Pope Francis, aka Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, has died. As to the man and his present status, the most I can say is “who am I to judge?” My hope, of course, is that the Bishop of Rome lived out his personal life in close communion with Christ, having trusted in Jesus for the salvation of his soul. If that is the case, which I have little reason to doubt, then, as is likely the case with his two predecessors, I may actually meet the man some day in the distant, or not too distant, future.

However, although I cannot judge, nor dare I, the man and his current spiritual state, I can still judge his words. And judging words, especially ones related to theological or philosophical claims, is basically what this blog is all about. Thus, my intent here is by no means to cast any aspersions about the man Jorge Mario Bergoglio, or make any proclamations about his eternal state, or even question the legitimacy of the office he held. My intent is to judge his words, the same words with which I opened this article.

Francis: The Pope Who Would Not Judge (Kind Of)

“Who am I to judge?” were likely the five words that symbolized Pope Francis’ papacy more than any others. Spoken to an Italian reporter on an airplane on July 30, 2013, just a few months into his papacy, and in response to a question about a homosexual priest, this phrase came to characterize the general tone and tenor of Francis’ pontificate. That is, however, unless Francis was speaking about conservative Catholics. When it came to conservatives, or traditionalists, Francis seemed all too eager to issue forth in judgment.

Conservatives, according to Francis, were those who have “suicidal attitudes,” who “cling to things and don’t want to see beyond them,” and who are “closed up inside dogmatic boxes.” Conservatives were, obviously, “backwards” and “ideologues.” Those interested in recapturing liturgical forms from the past, like the Latin Mass, were especially egregious in Francis’ eyes. Of course, much of Francis’ papal character might have been seen as inevitable within the Catholic Church, the liberalization of the Church post-Vatican II being decried by many for roughly three generations.

And so here was a potential champion for the overall cause of liberalization. Francis, unlike his predecessors, could be the catalyst for the “updating” aspect of the “aggiornamento-ressourcement” dynamic that issued forth from Vatican II. A man with the right kind of pedigree: a South American Bishop who emerged from an intellectual milieu steeped in Christo-Marxist Liberation Theology, and a Jesuit. As such, what became noticeable over Francis’ tenure as Pope was that the backwardness of conservatives, both inside and outside the church, related mainly to anthropological issues: primarily ones concerning sex and gender, but also climate change, immigration and, as per usual, capitalism. But apart from these particular issues, something more was going on in Francis’ reign as Pontiff–something of a higher philosophical and theological order.

Writing in the wake of the 2023 Synod on Synodality and the controversial declaration Fiducia Supplicans, Catholic journalist Michael Sean Winters wrote:

The shift Francis intends is, at once, less exact and more profound than a doctrinal shift. What Francis has been trying to achieve for many years is to relocate the place of doctrine within the magisterium of the church, specifically to insist that doctrine serve the good of souls, not the other way round.

Instead of seeing the pope’s responsibility as confined to the articulation of clearly thought-out statements of what the church does and does not believe, Francis wants the teaching office to prioritize its own pastoral application above doctrinal clarity. “How will this affect real people?” Francis asks before he puts pen to paper.

This analysis by Winter’s is incisive. Regardless of how one feels about Francis’ overall project as Pope, that Winter’s picks up on the crucial part of that project–a shift away from carefully articulated theological doctrine to something more experiential and contextual–is, in retrospect, rather obvious. And it is in this domain, in the domain of theological knowledge, that Francis did come off as being very non-judgmental indeed. And for conservatives, to include Evangelicals like myself, herein lie the real problem with Francis.

Francis, the vicar of Christ on earth (according to Roman Catholicism) the Supreme Pontiff between the Church and God, the Patriarch of the West, and the Prince of the Apostles was either unable or unwilling to speak clearly about issues related to divine revelation and truth. Or, at least, less willing than his predecessors. Instead the pastoral care Francis attempted to present to the world was one that called for theological and moral ambiguity. It was in this kind of doctrinal openness, or looseness, that Francis hoped to draw in those he felt conservatives, like his two predecessors, had excluded: the “real people” past dogmatists like Benedict XVI or John Paul II had apparently left behind.

Francis and the (Extended) Crisis of Modernity

Francis, of course, did not abandon in any official sense the historic teachings of the Catholic Church (with perhaps one exception). There were no major changes to the catechism under his tenure: no official recognition of same-sex marriage or affirmation of homosexual attraction, no major changes with regard to gender identity or the nature of the family, nor any alteration to doctrines on procreation and life issues (again, with maybe one exception). As authoritarian as Bergoglio may have been in his heyday as Archbishop in Buenos Aires, Francis had enough respect for the tradition and enough political savvy to know that he himself could not be that kind of change agent in Rome.

However, Francis’ enterprise of change, his progressive project could advance by other means than direct, papal fiat. In his case it was through the power of suggestion, through the downplaying of his own theological and pastoral authority and, as stated, in the downgrading of theological claims that Francis pushed his agenda forward. It was in the embrace of the crisis of modernity, the crisis of epistemic authority, that Francis could subtly move his Church away from the dogmatic pronouncements of the past, and into a new, more glorious future of religious pluralism and theological egalitarianism.

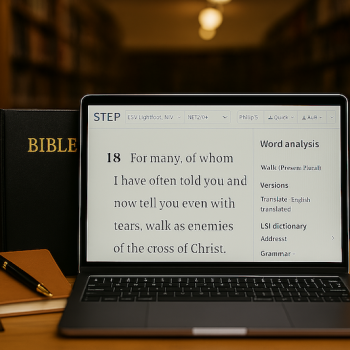

In placing pastoral care, religious experience, and moral contextualism (a hallmark of Jesuit practical theology, see Pascal’s Provincial Letters) at the fore of his ministry, Francis implicitly reduced the significance of doctrinal structure, propositional truth, and theological judgement. As such, when it came to concrete actions, like the blessing of individuals within same-sex unions, the practice could be officially endorsed by the Vatican, while the doctrine of marriage, in the books, remained untouched.

Francis, like many others affected by the teachings of Marx and Engels, understood that the concrete performance of the act itself can, and often will, eventually undermine the law-in-theory that is said to regulate it. The maxim is simple: just act as you will, then witness the law change over time. The difference between de facto and de jure mattered quite a bit in Francis’ papacy, and while liberals lauded Francis’ de facto actions, conservatives fervently appealed to the de jure formulations he neglected.

This playing around with “context” and the elevation of context over content is something that George Weigel identified in the aftermath of Fiducia, writing at the time:

Fiducia Supplicans is being presented as a genuine development in the pastoral practice of “blessing” those experiencing same-sex attraction, yet that “blessing” “does not validate or justify anything” (as Cardinal Fernández later told The Pillar). As the bishops of Cameroon noted, however, “blessing” signals approval of that-which-is-being-blessed in any linguistic context: a commonsense observation that underscores what can only be described as the sophistry of Fiducia Supplicans.

Once upon a time, and not so long ago, the dicastery charged with the defense of Catholic truth and the promotion of dynamically orthodox theology was a source of clarification. That is no longer the case. And that will be an issue during the next papal interregnum and at the next conclave.

As Weigel pointed out, it was the African Bishops, most notably Cardinal Sarah, who spoke with great moral clarity against the arbitrariness of Francis, and the elevation of act over word. Cardinal Sarah, in part, referring back to the final authority on all issues of Faith and Morals, namely, the Word of God:

“It is precisely confusion, the lack of clarity and truth and division that have disturbed and darkened this year’s Christmas celebration.”

The cardinal’s reflection, which reads like a Papal Letter, excoriates bishops who endorse Fiducia supplicans, with Sarah saying:

“They do the work of the divider….sowing doubt and scandal in the souls of the faithful by claiming to bless homosexual unions as if they were legitimate, in conformity with the nature created by God, as if they could lead to holiness and human happiness. They only generate errors, scandals, doubts and disappointments. These bishops ignore or forget the severe warning of Jesus against those who scandalize the little ones: ‘Whoever scandalizes even one of these little ones who believe in me, it is better for him to have a millstone hung around his neck and to be thrown into the depths of the sea.’ (Matt 18:6).

Thus, it was not through direct action, i.e., explicit alteration of doctrine, that Francis waged a war against tradition, and against Scripture, but through indirect action. It was the relegation of doctrine to secondary status that marked Francis papacy, and, as such, put practice before pronouncement. But the two are not meant to be sundered–theological truths existing in the abstract must find their home in concrete and context-relative application. While it is true that Jesus attacked the Pharisees for their improper application of God’s Word (“woe to you…”), he also judged the publicans and sinners according to the very same Word (“go and sin no more…”). Application without reference to the abstract and universal truths, leads to religious, moral and social experimentation: the very hallmark of the crisis of modernity, the crisis which has lead to so much cultural collapse in the West.

Conclusion: Pope Francis, A Man of His Times?

“Who am I to judge?” In one sense Francis was right. No one, not even the Pope, can judge the status of another’s soul. Only God has that kind of knowledge. However, when it comes to making theological judgements, and articulating those judgements clearly, Francis was a man of his times. That said, we should remember that those times were the 1960s and 1970s. At 88, Bergoglio was shaped by the post-modernism of his formative years. Truth, we were told after the crises of modernity, was relative to the individual. All judgements were provisional, and morality was based mainly on affections. For Francis, this was the Zeitgeist that shaped his philosophical and theological approach and stained his papal regency.

However, recent evidence in many, if not most, domains of culture suggest that the era of post-modern relativism has passed. The old mantra of “you have your truth, I have mine” has been replaced by cancel culture, campus protest, and shadow banning. The “casual relativism” of Francis’ era is being replaced by the strong voice of authority, even of authoritarianism. In a recent dialogue on Glenn Loury’s podcast, friends and colleagues Cornel West and Robert P. George both lamented the authoritarian ideology that has dominated American universities for over two decades now. Authority is making a comeback, regardless of whether it is bolstered by reasoned arguments and evidence or not.

Behind the scenes Jorge Mario Bergoglio was not as soft and squishy as many made him out to be, like this early documentary about his burgeoning papacy. Francis was certainly dogmatic in his own way, and with respect to his own agenda. However, in failing to act authoritatively where it matters most for a Supreme Pontiff, on issues of theological dogma (a term that desperately needs to be reclaimed for the good), Francis, unlike his predecessors, failed to stand as a bulwark of faith against the shifting tides of culture. And, in this sense, Francis was much more a man of his times than a man for all seasons.