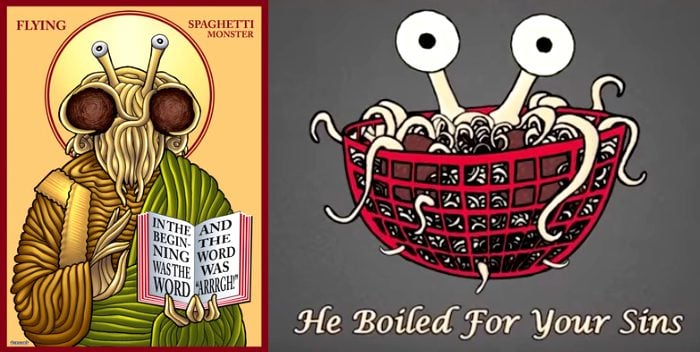

LET’S face it: Pastafarianism is as credible as any other religion, so it’s a crying shame that it can’t get official recognition in Australia.

The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s latest bid for legal status as an incorporated entity – spearheaded by Tanya Watkins, a self-described “captain” of the church – has been tossed by the South Australian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (SACAT), which declared Pastafarianism a “hoax” despite it having having a “holy tome” that sets out its basic tenets.

The Gospel of The Flying Spaghetti Monster includes a creation myth, just like the Bible does, has guide to evangelising, and discusses history and lifestyle from a Pastafarian perspective.

After recognition was denied by the Corporate Affairs Commission, Watkins sought a review of that decision, and the matter was subsequently referred to SACAT.

The tribunal heard evidence from the Commission and from Watkins, who contended that the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster was formed for a “religious, educational, charitable or benevolent purpose”, thereby meeting the criteria of South Australia’s Associations Incorporation Act.

Watkins told the tribunal the church placed emphasis on helping others, and had engaged in acts of charity such as an event at Flinders University to “feed the hungry”.

In a ruling handed down earlier this year, and recently published online, SACAT Senior Member Kathleen McEvoy rejected the arguments for incorporation, saying:

Ms Watkins explained to the tribunal that she was seeking incorporation for the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster Australia in order that the association would be recognised as a not for profit organisation under the Act, and be a legal entity in its own right.

McEvoy noted that while various “Pastafarian texts” are set out in traditional religious forms, they “contain some surprising articulations”, such as references to the books of the Bible as the “Old Testicle” and “New Testicle”.

In particular there are numerous expressions which reference the texts of established religions, mimicking those texts in form and language, but in a clearly parodic form.

I do not accept the applicant’s explanation of the use of these expressions (and numerous other similar expressions, many expressed in racist and sexist terms, referencing texts or practices of other religions) as examples of humour, and for the purpose of generating curiosity.

Racism and sexism? Has McEvoy ever read the Bible? Or the Koran, for that matter?

It is my view that the Pastafarian texts can only be read as parody or satire, namely, an imitation of work made for comic effect. In my view, its purpose is to satirise or mock established religions, and it does so without discrimination.

McEvoy upheld the Corporate Affairs Commission’s decision that there was no evidence the church engaged in:

Systematic teaching and learning processes, nor of any structured, consistent, and broad-based charitable activities. I am satisfied that the proposed incorporated association merely presents as having a religious purpose, but is a sham religion or a parody of religion.

It was not formed for a religious purpose. On this basis, to conclude it is eligible for incorporation as a body with a religious purpose could clearly not be a preferable decision.

Watkins said she found SACAT’s decision “quite disappointing”, and said incorporation would have brought considerable benefits.

If you’ve got an association, then you should get it incorporated because then you’ve got government oversight, you can run a bank account and all those sorts of things so we could be transparent and above board.

She rejected claims that the church was a “sham” and a “hoax”, which she said came:

From a misunderstanding. You’ll find that there is a core group of people who really believe in Pastafarianism and that it can change people’s lives for the better. Satire does have a serious purpose, because satire makes people think.

In Poland, of all places, Pastafarians successfully sued the government in 2014 after it was refused recognition as an official religion. Naturally, the country’s large right-wing Catholic population was horrified.

Two years later The Netherlands granted the church recognition and so did New Zealand.

There a 15-old old student complained to a the NZ Human Rights Commission after he was refused permission to wear a sacred symbol of his faith on his head – a bright red colander.

I’d love a cup of coffee

I’d love a cup of coffee