Every Wednesday during Lent, I’m going to explore an alternatives to the penal substitutionary understanding of the atonement, the dominant theory of the atonement in my part of the (theological and geographical) world. You can read all of the posts, and my past posts on this topic, here. I’ve got an ebook on the subject as well.

In 1930, a relatively unknown Swedish bishop and theologian revived an understanding of the atonement that had largely been forgotten for 1,000 years. Gustaf Aulén’s book, Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Atonement was translated into English the next year, and it’s stayed in print ever since.

The Christus Victor model, Aulén argues, was the predominant theory for the first millennium of the church, and it was held by the majority of the church fathers whom we still revere. Along came Anselm and changed the game — for reasons I’ve written about before and will discuss in an upcoming post — and CV was relegated to history’s rubbish bin. Until Aulén.

Today, CV has had something of a resurgence. 😉 That’s been led by Greg Boyd — who’s personal brand was called, until recently, Christus Victor Ministries — and others.

CV falls under a broader umbrella called the Ransom Theory. In this understanding, the original sin of Adam and Eve placed all of humanity under subjugation to Satan. Christ, the second person of the Trinity, came to Earth and died, giving his life as a ransom for many.

At this point, CV may sound like the penal substitution model that many of us grew up with. But that’s where Aulén said we’re wrong. The early church did not understand the death of Christ as paying a penalty in some transactional sense that only God’s son could pay. The crucifixion is not, in that sense, cosmically necessary to reconcile God and humanity.

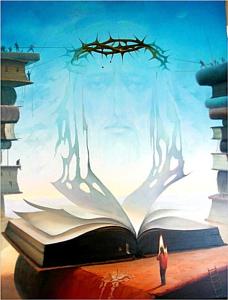

Instead, Christ’s death is God’s victory over sin and death. God conquers death by fully entering into it. God conquers Satan by using the very means employed by the Evil One.

Thus, the crucifixion is not a necessary transaction to appease a wrathful and justice-demanding deity, but an act of divine love.

God entered fully into the bondage of death, turned it inside out by making it a moment of victory, and thereby liberates humanity to live lives of love without the fear of death.

It’s a beautiful thing, the crucifixion, in this view. And, for those of us who are robustly trinitarian, it maintains an egalitarian view of the Trinity — one in which the Son and Spirit are not junior partners in the atonement.