A couple of years ago, I wrote an article for the Federalist claiming that most American Christians are heretics. I grounded this bold charge on a previous State of Theology survey commissioned by Ligonier Ministries and conducted by LifeWay Research. In the survey, a significant proportion—in some cases a majority—of self-identified evangelicals fessed up to beliefs that run afoul of the Nicene and Chalcedonian formulas, Christian tradition, or Scripture. I think I was on the right track with my gloomy assessment, and the 2018 State of Theology survey only reinforces the original evidence. If anything, the results look worse. But I want to revise my previous conclusion that most Christians are heretics, because heresy means obstinate error, and most Christians aren’t in obstinate error. They just don’t speak the language of Christianity fluently anymore. Almost no one does.

In Ligonier’s latest survey, 52 percent of evangelicals agreed with the statement that everyone sins a little, but most people are good by nature. 51 percent affirmed that God accepts the worship of all religions (up slightly from 2016), and 78 percent think Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God, up from 71 percent a couple of years ago. For those taking notes, this position is the main assertion of Arianism, a heresy condemned by the first ecumenical church council in A.D. 325.

Accidental heresy also characterizes our society more broadly. Ligonier found that almost 70 percent of Americans disagree with the statement “even the smallest sin deserves eternal damnation,” which is a historic Christian doctrine, and a fair summary of James 2:10. Similarly, most agree that worshiping alone or with family at home is a valid replacement for regular church attendance, signaling how radically we have privatized religion. And 60 percent of Americans (along with 30 percent of evangelicals) think religious belief is “a matter of personal opinion,” and is “not objectively true.”

Why do none of these unorthodox survey answers fit the technical definition of heresy? Because almost no one who gives such answers today does so as a matter of conviction. Some may be willing to cling to their false beliefs, if confronted. But I suspect the vast majority both inside and outside the church stumble into these errors, largely because no one regularly talks with them about spiritual truths. Increasingly, we don’t even have the vocabulary to discuss God or morality even on those occasions when the fancy strikes us.

Why do none of these unorthodox survey answers fit the technical definition of heresy? Because almost no one who gives such answers today does so as a matter of conviction. Some may be willing to cling to their false beliefs, if confronted. But I suspect the vast majority both inside and outside the church stumble into these errors, largely because no one regularly talks with them about spiritual truths. Increasingly, we don’t even have the vocabulary to discuss God or morality even on those occasions when the fancy strikes us.

Writing at the New York Times, Jonathan Merritt points out that it’s getting harder in our secular society to express ideas about God, faith, or traditional morality, because we almost never use the words past generations bequeathed us for the task. This atrophy of religious language is empirically verifiable. Merritt cites a study by the Barna Group that found over a fifth of Americans haven’t had a spiritual conversation in the last year. Six in ten admitted that they only have such conversations on rare occasions—“rare” being defined as once or twice to several times a year! A paltry seven percent indicated they talk about spiritual issues on a regular basis. And even among practicing Christians, just 13 percent have spiritual discussions once a week or more.

Because of this, religious terms like “gospel,” “salvation,” “sin,” and “grace”—“God-talk” as Merritt dubs it—are disappearing from our language. To get specific, the Journal of Positive Psychology published an analysis of how frequently fifty moral terms appeared in a large corpus of American books over the course of the twentieth century. Virtue-words like “love,” “patience,” “gentleness,” and “faithfulness”—once commonplace in publications of all sorts—are now on the linguistic equivalent of the endangered species list. Merritt says use of “humility words” like “modesty” fell by 52 percent. “Kindness,” plummeted by 56 percent. “Thankfulness” and similar words have declined by 49 percent.

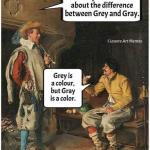

All of this points to the conclusion that for Americans of all stripes who express heterodox opinions on theology surveys, the problem isn’t persistent false beliefs about spiritual things. The problem is a total unfamiliarity with such things. For a huge and growing chunk of our society, both nominally religious and otherwise, Christian theology has become a foreign language. When asked about God, salvation, Scripture, and morality, the very words of the questions sound to them like the foremen at the Tower of Babel. How can they answer the questions accurately? They don’t even understand them.

This is why I now suspect that as an answer to this problem, “theological education,” while certainly an essential part of the solution, is putting the cart before the horse. As Puddleglum quipped when Jill Pole said their little band had to start by finding a ruined city of giants, (I am on a Narnia “Silver Chair” kick lately), “Got to start by finding it, have we? Not allowed to start by looking for it, I suppose?” Before we can learn how to talk about God again, we have to—you know—start talking about God, again.

This will mean, for one thing, deliberately transgressing secular plausibility structures, as the kids these days say—those words the customs that allow us to go to work, school, and even church, all week, for weeks on end, without seriously discussing God, the afterlife, or religion with anyone we meet. Does it feel awkward striking up a conversation with a stranger on the subway reading a Deepak Chopra book? Push back against that awkwardness. That’s the spirit of the age resisting you. Do you talk about sports with that coworker on an almost daily basis but neglect entirely to mention your faith in Jesus—ostensibly the most important part of your life? Mention it. Break out of your comfort zone. Do you tell yourself you’ll eventually get back with your accountability partner about your newly rekindled porn habit? Pick up the phone and do it now. Use old words like “sin,” “repentance,” and “forgiveness.”

Talking about God again will also require a lot of humility, for the simple reason that we are very bad at it. When you’re learning a new language, you don’t make any progress by refusing to open your mouth for fear of making mistakes. You start trying to speak words and sentences, knowing you sound like a nincompoop to native-speakers. Don’t worry about this. But don’t hold on to your accidental heresies, either. Be very open to correction, which (providentially), we have the tools to offer. Our ancestors bequeathed us more than just a spiritual vocabulary. They also left us spiritual training wheels—creeds, confessions, and catechisms—standards of faith and theology produced by generations of debate and Scriptural study. These are our dictionaries and primers for God-talk.

Most Americans and American Christians aren’t heretics, at least not technically. In some ways, the true state of our theology is both more sobering and challenging. So many of us get questions about God wrong for the same reason we get questions in a foreign language wrong. We don’t understand the words. We rarely hear them, if ever. So, if we want to teach people the truths of the faith, the first step is demonstrating that faith is still worth talking about, and that Christian theology is not a dead language.