Confirmation bias is a pervasive challenge. I am victim to it; you are victim to it.

I have been embroiled in many arguments about racial equality in many different places. I was beset on Twitter by a number of people after I took issue with someone who posted this:

There is no pattern of racist White cops killing Black people disproportionately or without consequence.

That's a dangerous myth you've been duped into believing pic.twitter.com/4BZvc1FbKZ

— Gypsytits (@Gypsytits1) June 6, 2020

I simply pointed out that his was a graph that had nothing to do with police killings – it showed something completely different. That he should probably delete his tweet. I provided him with a couple of more relevant graphs.

I was then confronted with an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal by Heather MacDonald, something I have seen all over the internet, linked by white right-wingers pushing back at the BLM narrative: “The Myth of Systemic Police Racism”. I have seen people fawning over it, thinking it blows the claim of systemic racism out of the water. It’s behind a paywall but you can see it here. I want to take issue with this piece because, well, somebody has to.

Let’s have a look at some of the claims. Obviously, it is worth noting the source: someone with a book to sell about the topic (The War on Cops) writing in a right-wing newspaper. Be aware of confirmation bias, including mine. Let me know about mine and if I get things wrong in the comments below. I will produce some of its lines here and respond interlinearly. I don’t have time or space to deal with it all. But let’s start with the first line:

George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis has revived the Obama-era narrative that law enforcement is endemically racist.

This is a case of poisoning the well with mention of Obama – this will serve to prime the WSJ readership, but this has been endemic for long before 2008. The fact that she calls him “Mr. Obama” later in this paragraph is pretty much all the evidence you need to where this is going. Journalism done bad.

However sickening the video of Floyd’s arrest, it isn’t representative of the 375 million annual contacts that police officers have with civilians. A solid body of evidence finds no structural bias in the criminal-justice system with regard to arrests, prosecution or sentencing. Crime and suspect behavior, not race, determine most police actions.

This is the crux of the article and it will be interesting to see how she defends this position. Annual contacts is an interesting metric. What we really want to know is “How frequently is force used against a person when no threats were apparent?” and compare these across racial subgroups. She continues:

In 2019 police officers fatally shot 1,004 people, most of whom were armed or otherwise dangerous. African-Americans were about a quarter of those killed by cops last year (235), a ratio that has remained stable since 2015. That share of black victims is less than what the black crime rate would predict, since police shootings are a function of how often officers encounter armed and violent suspects. In 2018, the latest year for which such data have been published, African-Americans made up 53% of known homicide offenders in the U.S. and commit about 60% of robberies, though they are 13% of the population.

My initial retort is this, and it comes from a statistical analysis – some scholarly research – not just someone looking at headline data and assuming it is accurate and then giving it a prima facie sweep. This is from “An authentic discourse: Recentering race and racism as factors that contribute to police violence against unarmed Black or African American men” by Hadden et al.:

This study explores the relationship between race, racism, and attitudes toward police violence against adult males. Study participants comprised a national sample (N = 1,974) of adult males and females (M = 48 years) who completed the 2012 General Social Survey (GSS). Secondary data analysis of surveys administered in-person or on the telephone by trained GSS interviewers indicated that race is a key predictor of police violence against adult males [χ2 (7) = 85.710, p < .0001], even after controlling for sex, education, income, and age. Study findings also revealed that attitudes supportive of police violence are associated with negative cultural images of Blacks or African Americans. Participants who approved of police violence against males attributed disparities in employment, income, and housing between Blacks or African Americans and Whites to a lack of motivation and ability to learn, rather than to racial discrimination and lack of education incurred through poverty. These findings challenge us as social work educators and practitioners to further explore the association between racism and police violence and to unmask the debilitating consequences of the presumed limitations of Blacks or African Americans.

This should be enough, really, but let’s delve further and start with looking at problems with data collection and police deaths. Part of the issue with police forces in the US is that they are controlled at state and county level, and recording data is a challenge, particularly when it is data that may make the police look bad. There are 18,000 police agencies in the US who are expected to voluntarily submit their data… Heck, The Guardian, a British newspaper, took it upon themselves in 2015-16 to build up a database of police killings because the States is so bad at it:

Why is this necessary?

The US government has no comprehensive record of the number of people killed by law enforcement. This lack of basic data has been glaring amid the protests, riots and worldwide debate set in motion by the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old, in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014.

Before stepping down as US attorney general in April 2015, Eric Holder described the prevailing situation on data collection as “unacceptable”.

The Guardian agrees with those analysts, campaign groups, activists and authorities who argue that such accounting is a prerequisite for an informed public discussion about the use of force by police.

How does the US government count killings by police now?The FBI runs a voluntary program through which law enforcement agencies may or may not choose to submit their annual count of “justifiable homicides”, which it defines as “the killing of a felon in the line of duty”.

This system is arguably less valuable than having no system at all: fluctuations in the number of agencies choosing to report figures, plus faulty reporting by agencies that do report, have resulted in partially informed news coverage pointing misleadingly to trends that may or may not exist.

“We lack the ability right now to comprehensively track the number of incidents. … Fixing this is an idea that we should all be able to unite behind.”

–Eric HolderBetween 2005 and 2012 just 1,100 police departments – a fraction of America’s 18,000 police agencies – reported a “justifiable homicide” to the FBI.

The FBI system counted 461 justifiable homicides by law enforcement in 2013, the latest year for which data is available. Crowdsourced counts found almost 300 additional fatalities during that year. The Counted, upon its launch on June 1, 2015, had already found close to that number of killings in just the first five months of 2015.

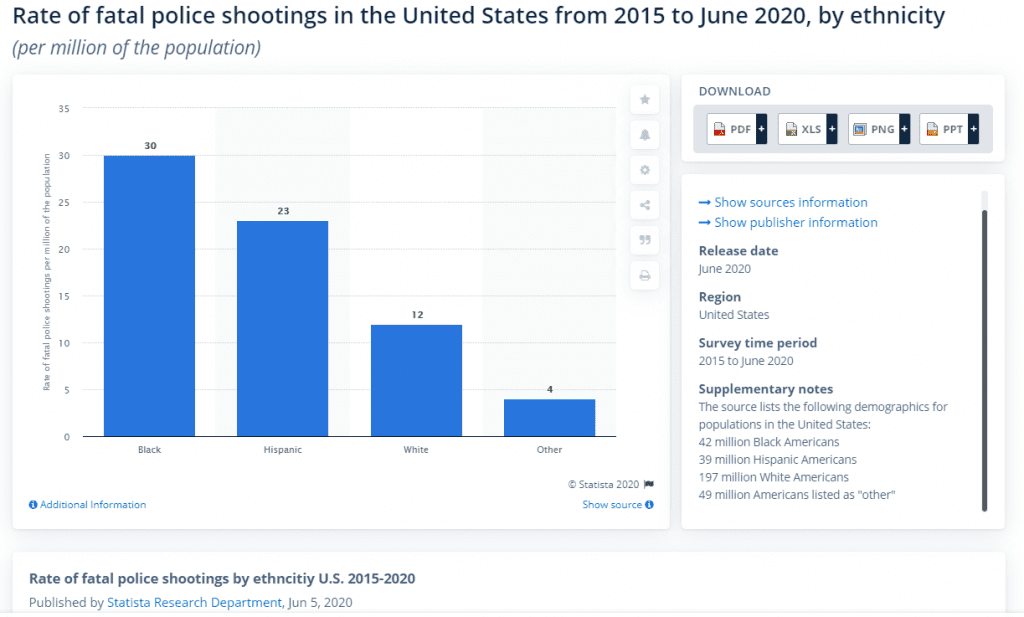

Indeed, as a result of this, the federal reporting program doubled the killings listed in 2016. MacDonald uses these Statista stats, but are they wholly accurate? Statista has this rate still almost three times higher for blacks than whites, where the source lists the following demographics for populations in the United States:

- 42 million Black Americans

- 39 million Hispanic Americans

- 197 million White Americans

- 49 million Americans listed as “other”

Either way, we know that the US police shoot and kill far more people than other comparable countries. Blacks do account for the larger proportion of violent crimes, this is true (predominantly intraracial for homicides). What we would need to know is in what context were these police shootings? Were they in the context of stopping armed robberies or homicides? And, given a same scenario, ceteris paribus, would a black person be more likely to be shot than a white person.

This data, unfortunately, does not have enough resolution.

More than this, though, we are often talking about non-gun related deaths. We already know that, if the police are violent to people, it is 2.8x more likely to end in death if the person is black. George Floyd had a knee put on his neck and Eric Garner was choked to death. Had this not been filmed, one wonders how the police would have recorded it. Not only this, but incidents do not always end in death. In Minneapolis, the heart of this, police use force against blacks at a rate of 7x that of whites. This is what Nature struggled with in “What the data say about police shootings” with the tagline “How do racial biases play into deadly encounters with the police? Researchers wrestle with incomplete data to reach answers.” They opine:

Those cases and others raised questions about the extent to which racial biases — either implicit associations or outright racism — contribute to the use of lethal force by the police across the United States. And yet there was no source of comprehensive information to investigate the issue. Five years later, newspapers, enterprising individuals and the federal government have launched ambitious data-collection projects to fill the gaps and improve transparency and accountability over how police officers exercise their right to use deadly force.

But this cuts both ways, of course. It is difficult to say that the police are systemically racist as well as defending them as MacDonald does. I would thoroughly recommend reading the CityLab article from 2019: “What New Research Says About Race and Police Shootings“.

It is also absolutely worth reading Chapter 5 by Kelly Gates (“Counted the Uncounted: What the Absence of Data”) in Police Killings Reveals”) in Digital Media and Democracratic Futures (2018). It is staggering (in terms of intentionality, scale and chronicity), given the voluminous data on crime, that this data is hitherto absent. I would love to quote the whole chapter, but… It discusses why such local, state and federal shortcomings has led to crowdsourcing days collection such as The Guardian’s The Counted. It did lead me to the article “What I’ve Learned from Two Years Collecting Data on Police Killings“:

The biggest thing I’ve taken away from this project is something I’ll never be able to prove, but I’m convinced to my core: The lack of such a database is intentional. No government—not the federal government, and not the thousands of municipalities that give their police forces license to use deadly force—wants you to know how many people it kills and why.

It’s the only conclusion that can be drawn from the evidence. What evidence? In attempting to collect this information, I was lied to and delayed by the FBI, even when I was only trying to find out the addresses of police departments to make public records requests. The government collects millions of bits of data annually about law enforcement in its Uniform Crime Report, but it doesn’t collect information about the most consequential act a law enforcer can do.

I’ve been lied to and delayed by state, county and local law enforcement agencies—almost every time. They’ve blatantly broken public records laws, and then thumbed their authoritarian noses at the temerity of a citizen asking for information that might embarrass the agency. And these are the people in charge of enforcing the law.

The second biggest thing I learned is that bad journalism colludes with police to hide this information. The primary reason for this is that police will cut off information to reporters who tell tales. And a reporter can’t work if he or she can’t talk to sources. It happened to me on almost every level as I advanced this year-long Fatal Encounters series through the News & Review. First they talk; then they stop, then they roadblock.

This is the big thing to take away from my analysis – the absence of data and why this might be. And one could even level at the system that any intentionality behind this might also be a result of systemic racism and bias.

Nature continues:

Although the databases are still imperfect, they make it clear that police officers’ use of lethal force is much more common than previously thought, and that it varies significantly across the country, including the two locations where Brown and Garner lost their lives. St Louis (of which Ferguson is a suburb) has one of the highest rates of police shooting civilians per capita in the United States, whereas New York City consistently has one of the lowest, according to one database. Deciphering what practices and policies drive such differences could identify opportunities to reduce the number of shootings and deaths for both civilians and police officers, scientists say….

In December 2014, spurred by unrest in the wake of Ferguson, then-US president, Barack Obama, created a task force to investigate policing practices. The group issued a report five months later, highlighting a need for “expanded research and data collection” (see go.nature.com/2kqoddk). The data historically collected by the federal government on fatal shootings were sorely lacking. Almost two years later, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) responded with a pilot project to create an online national database of fatal and non-fatal use of force by law-enforcement officers. The FBI director at the time, James Comey, called the lack of comprehensive national data “unacceptable” and “embarrassing”.

Wow. So full data collection started only this year. Headline being that the data used by MacDonald will be wrong. How wrong is hard to tell. For every one person killed by police, at least another two were shot at.

Here’s my take: there is too much police violence (easy for me to say, sitting in my comfort). This violence is likely to move along in-group/out-group lines. People = qua police are far more likely to shoot out-group males than in-group males due to empathy and intersubjectivity. This is simple psychology. The more representative the police is, the fairer the stats will be. It’s human nature.

Black and minority ethnicities are hugely under-represented in the police.

That should really be the crux of this whole debate. If police are human, and we want to control the outcomes of human behaviour, we need to think of other means outside of regulation of policing methods. And, of course, people are, but this movement is not quick enough.

As Nature continues:

Researchers have used various approaches to try to determine the best benchmarks for the data, such as looking at the arrest rates where the shootings occurred or factoring in the context of encounters that end in a shooting. Did the suspect have a weapon? Were officers or another civilian being threatened? In a 2017 study3, for example, Nix determined that black people fatally shot by the police were twice as likely as white people to be unarmed. Those findings align with many studies published since 2015 suggesting that racial biases do influence police shootings.

But there is conflicting data, and so Nature admit that this is about finding out an accurate encounter rate and this is elusive. Simply put, there is no way to answer “How frequently is force used against a person when no threats were apparent?” because the data isn’t there. This is a methodological problem that cannot be solved in a simple manner.

Essentially, this should be enough to deal with the rest of the article, but there are a few other quotes to look at, namely:

By contrast, a police officer is 18½ times more likely to be killed by a black male than an unarmed black male is to be killed by a police officer.

I’m not sure this is a meaningful stat, with no comparison between racial subgroups and it doesn’t explain why the unarmed black man does get shot. This says more to me about gun violence and gun deaths and the need for the US to think long and hard and openly about gun control.

Which it won’t, of course, not while the NRA bribe Republicans, and not while 2A advocates march around pretending to care about tyrannical governments when they don’t, really.

In fact, MacDonald’s whole next paragraph seems to be a lamentation of gun violence without any direct relevance to police systemic racism. It is essentially a form of whataboutery, though her claims make me angry, too. They require urgent attention and political action.

She proceeds to pick one 2015 piece of research that suits her conclusions but fails to mention the plethora of others that don’t. And this is the problem with very messy, decentralised data. There is something for everyone. When talking about systemic racism, we have a problem with the sheer number of systems, counties, states, regions, demographics, cities, rural areas we can be drawing on. This reference is an analysis by the Department of Justice Community Oriented Policing Services: essentially, an analysis on themselves. Call me a cynic, but… Indeed, this article, referenced earlier, goes to town on Philadelphia’s police violence data methods and statistics.

We can all pick localised studies, right?

These inconsistences are not explained by zip code data, which shows that these inconsistences remained true across all zip codes making up the city of Peoria. In addition, black people were more likely to be searched but less likely to have contraband on their person. And furthermore, when a black person was found with drugs, it was typically less than the average amount found on white citizens. This disparity hits black males the most between 20 to 40 years of age. This paper concludes by presenting recommendations to the Peoria Police Department and the public.

But here’s a really big problem for MacDonald. She claims:

The latest in a series of studies undercutting the claim of systemic police bias was published in August 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The researchers found that the more frequently officers encounter violent suspects from any given racial group, the greater the chance that a member of that group will be fatally shot by a police officer. There is “no significant evidence of antiblack disparity in the likelihood of being fatally shot by police,” they concluded.

What she failed to include or reference were the letters and rebuttals to PNAS as a direct result of this piece, including:

Despite the value of this much-needed research, its approach is mathematically incapable of supporting its central claims. In this letter, we clarify the gap between what Johnson et al.’s study asserts and what it actually estimates, as well as the implications of that difference for policymaking and future scholarship on race and policing.

And then it goes not o deconstruct the mathematics of the paper, concluding:

Johnson et al.’s (1) study describes attributes of fatal police shootings. While a contribution, these facts alone cannot inform the relative likelihood of White and non-White officers shooting racial minorities. Readers and policymakers should keep this important limitation in mind when considering this work.

A further corrective letter concerning this research with reference to other research (“Young unarmed nonsuicidal male victims of fatal use of force are 13 times more likely to be Black than White”) states:

A recent PNAS article reports “no evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities across [fatal] shootings” by police officers (ref. 1, p. 15877). This claim is based on the results of a regression model that suggested “a person fatally shot by police was 6.67 times less likely (odds ratio [OR] = 0.15 [0.09, 0.27]) to be Black than White” (ref. 1, p. 15880). The article also claims the results “do not depend on which predictors are used” (ref. 1, p. 15881). These claims are misleading because the reported results apply only to a subset of victims and do not control for the fact that we would expect a higher number of White victims simply because the majority of US citizens are White….The stark contrast between the published finding and our finding contradicts Johnson et al.’s (1) claims that their results hold across subgroups of victims. Contrary to this claim, their data are entirely consistent with the public perception that young male victims of fatal use of force are disproportionally Black. Importantly, neither the original finding nor our finding addresses the causes of racial disparities among victims of deadly use of force. Our results merely confirm other recent findings that racial disparities exist and that they are particularly large for young males (2).

That should be terminal for MacDonald’s case as this was really the only meaningful research she pulled on outside of here own dabbling with the Statista numbers. Searching “police systemic racism” in Google Scholar gives 77,400 results and is a good place to start.

Conclusion

What can we learn from this?

Well, if this person wrote a book called “The War on Cops”, I would really hope that her grasp of data, methodology and research publication is a damn sight better than it is in her short piece. It is understandable that right-wingers have jumped on this and fawned over it. It does present some important questions, for sure; the data is very messy and is probably not as clear-cut as many would like, and that applies to both sides. But looking at the mass of data on this across multiple fields, and knowing human cognitive psychology, you would be pretty brave to suggest that the police force, given the sorts of people who are often recruited to them, will not, to some trend, show systemic prejudice.

I am not having a go at the police here. Let this be stated categorically. I know a number of policemen personally in the UK (“some of my best friends are black”!), though they could be a world apart from their American counterparts. What I am saying is that the police are biased because they are human and we are all biased. It would be a miracle if they weren’t. Give them guns, and give the general public guns, and you see where this might go. I posit that there is systemic racism and bias in the police in the US because there is systemic racism and bias everywhere in the US (and elsewhere). Our parent’s generation still had segregation, for crying out loud. This shouldn’t be a “wow” scenario, but it also shouldn’t be buried under bad journalism and cognitive dissonance. This should be expected but not tolerated, explained but not justified.

Be honest, and be active.

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook:

You can also buy me a cuppa. Or buy some of my awesome ATP merchandise! Please… It justifies me continuing to do this!