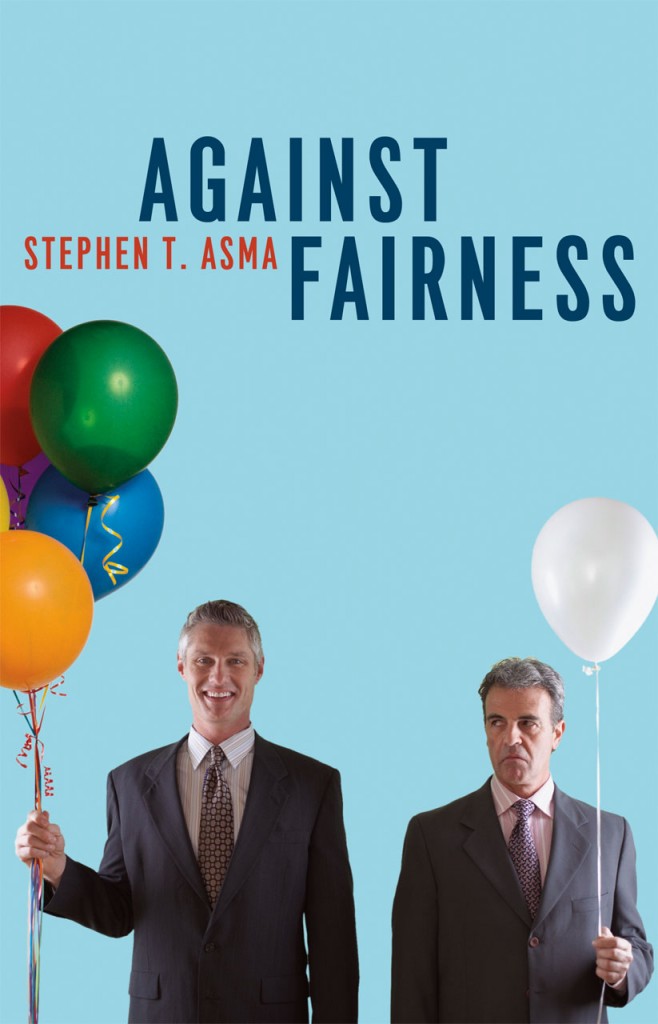

The newest issue of Fare Forward is out, and I have a review of Stephen T. Asma’s Against Fairness in the magazine. You can read the review in full on Fare Forward‘s website, but here’s a teaser:

Stephen T. Asma’s book is titled Against Fairness, but it doesn’t take too long for the reader to discover what he is for. Asma thinks we’ve neglected nepotism, favoritism, and particularity in our relationships and our moral reasoning. Our natural impulse to play favorites is, in his opinion, actively suppressed: children have to bring in Valentine’s cards for the whole class, fast-tracking a friend in a job search is unethical, etc.

In a world fixated on fairness, Asma turns to fiction to show us a positive view of particularity:

Many folk tales, fairy tales, and contemporary kids’ stories reveal and even lionize favoritism…

The Velveteen Rabbit… convey[s] the idea that loving something or someone intensely enough can actually change the beloved’s metaphysical status.

And that last line ought to sound pretty familiar to Christians. Christ’s love for us is enough to change our metaphysical status, from mere creatures to adopted sons and daughters of God. And it would be bizarre to view Christ’s sacrifice through the lens of fairness. As an act of grace, it was unmerited. But, in our own lives, and our own relationships, things aren’t that unequal, so how should we think about egalitarianism?

You’ll have to head over to Fare Forward to read on, and, when you’re done, you might want to also check out Helen Rittelmeyer’s review of the same book for First Things. I’m sure Asma would approve of my particular fondness for her writing; here’s how she leads off:

Stephen Asma buries in the endnotes of Against Fairness the information that he is from Chicago, but I think it ought to be mentioned up front. His book is a counterintuitive defense of favoritism, nepotism, tribalism, and patronage, and no place in America clung to these outdated habits longer than the Windy City. Decades after historical forces had planted the kiss of death on Tammany Hall and all the other famous urban political machines, Chicago was still the town of “We don’t want nobody nobody sent,” and while the rest of the country considered the Cook County machine a national disgrace, native Chicagoans have always worn their city’s distinctive political culture as a badge of pride, corruption and all.

Asma’s background is doubly fortunate because, in a strange turn of events, the fault line that defined twentieth-century Chicago politics has come to dominate an important front in the culture wars. The struggle between the Daley machine and the “good government” reformers was essentially a fight between skeptics of fairness and worshippers of it.

It’s interesting that Jonathan Haidt ran into the most troubles with his Fairness pillar in his Moral Foundations Theory (described in The Righteous Mind). His original prompts to see how important fairness was to his subjects presupposed that fairness was about equality not proportionality. Making sure people “get what they deserve” requires us to answer the hard questions about what the nature of humans is and what duties that implies. And that question isn’t any easier in particular than in general.