This post reflects upon the ‘death of God’ and how various depictions in paint, poetry, and prose can either serve to extinguish or enhance faith. Those whose faith will be enhanced through encountering the “Dead Christ” will find that Jesus assumed the very worst of our human condition to bring holistic healing.

Friedrich Nietzsche: “God Is Dead”

Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in The Gay Science that God is dead and we have killed him: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” In his estimation, this realization was a cause for celebration. Humanity must rise to new heights. For Nietzsche, we must now come to terms with this reality, rejecting the morality associated with the Christian God and its elevation of the foolish and the weak. He claims that in its place, we must elevate the aristocratic spirit involving intellectual-moral superiority and strength.

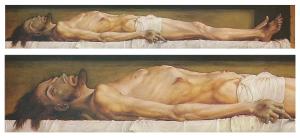

Hans Holbein: “Dead Christ”

Speaking of the death of the Christian God, I wonder if Nietzsche ever viewed the painting accompanying this post. Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting, the “Dead Christ,” hangs in the Kuntsmuseum Basel. Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky and his wife Anna visited the art museum in 1867 two years before Nietzsche took up his professorship at the University of Basel.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: The Idiot

The painting left such an impression on Dostoyevsky that it makes its appearance in his novel, The Idiot. Dostoyevsky wonders out loud in The Idiot if the disciples would still believe if they had witnessed such despicable horror in the tomb depicted in this painting. I encourage the reader to access the following three accounts of Dostoyevsky’s engagement with Holbein’s masterpiece (here, here, and here).

Charles Taylor: Pictures of Reality

Paintings often make lasting impressions on us. Similarly, we construct pictures of reality that often go unchallenged. In A Secular Age, Taylor writes of constructions of reality as “pictures” that “cannot be challenged.” (566) The ‘death of God’ historiography associated with Nietzsche and many others is one such picture or imaginative portrayal of life. It seeks to convince people that modern science and accompanying adulthood require believers to renounce faith in God. According to this historiography’s proponents, belief belongs to a childhood state of existence wrapped in the illusion of a benign and benevolent deity. (561)

Without in any way wishing to diminish science’s import, Taylor is by no means convinced that God is dead and that we must proclaim his demise. A conceptual picture that is not subject to debate is hardly the stuff of hard proof. If anything, it raises a host of questions, just like belief in God does. (See for example Taylor’s account of the death of God under closed world structures in A Secular Age, 560-570.) Such questions can also serve to ignite and cultivate faith.

The “Dead Christ” and Enhancement of Faith

The various accounts of Dostoyevsky’s fascination with Holbein’s “Dead Christ” referenced above, along with his reflection on the painting in The Idiot, suggest that it did not extinguish his faith. In fact, it appears that his experience gazing at the painting enhanced it.

The Assumed Is Healed

The painting likely helped Dostoyevsky come to terms more fully with the claim that Jesus assumed our full human condition. Christian orthodoxy requires the full or emphatic affirmation of what Holbein’s painting and Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin in the novel convey each in their own way: “the very worst of us has been assumed; only because this is so, can we all be healed.”

I believe the painting and storied presentation of Christ’s death can fan into flames one’s faith. My hope and prayer are that each of us will come to this realization, and increasingly so. The more we recognize Jesus’ assumption of the very worst among us—and in each of us—the more we truly experience holistic healing in relation to God and others.

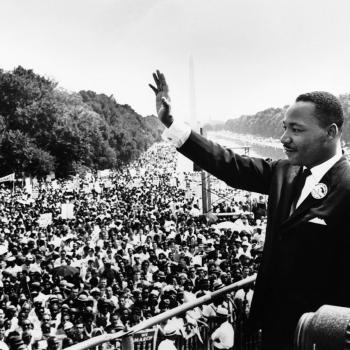

God’s Love and Our Attractiveness

If I am honest with myself and with you, I find that this is a very bitter pill to swallow. All too often we wish to see ourselves as noble and ideal humans, not those in great need of God’s radical mercy and the beneficiary of God’s love of the unlovely. But as Martin Luther wrote in the “Heidelberg Disputation,” God’s love creates our attractiveness. Our seeming attractiveness does not inspire God to love us.

Holbein’s painting, Martin Luther, and Lutheran pastor, theologian, and ethicist Dietrich Bonhoeffer each in their own way help us come to terms with this reality. Bonhoeffer writes in Ethics:

God becomes human out of love for humanity. God does not seek the most perfect human being with whom to be united, but takes on human nature as it is. Jesus Christ is not the transfiguration of noble humanity but the Yes of God to real human beings, not the dispassionate Yes of a judge but [the] merciful Yes of a compassionate sufferer. In the Yes all the life and all the hope of the world was comprised. In the human Jesus Christ the whole of humanity has been judged; again this is not the uninvolved judgment of a judge, but the merciful judgment of one who has borne and suffered the fate of all humanity. Jesus is not a human being but the human being. What happens to him happens to human beings. It happens to all and therefore to us. The name of Jesus embraces in itself the whole of humanity and the whole of God.

Holbein, Luther, and Bonhoeffer are in good company. Paul writes in Romans: Christ died for us while we were still God’s enemies (Romans 5:10). A few verses earlier, Paul writes that Jesus did not die for the righteous, but for sinners like you and me: “You see, at just the right time, when we were still powerless, Christ died for the ungodly. Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous person, though for a good person someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” (Romans 5:6-8; NIV)

Christ’s Assumption and Our Acceptance

Now if this is how God approaches us, how will we approach one another, including the seemingly noble and ignoble? What lasting impression might this vision of reality make on our spiritual imaginations? Paul provides an answer to this question several chapters later in Romans: “Accept one another, then, just as Christ accepted you, in order to bring praise to God.” (Romans 15:7; NIV)

When we come to terms with the reality that Jesus died for us—God’s enemies, the ungodly, we will be in a much better position to see ourselves for who we truly are—deeply loved by God. We will also be in a far better position to accept one another as deeply loved by God. Only as we come to terms with the dead Christ recounted in such works as Paul’s Epistle to the Romans and Holbein’s painting will God’s love truly break through to us. Rather that find faith extinguished, we will find faith enhanced whereby we experience spiritual and relational healing with God and one another in the community of faith.