It is off-limits—illegal—in some circles to look at the faces and listen to the personal stories of undocumented workers. Many in these circles fear that if you move it beyond faceless, nameless policies, you will make exception after exception. On this view, the claim is made that you should never base laws on exceptions, so you ignore the exceptions. But the exceptions have faces and names, wives and husbands, children and parents, fears and hopes, just like we do.

Jesus’ answer to the question—“Who is my neighbor?” (in Luke 10)—is not intended for generic policy position papers, but for each of the people who cross our paths. In Letters and Papers from Prison, Dietrich Bonhoeffer writes about monumental doctrinal themes like transcendence and the grand omnis of orthodox theology. Regarding relationship with God and our framing of these categories, he writes: “Our relation to God is not a ‘religious’ relationship to the highest, most powerful, and best Being imaginable—that is not authentic transcendence—but our relation to God is a new life in ‘existence for others’, through participation in the being of Jesus. The transcendental is not infinite and unattainable tasks, but the neighbour who is within reach in any given situation…” (Letters and Papers from Prison, Touchstone edition, 1997, p. 381).

Speaking of “the neighbour who is within reach in any given situation,” Jesus does not tolerate the religious scholar’s attempt to justify himself in Luke 10 by raising the question, “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29) Jesus’ answer suggests that the question is off-limits to Jesus, even illegal in view of the scholar’s intent to distance himself from taking responsibility for his neighbor. Jesus then tells the scholar who had come to test him on the essence of the law and its requirements for gaining eternal life (Luke 10:25) a story in which religious leaders like himself failed to care for their neighbor, who was within their reach in a given moment and situation. While it may have been ceremonially illegal for the religious leaders in the story narrated in Luke 10 to care for the man beaten and robbed and left for dead, Jesus does not let them off the hook. Only the seemingly illegal and immoral Samaritan fulfilled the law by acting mercifully in the moment (Luke 10:30-35).

Speaking of “the neighbour who is within reach in any given situation,” Jesus does not tolerate the religious scholar’s attempt to justify himself in Luke 10 by raising the question, “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29) Jesus’ answer suggests that the question is off-limits to Jesus, even illegal in view of the scholar’s intent to distance himself from taking responsibility for his neighbor. Jesus then tells the scholar who had come to test him on the essence of the law and its requirements for gaining eternal life (Luke 10:25) a story in which religious leaders like himself failed to care for their neighbor, who was within their reach in a given moment and situation. While it may have been ceremonially illegal for the religious leaders in the story narrated in Luke 10 to care for the man beaten and robbed and left for dead, Jesus does not let them off the hook. Only the seemingly illegal and immoral Samaritan fulfilled the law by acting mercifully in the moment (Luke 10:30-35).

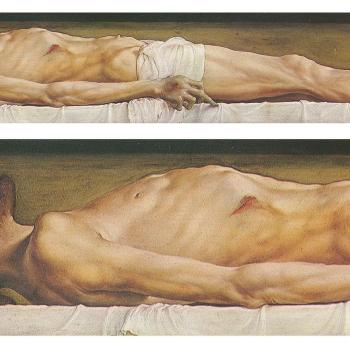

We can live the entirety of our lives according to transcendental and legal policies that leave people dying on the road, but fail to care for the transcendental reality of the illegal person lying there before us. Such systems of justice will not judge us, but the transcendent Jesus who is dying on the road as the discounted exception to our rule will.

This piece is cross-posted at The Institute for the Theology of Culture: New Wine, New Wineskins and The Christian Post.