Several days ago, Real Time host Bill Maher blasted the uproar over “Chinese Virus” as “PC.” His outburst won him praise across the political aisle from Republican Senator Ted Cruz. Maher asserted,

So when someone says, “What if people hear Chinese Virus and blame China?” the answer is, “We should blame China.” Not Chinese-Americans, but we can’t stop telling the truth because racists get the wrong idea. There’s always going to be idiots out there who want to indulge their prejudices, but this is an emergency! Don’t we have bigger tainted fish to fry?

The same article in Fox News claimed that Maher “mocked the complainers, listing several other illnesses that are named after their locations of origin — such as the West Nile virus, Spanish flu and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).”

Maher, the former host of Politically Incorrect, may be the one who is politically correct, or at least historically incorrect. We will focus on the historical backdrop to the terminology “Spanish flu.”

Contrary to the assumption bound up with the name, PBS claims that the first known case was found to be in Kansas, not Spain: “Some, looking for a point of origin of the so-called Spanish influenza that would eventually take the lives of 600,000 Americans, point to that day in Kansas.”

It is also worth noting here that the Spanish referred to the contagion as the “French flu.” According to an article in Clinical Infectious Diseases published by Oxford University Press,

Some observers suggested that the epidemic could have been spread from France because of the heavy railroad traffic of unskilled Spanish and Portuguese workers to and from France who provided temporary replacement for the shortage of young French workers engaged in the war… Aside from a historical rivalry between France and Spain, this is the likely reason why, in Spain, the influenza was also known as the French flu.

The same article refers to a 2005 study that suggests that the origin of the Spanish flu may have been New York City. If so, could Americans ever be politically incorrect enough to refer to it as the “Yankee flu”? Here’s the abstract for that 2005 article in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States of America in which this point on the possible U.S. origin of the flu is made:

The 1918 “Spanish flu” was the fastest spreading and most deadly influenza pandemic in recorded history. Hypotheses of its origin have been based on a limited collection of case and outbreak reports from before its recognized European emergence in the summer of 1918. These anecdotal accounts, however, remain insufficient for determining the early diffusion and impact of the pandemic virus. Using routinely collected monthly age-stratified mortality data, we show that an unmistakable shift in the age distribution of epidemic deaths occurred during the 1917/1918 influenza season in New York City. The timing, magnitude, and age distribution of this mortality shift provide strong evidence that an early wave of the pandemic virus was present in New York City during February-April 1918.

As a Time article makes clear, prejudice, ethnocentrism and political agendas often if not always come into play when pointing fingers at a given people or nation:

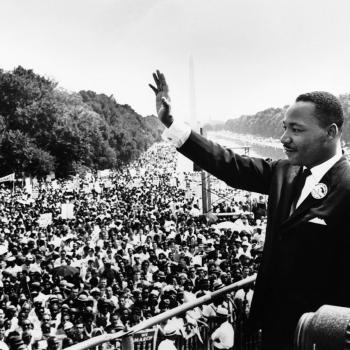

The name “Spanish flu” may have also reinforced a conflation between immigrants and disease at a time when white Americans descended from northern Europe held strong biases against immigrants from China and parts of eastern and southern Europe, including Spain. Just a couple of years before the 1918 flu outbreak, Italian immigrants on the East Coast were blamed for a polio outbreak, though in fact there was no evidence of an outbreak either in Italy or at Ellis Island. And for decades, white Americans associated Chinese immigration with a host of diseases, and used public health as an excuse to discriminate against them.

It is important to note here that American bias against the Chinese dates back at least to the documentation known as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which restricted immigration.

One of the most fatal mistakes in fighting a contagion is blaming other countries or diverse people groups for diseases. It is often based on misleading information involving prejudice and political agendas. I doubt those of us who are of northern European descent, or who are American, would take kindly to language like the “Yankee virus,” the “English virus” or “German virus” ever being used. We should put ourselves in others’ shoes. Moreover, given that the Coronavirus is now global, we really are in everyone’s shoes—even with the physical or social distancing. So, let’s simply refer to SARS-CoV-2 as the human virus or Coronavirus.

President Trump said back in March that he would stop using language like “Chinese virus.” Still, he and his colleagues have continued to point the finger at China. An article in Reuters on Saturday claimed: “Washington and Beijing have repeatedly sparred in public over the virus. Trump initially lavished praise on China and his counterpart Xi Jinping for their response. But he and other senior officials have also referred to it as the ‘Chinese virus’ and in recent days have ramped up their rhetoric.” It has been suggested that Republicans will seize on opportunities to blame the Chinese in that it “may be the best way to salvage a difficult election.”

Mistaken or calculated judgments like these divert our attention from actually combating the disease’s spread. Here it is worth pointing out that the Director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention has rejected such labels and associations with China. Such name-calling or finger-pointing between the U.S. and China has a negative impact on diplomacy and collaboration between the two countries. We must concern ourselves with deescalating such rhetoric, especially since the war with words between America and China helps nobody in fighting the virus. It’s a waste of energy and only puts others on the defensive. Instead of fighting the virus, we end up fighting one another. In the case of the U.S. and China, it might actually lead to war. They are not the only parties, though. U.S. adversaries are making the most of the current pandemic in their efforts to undermine and weaken the U.S. They need to lay down their arms as well and join in the fight against human well-being everywhere, including their own. Still, two or three of four wrongs of name-calling and undermining activity don’t make a right. The U.S. should lead the way in pursuing life-saving solutions.

Maher asks whether we don’t have “bigger tainted fish to fry” than getting caught up over language like “Chinese virus.” No, we don’t, in that such finger pointing detracts us from addressing the real problem, as noted above. Moreover, such prejudicial and mistaken language harms others. Just as Maher is incorrect historically about the Spanish virus, he is incorrect on the negative import of such language as “Chinese virus.” While Maher acknowledges that some people will use language like the “Chinese virus” to “indulge their prejudices,” why indulge them by stoking the fire of hatred, if you know such language incites further hate and harm? Deescalate rather than escalate. Such escalating indulgence causes great harm to the well-being of Chinese Americans and Asians generally (Refer here, here, and here for accounts of the danger and harm). Yes, fighting the Coronavirus is an “emergency,” as Maher reasons. So, too, is the need to fight prejudice with facts and empathy for the other, whoever the other may be. Fighting the disease and prejudice are bound up together.

We all tend to point the finger at the other, whoever the other may be. While it might make us feel better to blame someone not close to us and gives us a sense of immediate control in a crisis, it only leads to more harm. Pointing fingers at one another won’t help us resolve a global pandemic. Locking arms will (while practicing physical distancing!).

Rather than attaching a place or people to the Coronavirus, which knows no boundaries and is no respecter of ethnicity, skin color, sex, or age, let’s simply call this disease the Coronavirus. Let’s join others in calling out such divisive language (refer here to the Asian American Christian Collaborative), stand with those whom such language harms rather than stand aside, and get to work on frying the fish of diplomacy for the sake of global public health until the pandemic goes away.