I love this piece over The Daily Beast revisiting the life and legacy of Thomas Kinkade, the “Painter of Light.”

Kinkade’s fantastical paintings filled the homes of the wealthier Evangelical Christians where I obediently came for Bible study and fellowship when I was younger. They were ubiquitous as fish stickers on the back of the minivan, for those who could afford them, both an Evangelical dog-whistle and status symbol.

And yet the people I knew who spent thousands of dollars on Kinkade paintings in the 1980s and 90s were good people, people trying to live out their faith in the way they thought they were supposed to. Plus, I think, they genuinely liked the paintings.

I never cared for the paintings myself and often sneered at them, something I now regret. Sneering isn’t any better than mindlessly following a trend.

Thomas Kinkade died in 2012, after a dramatic cycle of alcoholism and a separation from the wife he referenced in every painting. He died as a Christian but also as a broken man.

I like this article because it gets into the complexity of faith and weakness, of art and commercialism, of painting the world as it is versus painting it as we wish it were.

Here is an intriguing detail about a dog and how he made his way into a light-filled frame:

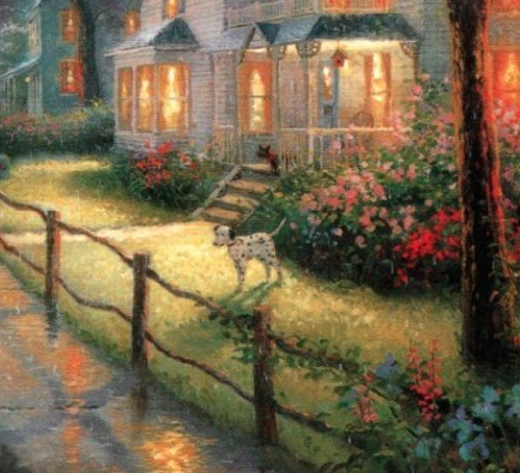

[Thomas Kinkade’s brother Patrick Kinkade] showed pieces by Rembrandt and Bierstadt followed by Kinkade’s works to trace the artistic influence, and he talked about the dog in Kinkade’s popular 1995 piece “Hometown Memories I: Walking to Church on a Rain Sunday Evening.”

That painting was based on the homes the brothers delivered papers to as children, and Patrick pointed to a cute dog in the foreground. While Thom was working on the piece, he called his brother and described the scene. “I’m painting Spotty,” he said.

Spotty had been a neighborhood menace. “That dog looks like a Dalmatian. It’s not. It’s half-Dalmatian, and half-Doberman,” Patrick explained, pointing at the piece in his PowerPoint. “Dalmatians are a little bit hyper. Dobermans are a little aggressive. Put em’ together, what do you get? Hyper-aggressive.”

“Why are you doing that?” Patrick had asked the painter. “We hated that dog.”

“To taunt you,” his brother replied. But in the painting, because this is a Thomas Kinkade piece, Spotty looks like a sweet little Dalmatian. “Thom was a romantic,” Patrick said.

So Kinkade was rewriting his own history, casting a warm glow on his own dark childhood. These are deep waters. Perhaps he painted illogical light to cover raving demons.

I don’t know much, but I know addiction is a powerful disease for believers and non-believers alike. I know that Evangelicals are not the only ones who feel they must present a mask of perfection to the world and keep the ickiness private.

Kinkade fascinates me because it’s all these things merged into a giant metaphor, a huge puzzle of faith and flaw. Idealized art – if it is indeed art – broken life, expectations, reality all mixed into a powerful brew.

The entire article is well worth a read.