July 4th always brings me back to Boston. In most cases, it is because I am revisiting my homeland to celebrate the only proper way: with the music of the Boston Pops and the 1812 Overture (even if last year it was only on Bloomberg TV). But even when I’m not in Boston (and I have spent July 4th everywhere from London to Ohio), I think of Boston.

Boston is a special place for literature and an especially sacred place for American poetry. In the eighteenth-century, Boston housed one of the most famous global literary celebrities, Phyllis Wheatley (1753-1784). She was born in Africa, sold into slavery in childhood, and by the age of twenty was one of the first American literary superstars. Her collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) is a classic.

Reading the collection, one is struck by how much Wheatley has mastered European poetic conventions and brought them to America. Her expertise in classical literature and the swollen phrases of John Dryden, Alexander Pope, and their ilk drip from every page.

Readers in 1773 would have read a preface detailing Wheatley’s extraordinary life. She was brought to America and enslaved as a young girl. It took her sixteen months to learn to speak English and only a year or two after that she wrote an impressive formal letter to the Reverend Occom, a minister to the Native American population, while she was in England in 1765. By 1773, having mastered the writing of English, she was deep in the study of Latin. Her prodigious mind was the talk of Boston.

If you know just one poem by Wheatley, it is most likely “On Being Brought from Africa to America”:

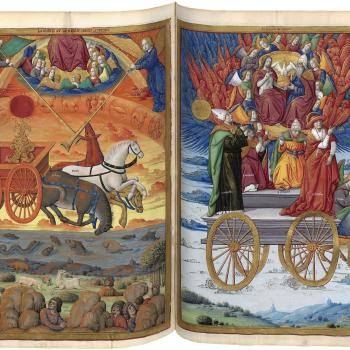

O could I rival thine and Virgil’s page,

Or claim the Muses with the Mantuan Sage;

Soon the same beauties should my mind adorn,

And the same ardors in my soul should burn:

Then should my song in bolder notes arise,

And all my numbers pleasingly surprise;

But here I sit, and mourn a grov’ling mind,

That fain would mount, and ride upon the wind.

Not you, my friend, these plaintive strains become,

Not you, whose bosom is the Muses home;

When they from tow’ring Helicon retire,

They fan in you the bright immortal fire,

But I less happy, cannot raise the song,

The fault’ring music dies upon my tongue.

The happier Terence all the choir inspir’d,

His soul replenish’d, and his bosom fir’d;

But say, ye Muses, why this partial grace,

To one alone of Afric’s sable race;

From age to age transmitting thus his name

With the finest glory in the rolls of fame?

Thy virtues, great Maecenas! shall be sung

In praise of him, from whom those virtues sprung:

While blooming wreaths around thy temples spread,

I’ll snatch a laurel from thine honour’d head,

While you indulgent smile upon the deed.

As long as Thames in streams majestic flows,

Or Naiads in their oozy beds repose

While Phoebus reigns above the starry train

While bright Aurora purples o’er the main,

So long, great Sir, the muse thy praise shall sing,

So long thy praise shal’ make Parnassus ring:

Then grant, Maecenas, thy paternal rays,

Hear me propitious, and defend my lays.

Wheatley sees the one famous African poet whose name has survived on European and American lips: Terence. While she engages in some of the symbolic modesty essential for this sort of poem, it is clear she has hopes to pick up where Terence left off. In many ways, she succeeded. Sadly, her life also resembles his. After being freed by her master shortly after the publication of her book, she found herself in poverty, unable to publish again, and suffering the death of her children from illness. She would die young too, at 31. Like so many freed slaves whose past lives in slavery had featured creative work in the proximity of high society, life after slavery was often hard and full of thankless work and poverty. Jefferson’s own cook, James Hemings, freed later in his life, ended his days in poverty and alcoholism before committing suicide. The human dignity of freedom, a rare gift to slaves in those days before Emancipation, came with a cost in a society built on racial hatred and segregation.

Though Wheatley’s extraordinary life is an American story, it is also a testament to a legacy of American cruelty and to the way the sin and idol of racism have destroyed the lives and talents of generations. Wheatley’s work is a miracle shining out from a shameful period. On July 4, we should think of these American stories. Stories of cruelty. Stories of defiant strength. Stories that remind us we can become better, that we need to become better, starting now.