Today I’d like to discuss one of my favorite historical speculations. I want to be clear right off the top that we are in the realm of “possibly” and “could be” here, that you should raise an eyebrow at this idea…but I find it fascinating, a possible (possible only!) confluence of two reactions to industrialization and modernity around the turn of the 20th century.

The speculation is this: that both the Boy Scouts and modern Wicca can trace a significant part of their heritage to a naturalist, mystic, author, and advocate of Native American culture who was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but mostly unknown today. In the case of the Boy Scouts the history is clear, though largely forgotten for political reasons. For Wicca, it’s a foggy connection at best, but there is evidence for some sort of connection.

John Michael Greer and Gordon Cooper’s article “The Red God: Woodcraft and the Origins of Wicca”, published in Gnosis, Summer 1998, was one of the first articles (maybe the very first?) to explore this connection, so credit to them. What follows is mostly adapted from my book, Why Buddha Touched the Earth. For further references, well, buy the book! 🙂

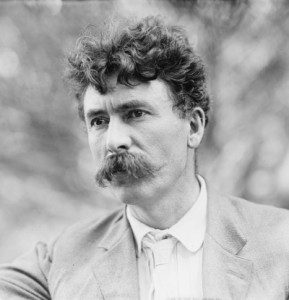

So. Gerald Gardner, generally regarded as the founder of modern Witchcraft, claimed that he was initiated into a witch coven in 1939, and that this coven was a genuine remnant of pre-Christian European religion. The existence and nature of this coven is one of the big mysteries in Neopagan history, but it’s generally accepted by historians that this was not some bit of continuous ancient native religion. (Sorry to disappoint any true believers.)

I am not a Wiccan, let alone a Gardnerian, but I find that I like Gardner. Nothing here is meant as an attack on him. But we know that he had, in the words of his student Frederic Lamond, a “devious creative attitude to factual truth.” (That’s part of why I like him!)

He made false claims of scholarly credentials including non-existent Ph.D. In one book he falsely claimed to be a disinterested observer of witchcraft rather than admitting to his involvement. And he claimed that the coven was led by a woman named Dorthy Clutterbuck, who seems to have been a pious Christian with no links to any sort of witchcraft; he may have used her name either as a prank, or as a blind to conceal the identity of the actual leader.

In Gardner we have an unreliable narrator; his account must be taken with salt.

This much seems clear: after more than three decades working in the British colonies in Ceylon, Borneo, and Malaya, Garner retired to England in 1936. In his time overseas he observed the religious and magical rites of the Dyak and Sakai tribes, and studied the mythology and folk magic of the Malays — especially the part involving their traditional blade, the kris. He became interested in anthropology and archeology, and his work was published by the Royal Asiatic Society. In Ceylon he encountered Buddhism; he was interested by its idea of reincarnation (or at least the popular interpretation of that teaching) but that seems to have been the extent of its impact on him.

On one of his occasional visits to England he became interested in Spiritualism; he believed that some mediums had a genuine ability to contact the “spirit world” and speak to the dead.

So by the time he retired, Gardner had studied a variety of religious practices.

In 1938 he moved to the New Forest district of Hampshire. Nearby he met a “Rosicrucian Theatre” group which seems so ridiculous one could almost seen it as a parody — its leader claimed to own the Holy Grail and to be immortal! But there was a small clique that he got on well with, the group he later identified as a coven.

Who were they really? Was there really a group doing some interesting religious and magical work, or did Gardner attribute his own ideas to others to lend them weight?

We don’t know if Gardner’s coven was real — but we do know that there were groups doing interesting religious and magical work in the New Forest area around that time.

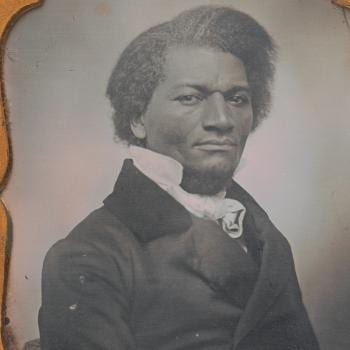

Press pause now on Gardner’s story, and turn now to a man who made a large impact on Western culture during the “Progressive Era” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries but is now mostly unknown: Ernest Thompson Seton.

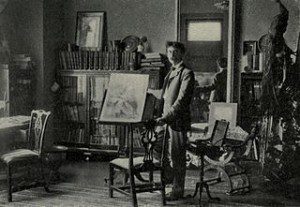

Seton was a naturalist and explorer, a popular artist and writer, and an early conservationist. But it was his work popularizing Native American culture and spirituality, work that led to the formation of the Boy Scouts, that had the most lasting impact — even as he himself has been largely forgotten.

He was born in England in 1860, and his family moved to upper Ontario to become homesteaders near the town of Lindsay. They failed at farming and soon moved to Toronto, but the young Seton had grown to love the woods around Lindsay, and his mother arranged for him to spend part of his summer vacation there each year.

During these visits he spent time with neighborhood boys, camping out in the woods in homemade tepees and playing at being Indians. He met an old woman he called the Lindsay Witch — and isn’t that interesting? — and learned a lot of wood-lore from her. His book of children’s stories Woodland Tales has a story “The Wood-witch and the Bog-nuts” in which “Granny Wood-witch” teaches a boy about the edible ground nut; perhaps this character is a tribute to that witch.

In 1879 Seton went to London to study art at the Royal Academy. He attended classes only briefly, but was inspired by reading naturalists like Audubon and Thoreau at the British Museum. In London he lived a self-denying, sexually repressed, ascetic life — partly from poverty, but partly from a disposition towards it. He began to have mystical experiences, hearing a “voice” which urged him to go to Western Canada and then to New York.

He followed that voice and spent much of the 1880s moving between homesteading attempts, nature watching, and art and natural science work in the U.S. and Canada. In this time he became acquainted with members of the Cree and Sioux tribes. He studied several Native languages and was an early member of the Sequoya League, a group dedicated to improving conditions for tribes on the West Coast.

By 1902 he was personally acquainted with several tribal chiefs, was acknowledged as an expert by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, and was honored by his Native friends by being one of the first whites to be made a “pipe carrier.” A few years later his ideas about Native American spirituality would find hundreds of thousands of followers in the U.S. when he created the “Woodcraft Indians”; later his work inspired groups in England, including near New Forest, to organize under the Woodcraft banner — but with a more Ancient British than Native American flavor.

How directly did this mystic, friend and advocate of Native Americans, co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America, and student of a witch influence the development of Gardnerian Wicca, and the broader Neopagan movement? Well, I don’t know! But stay tuned: we’ll have more history and speculation about this fascinating proto-Pagan in Part II.

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

My next scheduled event is Starwood, July 7-13.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there,

too.