How many spider webs have you seen? Do you find a beautiful symmetry in each design? I don’t find such symmetry in every spider web I see. Some are asymmetrical. Some are exceptionally messy. Now, in light of what we said of Jonathan Edwards’s fascination with spiders (refer here to the first part of this mini-series by the same title), some might consider his theology the equivalent of an asymmetrical spider web. Why is that?

Take for example Edwards’s sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Edwards describes an angry God dangling the sinner over the flames of hell like a spider over a blazing fire:

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight; you are ten thousand times so abominable in his eyes as the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours. You have offended him infinitely more than ever a stubborn rebel did his prince: and yet ’tis nothing but his hand that holds you from falling into the fire every moment; ’tis to be ascribed to nothing else, that you did not go to hell the last night; that you was suffered to awake again in this world, after you closed your eyes to sleep: and there is no other reason to be given why you have not dropped into hell since you arose in the morning, but that God’s hand has held you up; there is no other reason to be given why you han’t gone to hell since you have sat here in the house of God, provoking his pure eyes by your sinful wicked manner of attending his solemn worship: yea, there is nothing else that is to be given as a reason why you don’t this very moment drop down into hell.[1]

Based on this sermon, you might think Edwards was morbid, fixated on judgment and hell—a real pessimist. If true, Edwards’s literary spider web, which he spun, would lack any sense of hope, optimism, and beauty, and ultimately, aesthetic wholeness. Now, depending on who you ask,[2] that would be a mistaken assessment, and not simply because Edwards loved symmetry. Besides noting Edwards’s love of beauty and proportion, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” does not reveal the totality of Edwards’s sermonic repertoire. The editors of A Jonathan Edwards Reader assert,

As important as Sinners is…it cannot stand alone. Enveloping it is a cosmic optimism so inclusive that it binds individuals and planets into a universe of ultimate judgment and redemption. Even in Sinners, the reader discovers that all is not lost. The pessimism of sin and an angry God is overcome by the comforting hope of salvation through a triumphant, loving Savior. Whenever Edwards preached terror, it was part of a larger campaign to turn sinners from their disastrous path and to the rightful object of their affections, Jesus Christ.[3]

Moreover, the editors refer their readers to A Divine and Supernatural Light, which presents God’s love and grace in glorious terms. This particular work addresses the individual. Edwards’s publication, A History of Redemption, provides a cosmic vision of the redemption from a Trinitarian perspective.[4]

I was thinking of the apparent quest for symmetry in Edwards’s theology and sermons as I looked back on OMSC’s Jonathan Edwards tour this past winter, and as I have been pondering more recently Edwards’s aesthetic imagination. Our guide (Jon Hinkson of the Rivendell Institute at Yale University) spoke on the theme of the “pervasiveness of death” at one point on the tour. He noted how “much of Puritan instruction was designed to show how precarious life is.” Parents instructed their children that sleep is itself a type of death and taught their little ones this prayer: “This day is past, but tell me who can say, That I shall surely live another day.” The concern was more than imagined. Life in colonial America was exceptionally precarious. Our guide also quoted, “Nothing is more certain than death. Take no delay in the great work of preparing for death.” He shared that during Edwards’s senior year at Yale, he became deathly sick. Edwards painfully sensed that he was not prepared to meet his maker, remarking that the experience “shook me over the pit of hell.”

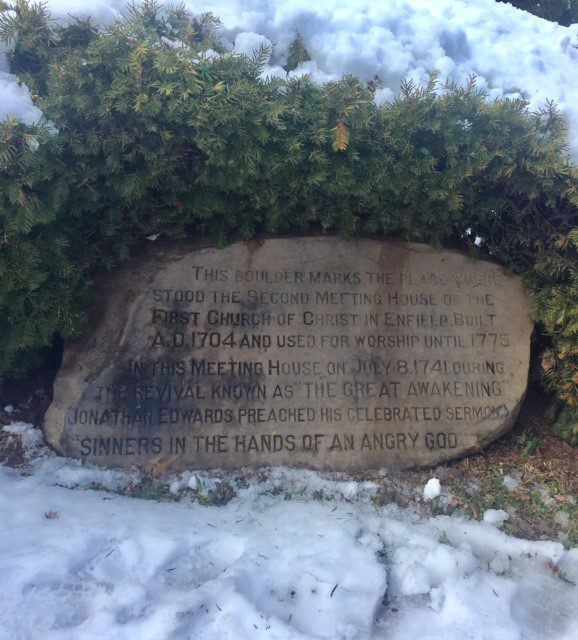

No doubt, the constant, close proximity of death to life for the very young to the very old, and Edwards’s own early encounter with the impending threat of death, shaped Edwards’s sermon, as well as his audience’s response. I got a taste of what these early Americans experienced as our narrator took us from a graveyard to the stone that marks the site (shown above) where Edwards preached this famous sermon during “The Great Awakening.”

One would have thought the imagery of the sermon, including God dangling the sinner over hell like a spider over a flame, was enough to warm my body as we stood in the snow as a strong wind hit our backs. However, perhaps I am just too cold-hearted, which is what Edwards feared for this congregation to whom he spoke as a guest preacher on July 8, 1741 (not 1941, as originally printed in this post!–thank you for the keen eye, Salvatore Anthony Luiso) in Enfield, MA. Theologians will debate the most effective way to awaken and warm souls—to move from the fear of God to the love of God, as Edwards appeared to do here, or from the love of God to the fear of God, as Karl Barth sought to do. Regardless what one makes of Edwards’s methodology in this sermon, and how it fits into his larger body of writings, one should not question his motive: to help his audience prepare to meet God so that they may not be ashamed and dismayed on the day of the divine visitation and the judgment to come. As Hebrews 9:27 declares, no one will escape mortality. All will have to give an account before God for our lives here below: “…it is appointed for mortals to die once, and after that the judgment” (Hebrews 9:27; NRSV).

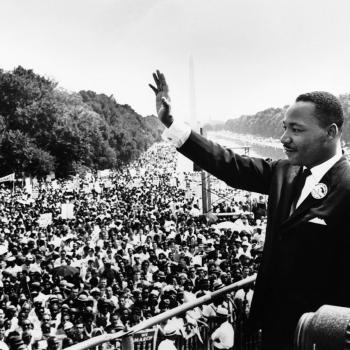

Perhaps Edwards’s theology lacked aesthetic wholeness, but one cannot accuse him of falling for naïve optimism that fails to see the lesser angels of our nature’s advance. Nor can one accuse Edwards of falling prey to morbid pessimism that never looks for the light which will lead us out of the darkness of despair. The Niebuhrs were drawn to Edwards’s bridling of the former tendency in our modern world,[5] while Martin Luther King, Jr. likely would have commended him for holding in check the latter tendency as well as the former.

Which tendency do you and I struggle most to overcome—naïve optimism or morbid pessimism? If we are not careful and do not tend to the state of our souls, we will get caught and trapped in the asymmetrical and messy spider web of our own making unto our undoing.

_______________

[1]Jonathan Edwards, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” in A Jonathan Edwards Reader, ed. John E. Smith, Harry S. Stout, and Kenneth P. Minkema (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), pages 97-98.

[2]Consider Amy Plantinga Pauw’s discussion of Edwards’s theological program: “Edwards’s conception of God’s trinitarian union with creation could have funded a deep and expansive theology of cosmic redemption that embraced the groanings of all creation for liberation from its bondage to decay.” Pauw goes on to write that, “Yet it did not, and we find instead a drastic truncation of the moral and theological significance of the creaturely world within Edwards’s thought. Instead of a cosmic redemption, there is a cosmic holocaust: the earth created by God is annihilated in a paroxysm of apocalyptic violence, and the vast majority of God’s creatures are eternally bereft of the communications of God’s goodness and love that were God’s end in creation. Edwards’s treatment of sin, exacerbated by the idealist and rationalist impulses of his theology, is largely to blame for the failures of his doctrine of creation.” Lastly, “In Edwards’s theology, human and angelic sin strikes a blow from which God’s gracious end in creating the world never recovers: creaturely sin occasions the eternal destruction of the earth and most of its creatures.” Amy Plantinga Pauw, The Supreme Harmony of All: The Trinitarian Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), page 132. Later, Pauw writes of Edwards’s “cobbled Trinitarianism” that does not evidence the kind of coherence found in systematic theology in the modern period. His pastoral context where biblical and theological reflection was bound up with the immediate needs of congregants was a factor in this eclecticism. Pauw also reasons that the way in which Edwards drew upon psychological and social Trinitarian models in the development of his theology also led to a cobbled quality to his thought (pages 185-187).

[3]“Editor’s Introduction,” in A Jonathan Edwards Reader, ed. John E. Smith, Harry S. Stout, and Kenneth P. Minkema (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), page xviii.

[4]“Editor’s Introduction,” in Edwards Reader, page xix.

[5]“Editor’s Introduction,” in Edwards Reader, page xvii-xviii.