This post is part of a series on Aquinas, Aristotle, and Edward Feser’s explanation of them both.

Back to Feser and Aristotle for a bit. Later on in The Last Superstition, Feser talks about some of the obvious final causes we can observe. He’s using this section to defend natural law against the accusation that it’s proponents want us to go back to pre-modern technology and to set up his attack on homosexuality. I’m not interested in those points, so you can look them up yourselves. I want to discuss what his theory implies about transhumanism and teleology. Feser writes:

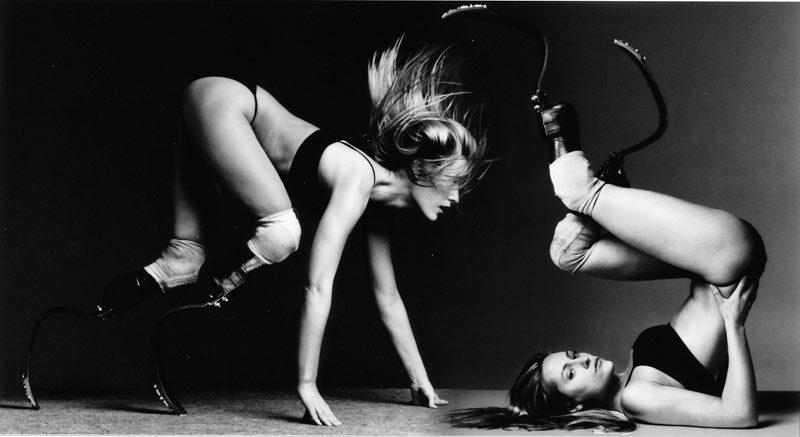

When we get to biological organisms, we have things whose natures or essences more obviously involve certain final causes or purposes. So, for example, the function or final cause of eyeballs is to enable us to see. But suppose someone’s eyeballs are deficient in some way, making his vision blurry. In that case, to wear eyeglasses isn’t contrary to the natural function of eyeballs; rather, it quite obviously restores to the eyeballs their ability to carry out their natural function. Bicycles don’t do this, of course, but they do extend, rather than conflict with, the ability of the legs to carry our their natural function of allowing us to move about.

I think of the final causes Feser is describing (seeing, moving) as being hugely subordinate to other goals (perceiving, ability to interact with parts of the world non-adjacent to me). There’s not automatically a virtue in my current means of achieving those goals. Without the ability to hear or vocalize, I can still talk if I know ASL. Oral and signed languages have strengths and weaknesses, but both will serve. A bicycle might get me places faster, and so might swappable bionic legs.

I assume Feser is only ok with supplementing, not replacing the human body, but (as you might expect) I’m willing to go further. There might be final causes that aren’t well served by my current form, so I’d like to adapt it. There is one big difficulty with my position though.

If you believe the human body has an inherent dignity, and that our form directs us to the correct final cause, you can bootstrap yourself from observations about your body to hypotheses about your telos. If, like me, you see the body as optimized and arbitrary, I have to find a different foundation for my claims about ought; the Aristolelian framework won’t get me all the way there.

That’s my dilemma, and I’m not sure Feser has earned his escape route from it. To really honor the human body and not want to tinker with the form, I think you need to oppose evolution, or, at the very least, believe God put a very heavy thumb on the scale when it came to criteria for fitness. The worthiness of our physical form has to come from somewhere, since I don’t think our experience with our meatsuits and our anthropologic data show it as good in itself.

This post is part of a series on Aquinas, Aristotle, and Edward Feser’s explanation of them both.