codes that help your computer convert numbers into letters and symbols.

I was also reminded of this xkcd:

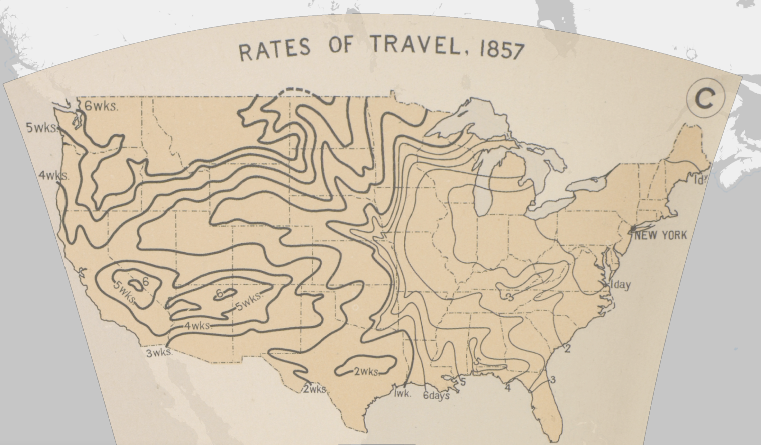

Ok, so the next link actually has “Travel Time” option right on its homepage. The Atlas of the Historical Geology of the United States has stitched together U.S. maps so you can watch the spread of canals or a network of railroads knitting together or, one of my favorites, isolines tracing out travel times to different parts of the U.S. from NYC.

And finally, if you want to warp our understanding of reality (or be on your guard against people who do), you want to read Scott’s summary of Dark Side Statistics.

[T]here are lots of tricks unscrupulous or desperate scientists can use to artificially nudge results to the 5% significance level. The clarity of the presentation is unique. [This paper] start[s] by discussing four particular tricks:

1. Measure multiple dependent variables, then report the ones that are significant. For example, if you’re measuring whether treatment for a certain psychiatric disorder improves life outcomes, you can collect five different measures of life outcomes – let’s say educational attainment, income, self-reported happiness, whether or not ever arrested, whether or not in romantic relationship – and have a 25%-ish probability one of them will come out at significance by chance. Then you can publish a paper called “Psychiatric Treatment Found To Increase Educational Attainment” without ever mentioning the four negative tests.

It does not get less depressing from there, especially since later in the post, you’ll hit the following sentence:

The image demonstrates that by using all four tricks, you can squeeze random data into a result significant at the p < 0.05 level about 61% of the time.

So, um, have an ok weekend?

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!