Over the this turn of the “Wheel of the Year”, we are investigating and paying respect to eight archetypes of mature, sacred masculinity. The Captain At Lughnasadh/Lammas is the sixth installment in this series.

Context

(If you’ve been reading this series, you can skip this repeating section.)

Men’s mysteries matter. Today, young men are confronted on one hand with reactionary voices who advocate gender roles decades or centuries out of date, and on the other with professional-managerial class “progressive” voices who seem to think the answer to the reactionaries is to eliminate masculinity.

The transition to manhood is dangerous. Men are both more likely than women to be murdered and to commit murder. We’re more likely to be in prison, to be killed on the job, or to commit suicide. We’re less likely to finish high school or earn college degrees.

Boys who fail to make a successful transition to manhood end up at best being a drag on society, and at worst an active threat to people’s lives. And we will not help them make the transition by denying that manhood even exists.

To help young men through the transition, a system of archetypes can be a useful guide. No such system will be complete, of course. What I’m going to talk about in this series of posts is inspired by the book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, and also by Robert Bly’s work, but it’s my own thing. Anything smart is probably copied from those others and anything dumb here is probably my own fault.

By considering these archetypes I am not claiming that these roles are unavailable to women or nonbinary folks. Nor am I claiming that this is the only way to be a man. I’m offering some ideas that have helped me come to terms with my own existence as an adult male human being. (And cognizant that that is as a “white” heterosexual American male, though still believing there’s enough universality in the way androgens shape our brains for the exercise to be useful). If they don’t work for you, fine, please tell us your secrets! If you’re not a man and find that they work for you, great!

For each of these archetypes, we’re going to discuss a balanced version, an excess version, and a shadow version.

Visualize us going around a mountain: at the top is the Wild Man and the realm of excess, up where the air is thin. It’s exhilarating but we can’t stay there. At the bottom is the shadow realm of fear. The healthy mature man moves around the middle heights of the mountain, in neither shadow not excess, moving between the archetypes as needed. Over this series, we will visit eight points around the mountain: the Magician, the Healer, the Lover, the Preacher, the King, the Captain, the Warrior, and the Trickster.

The Captain

Over his life, a man may be called upon to exhibit several different types of leadership. We’ve talked about the moral leadership of the Preacher, whose moral authority is rooted in how he lives his life; and the spiritual leadership of the King, whose very presence inspires and who acts as the conduit of blessings for his people.

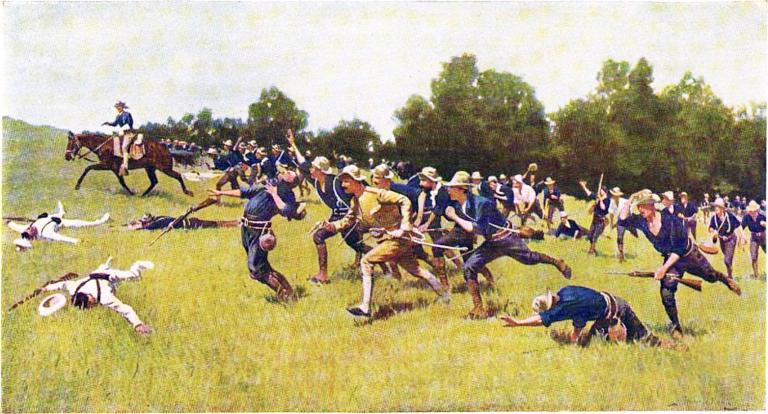

In contrast, the Captain is a more practical leader, leading men in direct action. The Warrior (whom we’ll discuss next) is defined by his Mission — his task, his purpose — and his actions in support of that mission. The Captain leads Warriors in accomplishing their mission.

Many of the Kings of our mythology were Captains of battle first. King Arthur must conquer before he reigns; while in The Lord of the Rings Strider’s arc is to move from Warrior (a Ranger, acting alone) to Captain (leading first the Fellowship, then the Army of the West) to King. Perhaps this is a reflection of our bloody history of conquest; perhaps it’s just because battles make for rousing part of stories.

In many of these stories, the throne is empty, the Good Order of the World is out of joint, and someone (historically, and so also mythologically, a man) must step up to put things right. The King-to-be proves his ability to be that man by leading a first a small group, then larger and larger groups, out-competing all challengers; moving from structuring a small band of men in a practical goal, to becoming the incarnation of the structure of the world. But in that process he becomes more and more distant from those he leads, less a practical man of action and more concerned with the abstract. A mature man must be able to take on either of these roles as appropriate.

It’s noteworthy that the Captain can be a more democratic figure than the King. On pirate ships during the “golden age” of piracy, a captain would often be elected by the crew. In battle his authority was unquestioned, but part of that was because he was the men’s choice.

The idea of an unquestioned leader in action chosen by free election beforehand has occurred in other points in history. The Minutemen of the American colonial militias elected their officers, and anarchist militias in the Spanish Civil War similarly elected their commanders. We might also look to the way in which ancient Athens elected strategoi.

And of course the American President’s role as an elected Commander-In-Chief or the military has echos of this. When Lincoln was assassinated, Walt Whitman, self-styled bard of democracy, turned to the image of the Captain rather than the King in order to eulogize him:

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

There is a cliche that the boss says “go” while a leader says “let’s go”. This is a bit of an oversimplifiction — when we discussed the King, we saw how there is a place for the leader who is further off, an inspiring mythic incarnation of the community or principles in question — but this is a good way to view the distinction between the King and the Captain. The Captain is in the field or on the ship with those he leads, in the fray with them, leading the charge, while the King may be on the other side of the world. Men fight in the name of the King, but it is the Captain they follow into the hell of battle.

And the Captain cares directly for his men. He is mentor and caretaker, even if he can also be a stern taskmaster. The Captain goes down with the ship because he puts his men ahead of himself. But as a leader of Warriors, he puts the mission before all.

Shadow: The Martinet

Where the Captain puts his men ahead of himself, and uses the command hierarchy as a means to accomplish a Warrior’s mission, the Martinet loves hierarchy and rules for their own sake, so long as the structure put him on top. He puts himself above both his men and any idea of a mission.

Where the Captain is a leader of Warriors, the Martinet is a leader of bullies, the top dog — until he is pulled down by a stronger bully.

We all know the Martinet. He is every petty manager who delights in lording power over his staff.

Excess: the Vanderdecken

According to legend, Captain Vanderdecken (sometimes written as Van der Decken) was the captain of the Flying Dutchman. Like all good legends there are many versions and variations, but the core of the story is that the ship was rounding the Cape of Good Hope and the wind was against them, and the captain vowed that he wouldn’t give up until Judgment Day, and so his ghost ship is still there:

She was an Amsterdam vessel, and sailed from that port seventy years ago. Her master’s name was Vanderdecken. He was a staunch seaman, and would have his own way, in spite of the devil. For all that, never a sailor under him had reason to complain; though how it is on board with them now, nobody knows. The story is this, that in doubling the Cape, they were a long day trying to weather the Table Bay, which we saw this morning. However, the wind headed them, and went against them more and more, and Vanderdecken walked the deck, swearing at the wind. Just after sunset, a vessel spoke him, asking if he did not mean to go into the Bay that night. Vanderdecken replied, ‘May I be eternally d__d if I do, though I should beat about here till the day of judgment!’ And to be sure, Vanderdecken never did go into that bay; for it is believed that he continues to beat about in these seas still, and will do so long enough.

The Captain who would not yield…even to Nature or God, and so damned not only himself but his crew. The Captain must remember that he is responsible for the lives and welfare of his men, and not let his ego or pride lead him to destruction for the whole company.

The Captain at Lammas / Lughnasadh

What’s in a Name?

Way back in the 1990s when I was a twenty-something newly minted Pagan with a Wheel Of The Year poster on my wall, that poster noted the August cross-quarter day as “Lammas”. (And on August 2, not August 1.) It will always be Lammas to me, but more people seem to know it these days as Lughnasadh or Lughnasa.

Lugh Who?

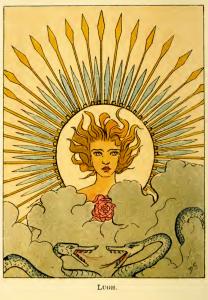

Lughnasadh is “the assembly of Lugh”, a feast day founded by the god Lugh, the war captain of the Tuatha De Dannan in their battle against the Fomorians. Some stories say Lughnasadh was founded in honor of the memory of a dead goddess, in some stories his foster mother, in others his wife. Other stories have the origin being a celebration of Lugh’s victory as a harvest god over a tyrannical sun god.

Lugh is a great Warrior and a great leader of Warriors, and skilled in many arts: a smith and a Magician and a Healer and a poet and a harpist, so that one one his epithets is Samildanach, “many-gifted”; and some tales have him related to Kingship. But when battle is joined between the Tuatha De Dannan and the Fomorians:

…When the battle began, Lug escaped from his guardians with his charioteer, so that it was he who was in front of the hosts of the Tuatha De.

Then a keen and cruel battle was fought between the tribe of the Fomorians and the men of Ireland. Lug was heartening the men of Ireland that they should fight the battle fervently, so that they should not be any longer in bondage.

Lugh is not a King distant and isolated, but a Captain, at the vanguard of his Warriors, giving them heart and leading them to victory.

So Lughnasadh is a good time to consider your relationship with this archetype.

Evocation of the Captain

I evoke and call forth

The Captain within me

I honor and acknowledge

My ability to take command

To lead by example

To be guardian and caretaker of those I lead

I will use authority and discipline as means to an end

Never as an ego-engorging end in themselves

I resolve to be worthy of the trust others put in me

And use it in service of a proper Mission

Never throw away the lives or treasure or energy trusted to me

for petty ends

So mote it be.