Juneteenth — June 19 — is an official holiday now, commemorating the ending of slavery in the U.S. This is an accomplishment worthy of commemoration, of course. But I do wish that politicians and news media would get the history right. Every year we’re subjected to a mangled narrative of what happened on June 19. 1865, that doesn’t exactly match the facts. Compulsive history nerd that I am, I must explain what the narratives get wrong.

On June 19, 1865, a Union general announced to enslaved people in Texas that they were already, legally, free. That much is true. So, the story goes, this was the end of slavery in the United States. But in fact, slavery didn’t end in Delaware and Kentucky until December 1865. This involved about 100,000 people who remained in slavery for six more months after Juneteenth. That part always gets left out. And if you are curious to find out how that happened, please keep reading.

And while we’re at it, let us remember that the abolition of slavery was very much a religious cause in the antebellum United States. As I wrote awhile back, in Christianity and the Abolitionist Movement in the U.S., the earliest documented protest against African slavery in North America was made in 1688 by a group of Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania. In the 18th century many preachers began to denounce slavery as sin. The abolitionist movement gained momentum from the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revivalist movement of the early 19th century. While southern Christian clergy did use scripture to make excuses for slavery, northern clergy were leading the abolitionist movement to end slavery everywhere in the U.S.

The First Juneteenth

Getting Juneteenth right requires getting the U.S. Civil War right. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, slave states in the South began a process of formally seceding from the United States to form their own confederacy of states. They did this to protect the institution of slavery from being abolished. Period. Secession was not about “states’ rights” or tariffs or any other dadblamed thing Confederate apologists make up today; it was all about protecting slavery. Official documents of the period, as well as the letters and speeches of Confederate leaders at the time, are crystal clear on this point. The plantation owners of the South were frantic to maintain legal slavery because they didn’t believe their labor-intensive cash crop, cotton, could profitably be produced if they had to hire the help. In contrast, by 1817 most northern states had either abolished slavery or had committed themselves to be done with it by some future date.

It was well known that Abraham Lincoln opposed slavery. However, Lincoln was not about to abolish slavery in the southern states. It was widely understood that abolishing slavery everywhere would require a Constitutional amendment, and in 1860 that looked impossible. But in 1860 most of the territory west of the Mississippi was federal territory. Most of it hadn’t yet been admitted to the Union as states. And Lincoln’s main campaign promise was to keep slavery out of the western territories. The plantation owners feared that eventually there would be enough “free soil” states to ratify an anti-slavery amendment. Seceded states officially formed the Confederate States of America in February 1861. The Civil War began in April 1861 when Confederates attacked a U.S. military garrison, Fort Sumter, which was on an island off the coast of South Carolina.

The Emancipation Proclamation

It was a very difficult war. Through 1861 and 1862 not much went right for the Union. Weighing on President Lincoln was the fact that there were four slave states — Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri — that had not yet seceded. Lincoln didn’t want them to secede and make the Confederacy bigger, and so he was careful to avoid enflaming those states’ slave owners. For example, in August 1861 Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, commanding the Department of the West, issued an emancipation proclamation that would have freed people enslaved in Missouri. Lincoln promptly relieved Frémont of command and countermanded the proclamation.

Lincoln had another worry, which was that some European powers might enter the war on the side of the Confederacy. Before the war, the southern states were a major supplier of raw cotton to Europe. But during the war a naval blockade kept all that cotton locked up in southern warehouses. European textile mills, especially in Britain and France, were sitting idle. British industrialists were pressuring Queen Victoria’s government to take the side of the Confederacy. But there was much anti-slavery sentiment among the people of Britain. Victoria’s beloved husband Prince Albert, who had died in December 1861, had also been a very outspoken opponent of slavery.

The famous Emancipation Proclamation that “freed the slaves” went into effect in January 1863. In truth, the Proclamation didn’t free anyone right away. It declared that enslaved persons in the seceded states were free, which was not something enforceable at the time. It did not free enslaved persons in the Union slave states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, or Missouri. There also was an exception for Confederate territory that might be occupied by Union troops. The significance of the Proclamation was that it made freeing enslaved people an eventual outcome of a Union victory. And that meant Queen Victoria’s government would not become allied with the Confederacy, no matter what the textile mill owners wanted. France decided that if Britain wasn’t getting into the war, it wouldn’t, either.

Juneteenth: What Happened Next?

In the later months of 1864 Union troops were marching through significant amounts of Confederate territory. A number of plantation owners fled to the Confederate state of Texas, far from most of the battles, taking people they had enslaved with them. The war ended in April 1865 with a Union victory. There were still some pockets of resistance that needed attention, however.

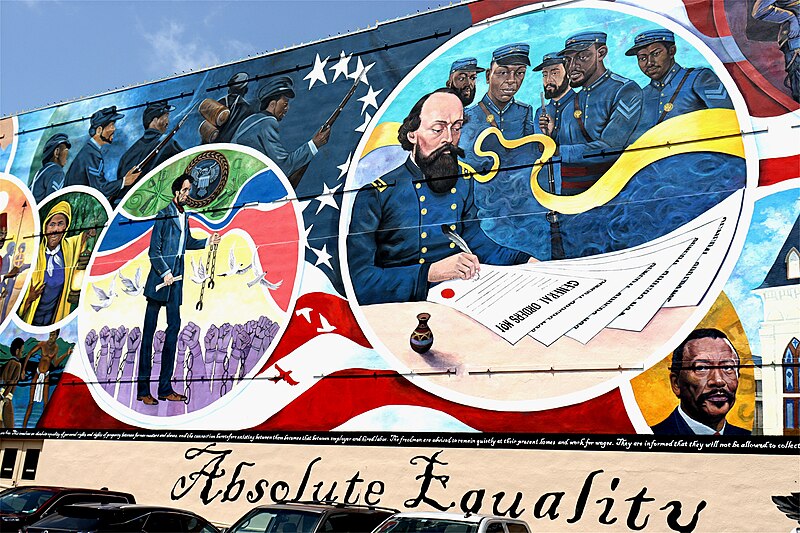

On June 19, 1865, Union troops — including regiments of the United States Colored Troops — arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. And on that day, Union General Gordon Granger proclaimed that slavery already had been abolished in Texas. The date was ever after remembered as “Juneteenth.”

Indeed, all people who had been enslaved in the Confederate states were free when the war ended. But that left us with Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. The Maryland legislature had ended slavery within the state in 1864, and Missouri ended slavery in January 1865. Slavery didn’t end in Kentucky and Delaware, however, until the 13th Amendment was ratified in December 1865.

On December 18, 1865, the Constitutional amendment that ended slavery went into effect, and on that day more than 100,000 people enslaved in Kentucky and Delaware were freed. And that day, December 18, was the last day of legal chattel slavery in the United States.

I’m not saying it’s wrong to commemorate the ending of slavery on June 19. The important thing is that we remember. All of us. And December already is a bit overloaded with holidays.

And, yes, I had to explain that. I feel better now. Happy Juneteenth!