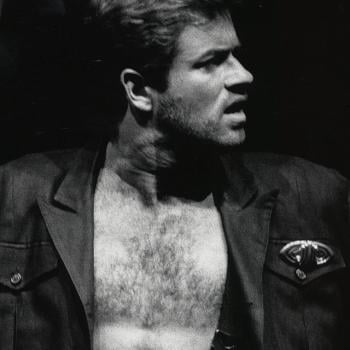

“Depeche Mode’s ‘Personal Jesus’: Preaching to the Masses” is the third in the series of analyzing pop culture through a critical Christian lens. The first reviewed George Michael’s “Faith.” The second in the series addressed Tori Amoss’s song “God.”

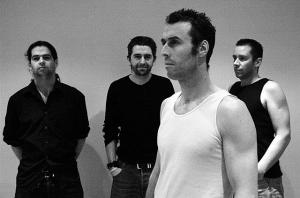

“Personal Jesus” – Depeche Mode, Official Video

The remastered version

A Personal Jesus?

According to Martin Gore, who is cited in “Pop a la Mode” (Vol. 6, no. 4) , the songwriter for the track,

“It’s a song about being a Jesus for somebody else, someone to give you hope and care. It’s about how Elvis Presley was her man and her mentor and how often that happens in love relationships; how everybody’s heart is like a god in some way. We play these god-like parts for people, but no one is perfect, and that’s not a very balanced view of someone, is it?”

The book, “Elvis and Me” (1985), written by Elvis’ wife, Priscilla Presley, sparked the interest in the faith of another stemming from the love shared for the person. The marketing of the work is a brilliant model of reaching an audience. The band placed an ad in the classified section of British newspapers asking readers to call a listed phone number to access to “your own personal Jesus,” providing a preview of the track before the release of the single.

Martin Gore wrote about the meaning of the track.

“It’s a song about being a Jesus for somebody else, someone to give you hope and care. It’s about how Elvis Presley was her man and her mentor and how often that happens in love relationships; how everybody’s heart is like a god in some way. We play these god-like parts for people but no one is perfect, and that’s not a very balanced view of someone, is it?”

The track “Personal Jesus” came out on August 29, 1989, reaching a certified gold in the US and being the band’s longest Germany chart top-ranked track for 23 weeks. Slant Magazine writes about the track in their Best Singles of the 1990s (January 9, 2011), Driven by an a-typical acoustic guitar, a throbbing muted drum pulsation, and a lighter synthesizer landscape, this track extends the ouvre of Depeche Mode following a two year hiatus. Their classic minimalist lyric style remains intact. The haunting hook, “Reach out Touch Faith/ Your Own/ Personal Jesus,” finds a secure place in the pop music lexicon. The placement of the hook nestled between the rhythmic pattern and emphasized with a powerful descending electronic string-brass fabricated line, the hook itself draws and retains attention.

Slant magazine (2011) writes about the track as one taking the band on an introspective journey with a bend to their electronic-centered foundation.

“Depeche Mode’s gimmick is one that, after years of repetition, seems ingeniously flimsy, bundling angst and spiritual frustration with sex and pouty gloom. ‘Personal Jesus’ has escaped the mustiness that has enveloped most of the band’s material not by flouting these tactics but by embodying them so well. Bolstered by Dave Gahan’s repeated imprecation to ‘reach out and touch faith’, the vocals seem perched on a neutral point between the completely earnest and the bitterly sarcastic, turning what could have been another flat religious diatribe into a thinly dual-tiered assessment of devotion and self-absorption.”

The point of articulating a sense of faith and belief is interesting coming from a pop group and deserves further uncovering.

Looking for Jesus?

The video takes place in a desert location. Shot in all black and white, leading objectifications of color are removed, situating the work as a binary narrative. The equal four band members are aligned with four females. The sexual innuendos expressed by the women with slight reference from the band members, mainly the frontman David Gahan, is a juxtaposition against the lyrics. The narrative line is about searching for Jesus. The subtitle narrative is about reaching out to hold onto (“touch”) faith. If the sexual references are included, the video reads that physical desire is central when contextualized in a vacant, barren location – the open desert scene used for the video. This would align the personal Jesus being sought after as capable of being reached and held onto from physical contact. “Faith,” then, is reduced to a physical standard. The “someone to be your friend/ someone to care” must be an individual capable of embracing. “Faith” is predetermined by a worldly definition and must be seen. This is a counter narrative to scripture, which states that faith is in that which is not seen,

Faith shows the reality of what we hope for; it is the evidence of things we cannot see. (Hebrews 11:1 NIV)

Taking this reading further, the band members all wear sunglasses throughout the video, while the women do not. This would imply that males are not capable of seeing faith. The women, in contrast, are the ones capable of seeing faith. David Gahan is seen extending his arms out multiple times throughout the video, concluding with a folding of his hands as in a prayer. Gahan serves as the metaphor for the male band members; his faith is blind and reaching out to hold onto what is present (the women), yet is unable to grab a firm hold of what is assumed as “faith,” a physical contact. The “someone to be your friend/ someone to care” is echoed as an individual cry for faith. Blinded by the sunglasses, Gahan and the band members are not able to see what they conceptualize as “faith.” Their lack of faith (read: trust) in what is not present keeps the band members from constructing faith. The “personal Jesus” is framed as the need for physical connection. The women, open-eyed, see no need for faith. They embody a position of physical desire (read: a word-centered value of faith), a metaphor of “faith.” The women do not hold the space of being the “personal Jesus.” Rather, they manipulate what the band members seek to find and blindly believe is their personal Jesus, an individual to be their companion, someone to care for. The women transpose “faith” from a scriptural position to that of a physical, tangible identity.

Calling Jesus

The lyrics to the track follow with Depeche Mode’s minimalist approach. There is only one verse with an added sub-verse and chorus/hook.

Reach out/ Touch Faith

Your own personal Jesus

Someone to hear your prayers

Someone who cares

Your own personal Jesus

Someone to hear your prayers

Someone who’s there

Feeling unknown

And you’re all alone

Flesh and bone

By the telephone

Lift up the receiver

I’ll make you a believer

Take second best

Put me to the test

Things on your chest

You need to confess

I will deliver

You know I’m a forgive

The first verse situates two perspectives, one from an observer of the individual presumably seeking out, or “reaching out” for faith, and the other from a third person. The first lines, “Feeling unknown/ And you’re all alone/ Flesh and bone/ By the telephone” gives the observer’s view of the situation, the point of the object being viewed is an anonymous human (“flesh and bone”), and their location, isolated by a telephone. Why the telephone? Coinciding with the band’s marketing strategy of posting a number in British newspapers, this gives liberty to the observing human to reach out for a device to receive faith and belief- “Lift up the receiver/ I’ll make you a believer”. At this point, the perspective flips. Is this perspective Jesus who is reaching out to the “flesh and bone” (read: mankind)? Directing the unidentified person in the track who sought to reach out to touch faith, the action of these two lines qualifies this request. By suggestion, not demand, the subtextual lyrics from the perspective of Jesus provide the person the way to receive concrete belief extending to the desire for faith, lift up the telephone receiver and listen to the voice on the other end. A simple gesture notably transformed the searching person into a believer. The presumed unknown voice on the other end of the telephone line, Jesus, provides blind belief, fortifying the person’s faith in what they are hearing. This aligns scripture’s understanding of faith being founded on things unseen (Hebrews 11:1). Having the last word in this stanza, “believer” works in a cycle to the person seeking faith. If you want to believe, don’t trust in your isolated position; hear the voice of the unseen Jesus, and this will bring you to believe, establishing the faith being sought and situating a personal connection with Jesus.

The second stanza follows a similar narrative without leaving the perspective of Jesus.

Take second best

Put me to the test

Things on your chest

You need to confess

I will deliver

You know I’m a forgiver

Each line works to develop a connection with Jesus. Through a human perspective, the unidentified narrator’s understanding of who Jesus is localizes the idea of Jesus in a diminutive context rather than as part of the triune God (Father, Son, Holy Spirit).

“Take second best” can be seen as pointing to the assumed position of the narrator from the perspective of Jesus: “You are second best overall.” The following line, “Put me to the text,” highlights the voice understood to be Jesus in this verse. “Things on your chest/ You need to confess” places an emphasis on the act of confession of sin and the human weight it holds for a non-believer, one who is absent of faith.

“If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.” (1 John 1:9, NLT).

The biblical reference captures the remaining lines of the verse, “I will deliver/ You know I’m a forgiver”. For the band to situate this powerful statement in a pop song on a global platform is a bold move and one that may have gone under-represented, given the strong sonic landscape of the work. This second verse moves the context from an earthly, human construction of the idea of Jesus to one framing the act of repentance leaning toward the acceptance of salvation. Juxtaposing this second verse with the video, the explored physical desire of the female icon is transformed into the act of confession and forgiveness. “Faith,” then, has transformed from an external visualized belief to an internal invisible belief. “Jesus,” for the original voice of the track is no longer a figure of imagination, but one of inner desire in belief worth reaching out toward to secure faith. Captured in six lines, the second verse transforms the seeking inquiry of the first verse into one pointing toward the foundations of honest faith, belief, and a relationship with Jesus. The assumed idea of Jesus has grown from an objectification to a spiritual indoctrination through faith. The hook, “Reach out/ Touch Faith,” segues from a secular definition of manipulation to the possibility of a secure embrace, or belief in Faith.

The odd line in the chorus, “Someone to hear your prayers,” subtly underscores this transformational point. The only reference to a physical prayer is the closing visual, with David Gahan folding his hands as if he were in prayer. This begs the question, “To whom is he praying?” The gesture at the end of the video leaves the viewer hanging on an unanswered question. Has the original voice of the lyrics crossed from a position of a non-believer to a believer? Is the “personal” now the relationship with Jesus, moving away from the self-constructed idea of a Christ figure? David Gahan’s arms are stretched out before the slow folding of the hands – forming a posture of prayer – rhetorically answers and avoics the question simultaneously. The praying hands conclude the video’s last seconds (3:39/3:40), yet throughout the video, the closest reference is the stretched arms as a metaphor for seeking faith and Jesus.

Throughout the video, the band members have their eyes covered. The women hold a firm location in the video as icons for desire. The women and band members never arrive together as suggested in the hyperbole, given the proximity of all in the video at different points. The women reference a wishful prayer, their desire for “someone” in friendship and care. Extending the concept of faith, defined by the luring willingness to embrace the female object, “Faith” is scripted as an item to physically hold, manipulate on a personal level, and only provided through a hyper-sexualized icon, the reified woman of desire. Faith, in this reference, is not in the things unseen. Faith is residing in the invisible personal desire to generate a physical reference to be controlled and used.

Leaving the video with a rhetorical physical gesture invites the viewers to determine their response to the overall mechanics of the track-video relationship. Has the original voice, performed by David Gahan in the video, actually found faith? Therefore, the reaching, opened, desireing arms no longer need to be in the position. The folded hands as a sign of prayer qualify the overarching theme of the track: a personal relationship with Jesus, as the one who cares and offers friendship, is possible from first listening to the voice of Jesus, moving through confession, and resulting in a faith-based belief in Jesus. The “personal Jesus” is not a metaphor of humanly desire; it is the in-depth desire for a relationship with Jesus, and it is possible.

A Call For Discipleship?

The gravity of the song brought about several cover versions by Johnny Cash (2002), Marylin Manson (2004), Def Leppard (2018), Iggy Pop, and Mindless Self Indulgence.

Each of these covers demands an analysis. The depth to which each version provides using the overarching theme of seeking a connection to a faith and belief highlights the sensitivity and pointed tone of the original Depeche Mode recording. Why would such a vast collection of artists/bands see the value in recording a cover of the song? Is the tenor of the work such that to prompts a personal response in support of the work? A cover, by nature, provides an expanded or varied presentation of the original work. These cover recordings each qualify the mechanics yet include a reading of the work as it resonates with their artistic voice.

Johnny Cash exposes a very personal journey through his career and life. Using the backdrop of his rise and fall to become a more sound believer in Christ, Johnny Cash does not stray away from this expose in the video. The crumbled tone of his lyrics and classic rock-a-billy style frames Johnny Cash’s life alongside the transformation spirit of the original.

Marylin Manson takes a socio-political response with hyper-sexualized images, expanding the brothel concept of the original video. The work for Marylin Manson threads a rhetorical response to organized religion in different points in the video. The strong gothic nature of the work is Marylin Manson’s classic style. Juxtaposed to a song navigating from seeking to personal embracing of faith, Marylin Manson does not follow this narrative. This cover positions the original as a question to the listener/viewer: “Do you have a personal Jesus?”

The hard rock hair band of the 1980s, the well aged band Def Leppard elects to troupe on elements of the original embedded in their classic distorted power chord sound. Retaining the original’s black and white visual context, the band is shown performing the work throughout. Slices of pop culture images are delicately placed throughout, typically coinciding with the guitar riff breaks. Trouping back to David Gahan’s closed praying hands and extended arms gesturing to signify a reaching out for faith, this cover provides a mature position of the original. The inversion to the original is the praying hands are broken, released from the praying posture in one caption. In the following scene, the hands return to the praying posture. As with the other covers, Def Leppard prompts a rhetorical question: “What is your personal Jesus?” This is gained through the portrait positioning of the band and the inserted pop culture images referencing themes that are often elevated to a position of personal importance over that of faith and belief in Jesus. Updating the acoustic sound with a signature grinding guitar-centered tone, Def Leppard signifies on the original work while adding their fingerprint to this oeuvre.

Iggy Pop works closely with the cover by Johnny Cash. Without any video, this cover relies solely on the soundscape to make a point. The quasi-gospel, blues influence is a tip to the original. The lazy, heavily articulated voice is a nod to Johnny Cash. The internal vocal gestures are pure Iggy Pop. Keeping close to the acoustic nature of the original work, Iggy Pop explores a pastiche of suggestive religious sounds to highlight an understanding of how faith and belief are central to the theme. In line with the other covers, Iggy Pop positions the question, “Do you have a personal Jesus?” Depending on which video is referenced, Iggy Pop is either seen in a broken black and white texture with a questioning stare articulated by a clasped left hand on his chin. Another audio version has the words “IGGY” atop the word “JESUS” in blood block lettering. The other words are minimized, transparent, and invisible. The suggestion can be read as Iggy being the one who cares and is bringing you a personal Jesus through this representation. It can also be critiqued as man over God, outlining a more secular approach to Jesus, thus making the cover a commodity – and Jesus by association – for public consumption. Absent any visual influence, a listener is stuck in this binary. How does the listener escape from this visually arresting statement? The question Iggy Pop subtextually offers, as well as the other cover versions, “Do you have a personal Jesus?” Based on the individual’s answer to the rhetorical question will, or should, point to how one can be released from the visual shackles.

The most dramatic approach to the original is by Mnidless Self Induglence. The soundscape replaces the strong acoustic tone of the original for a pure synth-driven sound. The video itself takes a completely different approach, incorporating provocative anti-religious, anti-Christian images and storyline. The widely suggestive images convey a similar question to the listener/viewer as Marilyn Manson, “What is your personal Jesus?” Framing the work in such a dark anti-religious, anti-Christian perspective may appeal to those outside of Christianity. This version does more to defeat the importance of the original for a non-faith audience. Engaging radical, sexually explicit images and counter-religious overtones, one leaves this version with the shock value the Mindless Self Indulgence is known to produce.

The Persistent Reaching Out

Each of these cover versions keeps to the lyric structure of the original. This is an interesting point that underscores the value of the simple two-verse, chrous song. It would be expected for some variation or departure from this structure would be present. The stability of this form by such contrasting artists/bands gives strong value to the original work by Depeche Mode.

Critical acclaim for “Personal Jesus” by Depeche Mode may not be such a far cry. Recalling the global audience attraction of this work and its place inside of the top 500 best songs, Depeche Mode made the world consider what a relationship with Jesus could be. The rhetorical questions in the covers demonstrate the ongoing inquiry into what a personal connection is to religious doctrine, faith, and belief. Reaching out to touch faith, at first, sounds simple. Depeche Mode, along with the subsequent cover versions, asks, “What is the faith you are reaching toward?” The song opens the door for secular audiences to evaluate a connection to faith, an understanding of religion, and belief in Jesus. Providing no direct answer but contextualizing a transformation through the lyrics, Depeche Mode shares the pop cultural possibility for Christian faith to be inserted in the dialogue. Was this understood by audiences, record critics, album reviewers, and those who only came to know this work by one of the different covers? The fact that this work has found a firm placement in pop cultural history tosses the question back to the listener: “What is your connection to faith? And are you reaching out to discover your personal connection with Jesus?” In all, Jesus is not a metaphorical figure some secular reviewers would like to propose. There is a connection, the internal desire to have a faith-based relationship with Jesus. Depeche Mode simply offers up the question.