This post reflects on how we can move from enduring victimizing life circumstances to victorious living. On Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, I engage Rashi, Viktor Frankl, Charles Taylor, the resurrection stories of Jesus, and the account of Joseph with his brothers, to develop this claim.

Jewish Suffering, Resilience, and Creativity

The Jewish community has certainly endured incredible suffering and trauma throughout their history. Amid innumerable horrific ordeals, they have often demonstrated incredible resilience and creativity, and have grown through their immense struggles.

Rashi: Isaiah 53, Suffering, and Atonement

One example of such resilience and creativity is rabbinic leadership and scholarship. The Jewish scholar Rashi’s interpretation of Isaiah 53. Rashi (Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac) originally maintained that the suffering servant in Isaiah 53 was an individual messianic figure. But later, he interpreted the suffering servant as Israel. The Jewish people’s suffering serves to atone for the sins of the Gentiles. Two of the reasons for Rashi’s interpretation were: to shield the Jewish community from Christian apologists who identified the suffering servant as a messianic individual, which they believed is Jesus; and to find a reason for why the Jewish community had undergone such incredible suffering during the First Crusade. (Refer here to Joel Rembaum’s article on this subject) Of course, the interpretation of Isaiah 53 is open to debate. But what cannot be denied is the resilient and creative effort to help lead the Jewish community forward to find meaning amid extremely challenging life circumstances.

The October 7th Atrocity and Yom Kippur

Discussion of the atonement is timely. The Jewish calendar observes Yom Kippur, that is, the Day of Atonement, on October 11 and 12 this year. Jewish people throughout the world observe Yom Kippur, which today emphasizes prayer, repentance, forgiveness, changed lives and, for those who may take Rashi’s view, the Jewish community’s suffering itself is atoning. Such suffering continues. Here it is worth noting that, just this week, two rabbis reflected on the October 7th atrocity in Israel last year, noting that it, like Yom Kippur, will forever be part of the Jewish collective memory.

Viktor Frankl: Suffering and Meaning

People respond to suffering, trauma, and tragedy differently. Many seek to find a meaning in their suffering. Viktor Frankl, psychiatrist, neurologist, and Holocaust survivor, provided a rationale for why finding meaning in suffering is helpful: In Man’s Search for Meaning, he wrote: “In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.” And again, “Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.”

For Frankl, finding meaning in life is critical to mental health. The psychologist’s job is not to help their clients find meaning rather than make them feel happy. Finding meaning would help them grow in resilience to survive and thrive.

He was critical of the American fixation with happiness. The goal of psychotherapy was to help people act responsibly in addressing the challenges that inevitably arise in life. Freedom without responsibility deteriorates, fostering an arbitrary existence. This emphasis on responsibility went against the stream of reducing individual persons to merely victims of nature or nature’s effects. “Calling for a re-humanization of psychotherapy, he emphasized the importance of reconnecting people with personal responsibility in order to overcome feelings of meaninglessness and despair.” (Refer here for the quote and a good overview of Frankl’s work).

I have found one quote in particular from Frankl’s classic work, Man’s Search for Meaning, especially helpful: “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” This classic statement from Frankl’s work has helped me cope and find hope in dealing with the ongoing suffering and trauma resulting from my son Christopher’s catastrophic brain injury and its aftermath.

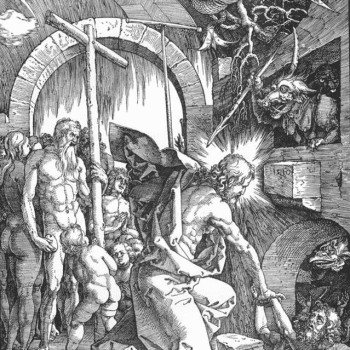

Innocent Suffering, Victory amid Victimization

My Christian faith and daily Bible readings have also helped me gain strength and a sense of purpose amid incredible trials in life. The New Testament presents Jesus and his community as resilient and creative amid great challenges to their faith. What I find most striking is how Jesus provides meaning amid horrific suffering. Some in the Christian community have presented Jesus as an innocent victim, who though victimized, did not victimize others. He atoned for our sin amid great travail and trauma so that we might experience healing. (Still, it is important to note that Jesus did not die on Yom Kippur, but during Passover.)

How can any people, or an individual person, find meaning and live victoriously amid incredible suffering and trauma? How might we maintain innocence and not participate in the ongoing cycle of victimization in our world today? This is not simply a question I ask in relation to the Jewish people and their faith tradition, but also in relation to Christians, Muslims, and people of any spiritual path, or no religious tradition whatsoever. In what follows, I will highlight a Christian perspective for how we might choose to find meaning and respond.

Charles Taylor: Violence, Vulnerability, and Transformative Meaning

Charles Taylor reflects on Jesus’ atoning work in A Secular Age. He offers an alternative to the view that features divine violence and frames suffering as divine, which involves “punishment and pedagogy” (See A Secular Age, 654):

We could start somewhere quite different, see suffering and destruction as often themselves devoid of meaning, and see the self-giving of Christ to suffering as a new initiative by God, whereby suffering repairs the breach between God and humans, and thus has not a retrospective or already established, but a transformative meaning.

We start with the fact of human resistance to God, closure towards God who could heal the consequences of this resistance, which we call sin. This is the first mystery. God’s initiative is to enter, in full vulnerability, the heart of the resistance, to be among humans, offering participation in the divine life. The nature of the resistance is that this offer arouses even more violent opposition, not a divine violence, more a counter-divine one.

Now Christ’s reaction to the resistance was to offer no counter-resistance, but to continue loving and offering. This love can go to the very heart of things, and open a road even for the resisters. This is the second mystery. Through this loving submission, violence is turned around, and instead of breeding counter-violence in an endless spiral, can be transformed. A path is opened of non-power, limitless self-giving, full action, and infinite openness. (A Secular Age, 654)

Further to Taylor’s reflection, I have often found Jesus’ actions following his resurrection from the dead quite striking and even counter-intuitive. Rather than seeking to get even, he makes whole. He does not lead his disciples to attack those who have done him wrong, but rather, he forgave them and asked God to do so, too. (See Luke 23:34; NIV)

Jesus’ Peace: Not Getting Even, But Making Whole

In the canonical gospels, we find the resurrected Jesus appearing and greeting his followers with the words, “Peace be with you!” (See John 21:19-23; NIV) He walks with two other disciples on the Road to Emmaus and later breaks bread with them (Luke 24:13-35). On another occasion, he instructed the disciples where to catch fish and prepared a meal for them. (21:1-14) He was/is a person of peace and hospitality, as my colleague Suzanne Smith remarked in reflecting on these biblical texts on the resurrection. Again, his aim is not to get even, but to make whole.

If this is the case for Jesus, in view of him and in participation with him, how shall we respond? Will we rise from the tomb with him and “enter, in full vulnerability,” as Taylor reasons, “the heart of resistance” among our fellow humans? Will we also enter, not to react and seek revenge, but open ourselves up to the power of a cruciform and risen life, which as Taylor reasons involves “non-power, limitless self-giving, full action, and infinite openness”?

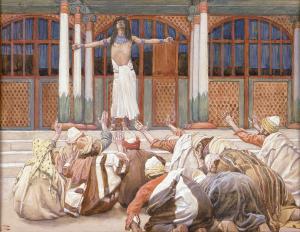

Joseph and Us: Reaction to Evil or Pro-action for Good?

It is not only freedom without responsibility that leads to an arbitrary existence. So, too, does the unending cycle of violence in our world today. Jesus calls us to enter the cycle of transformative meaning whereby we do not react, but proact. Rather than see ourselves as predetermined to play the victim and give up or get even, merely reacting in kind to what others have done to us. Jesus offers us another way, the path of vulnerability and a counter to the use of violence.

The biblical character Joseph was a type of Christ. He did not permit his victimizing life circumstances including his brothers’ selling him into slavery and later imprisonment to control him. Rather than be reactive, like Jesus, he was proactive in his relationships with those who harmed him. Rather than get even, he made whole. Joseph found meaning in his trials and reversed them to bring about a much greater good. To quote Joseph’s words uttered millennia ago to his brothers who had done him great harm, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives.” (Genesis 50:20; NIV)

It is not enough for me to quote these words. We must live them, as I pray these words over my son’s person and our future daily. I pray in earnest that our lives will count for a far greater good than the evils we have endured and that such good will lead to the liberation of many. Transformative meaning in the face of suffering and victimizing experiences gives rise to resilient hope and victorious living.