Ah Woody Allen, the quintessential New Yorker, neurotic, self-focused, consumed with triviality of details.

Ah Woody Allen, the quintessential New Yorker, neurotic, self-focused, consumed with triviality of details.

So can he “get” the Eternal City, a place completely uninterested in the individual? A city infused with millennia, steeped in ancient humanity, the push and pull of empire and faith?

Apparently not, if his movie To Rome with Love, is any indication. (Click through for my review.)

Manhattan, he gets. That’s a given. He captured the magic and fantasy of Paris in Midnight in Paris. He can do Los Angeles and Barcelona and London.

But Rome?

It may be too much for him.

He populated his Rome with New Yorkers, some characters actual New Yorkers imported from the States and others a Roman version of New Yorkers. Here we have a loving couple just needing a sexual escapade to launch them into the perfect marriage. There we have a comic-infused undertaker just waiting to be discovered as an opera singer. Everyone is modern and amoral and sophisticated.

But where are the nuns?

You can’t throw a cannoli in Rome without hitting a nun or priest. Yet, they are M.I.A. from Allen’s movie. Allen’s characters frequent little cafes and walk ancient streets, but don’t enter the churches.

And that’s what Rome is all about, isn’t it? On every corner, art, monuments, cathedrals, statues, and the very framing of architecture point to humanity grappling with the universe, with God, with destiny.

Let’s start with the eight Egyptian obelisks that dot the city. For the most part, they were plundered from the more ancient Egyptian empire during the height of the Roman Empire before the Christian era, a pagan empire plundering the riches and gods of a formerly powerful and long-lasting people. There they stand, although the religion and empire that built them has long crumbled, along with the religion and empire that plundered them.

Or take the Pantheon, built by the Emperor Hadrian in 118, when the Empire seemed destined to last forever and the chorus of Roman gods the apex of all gods. Little did he suspect the seeds of revolution were already sprouting in his empire. They weren’t political revolution – that had been dealt with before, harshly – but a revolution in the very concept of what it means to be human, a revolution that would strip him and his successors of divine status and the gods of their glory.

Take the Coliseum, mentioned in the movie, where adherents of a new faith would die before beasts and gladiators, or the catacombs, where the faithful hid among the dead to worship.

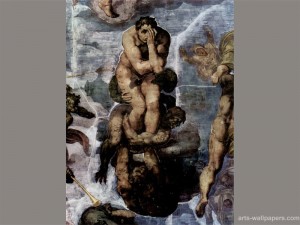

Or focus on the Christian era, where corruption and faithfulness battled for a thousand years, where great glory mixed with great shame, and continues to this day. This is the awe-inspiring nature of the Vatican, with its Sistine Chapel altar wall by Michelangelo so vividly showing the struggle between Heaven and Hell, good and evil, salvation and damnation.

None of this weight of history cares much about one neurotic man’s ambition to find a new singer, nor of sexual escapades, nor of the wild and semi-regretted affair with a troubled girl.

Allen is Jewish, a people who have their own long history with Rome, but that doesn’t factor into the movie either. He works hard to avoid all mention of the transcendent.

The very thing Woody Allen specializes in – staring into the trivialities of one’s own experience to highlight the absurdity there – will not do in Rome.

In Rome, triviality washes away, along with the individual.

Allen hints at this. Two different characters bring up “ozymandias melancholi,” the melancholy brought on by the weight of ruins, the feeling that life and empires flash by and nothing lasts forever. But they only speak of it; they do not become changed by it.

Rome – and humanity in general – handles this melancholy by embracing the eternal, coming to terms with mortality, usually by finding faith.

Woody Allen handles it by doubling down on the trivial.

It seems he is incapable, when in Rome, of doing as the Romans do.