by guest writer Gregory Moomjy

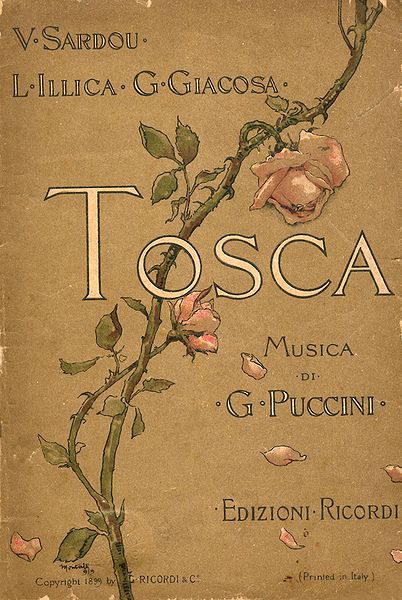

As an opera lover, I know how easy it is to make fun of operatic tropes. Perhaps none is easier to lampoon than that of the put-upon soprano dying for love in the end. To be sure, there are many operas where this is the case. Unfortunately, tropes have a way of dampening the gravitas of their subject matter. And Puccini’s Tosca (1900) has fallen victim to this pattern.

Tosca is a unique opera in that it is a fictional story that takes place in actual locations. It is set in Rome in 1800 as the city reacts to the liberalization of the French Revolution, symbolized by Napoleon—a growing power, who is threatening to conquer Italy. Two of the opera’s main characters, Tosca and Scarpia, serve as foils of each other in their religious identities. Tosca—an opera singer—is devout, with her views of religion intrinsic to her being. By contrast, Scarpia—a police chief—is someone who uses religion to get what he wants, typically in the form of sexual conquest.

Tosca belongs to the Verismo school of opera, a tradition of realism in opera that was popular at the turn of the 20th century. It aimed to eschew the nobility and mythological characters of previous works, in favor of everyday characters having relatable reactions to quotidian situations. In the past, when operas dealt with personal relationships with God, many of the characters were martyrs or people who at least were outwardly okay with enduring hardship and dying for their faith. In this opera, we see a layperson of faith who struggles with her beliefs in real-time. Puccini’s Tosca is an examination of how an ordinary person’s relationship with God can change under duress, and even become more profound.

When Tosca first appears in Act I, she arrives at church to pray. However, she does not realize that this house of prayer has become the setting of illegal revolutionary activity, involving her lover—the painter and pro-Napoleon activist, Mario Cavaradossi. Baron Scarpia, the chief of police, soon arrives. He is the opera’s symbol of Italy’s repressive reactionary politics. He decides to make Tosca a pawn in his political and sexual games.

He preys on Tosca, insinuating that Mario was in the church previously for a sexual rendezvous, hoping to illicit jealousy. What is interesting is not what he says, but how he says it. He first draws Tosca in by offering her holy water, then implying how nice it is to see a woman in church who is genuinely devout, as opposed to other women who—in the vein of Mary Magdalene—come to church for love. At this point, Scarpia clearly wants to draw a wedge between Tosca and her lover, but interestingly chooses biblical imagery to do so. This gives credence to a previous remark of Cavaradossi’s, that Scarpia uses religion for his own wicked purposes.

Church bells can be heard from the beginning of Scarpia and Tosca’s duet, from when he offers her holy water, to the end of the act. Puccini was influenced by both Wagner and Verdi. To that end, the bells are both a kind of tinta and leitmotif symbolizing Scarpia’s use of religion for nefarious purposes. Tosca’s tinta puts the action squarely in Napoleonic-Rome. Puccini was very interested to know the exact sound of the church bells in Rome, specifically Sant’Andrea della Valle—Act I’s setting.

As congregants gather for mass, Puccini desired the chorus to intentionally mispronounce their Latin. He was not as interested in the meaning of the Latin text as he was in creating a kind of seedy, evil-sounding Latin that heightens Scarpia’s corruption. Scarpia and Tosca have the most overtly religious pieces in the opera. Tosca’s Act II aria, “Vissi D’arte,” is an outright prayer. Scarpia’s “Te Deum”—a Latin hymn—at the end of Act I is a kind of backwards liturgical piece, like Iago’s Credo in Otello. In this case, as the crowd gathers for mass, Scarpia prays that he will be able to send Tosca’s prorevolutionary lover to his execution, and defile Tosca.

Tosca is a thriller set over the course of a day. The woman we see at the end of the opera is quite different from who meet in the beginning. The first thing Tosca does is arrive at church to pray and offer flowers to The Virgin Mary. Victorien Sardou’s 1887 play “La Tosca,” on which the opera is based, goes into more detail on Tosca’s childhood: she was an orphan taken in by Benedictine nuns, and she maintains strong religious beliefs since childhood. Certain singers have noted that Tosca’s premarital intimacy with Cavaradossi in contrast to her religious upbringing is the reason for her need to atone in church.

In Act II, at a performance at the royal palace, Scarpia invites Tosca to his dining room. He propositions her, after revealing that he is torturing Cavaradossi in the next room. When she thwarts his advances, Scarpia resorts to an ultimatum. Snare drums cue marching in the street below. Telling Tosca that this is the march of a dead man, Scarpia informs her that Cavaradossi will die unless she succumbs to his advances. The action comes to a dead stop for “Vissi D’arte,” Tosca’s prayer and the only aria in Act II. Soprano, Sondra Radvanovsky—well-known for her portrayal of Tosca—said of the aria (in an interview with WNYC Studios “Aria Code”): “She calls [God] ‘signor,’ not Dio, but more informal… And that’s how Tosca always talked to God… Because she prayed to God… every day.” She addresses him intimately and frankly, reminding God of her devotion, in contrast to her current misfortune.

Tosca accepts Scarpia’s advances, in exchange for Cavaradossi’s life—he is to be shot instead of hanged, but with blanks. Tosca has unwittingly been tricked and Mario is still going to die. But at the last moment, she discovers a knife and stabs Scarpia. The visual history of Tosca is very much steeped in tradition, many of which come from the play. Much of what the actress, Sarah Bernhardt—a famous interpreter of Tosca—did in the play was carried into the opera, specifically how Tosca murders Scarpia. She was the first to arrange candles around Scarpia’s corpse, in the shape of a cross, as a way of expiating the sin of murder.

No matter how you stage the end of Act II, Tosca’s first words immediately after Scarpia dies are “he is dead! Now I forgive him!” There is still a sense of Tosca maintaining a deeply religious core, even after committing murder, though it is shifted or hardened by her defending herself. The ending of the opera in Act III shows just how much Tosca has changed. As Tosca realizes Scarpia’s deception, police come to arrest her, having discovered Scarpia’s body. Rather than face arrest, she leaps to her death from the castle walls, calling out and commanding Scarpia to wait for her before God.

That last line of the opera clearly shows she does not die for love, as many believe. Rather, to preserve her human dignity. Yet she still wants justice, and to personally witness Scarpia’s divine retribution. It is telling that she voluntarily commits suicide—a mortal sin for a religious Catholic. In theological terms, she is risking becoming irredeemable in the presence of God. Therefore, her relationship with God has clearly changed and become more nuanced. No longer does she strictly follow religious dictates, but rather shapes her own relationship with God. It is more human, more believable, and definitely Verismo.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tosca_libretto_cover.jpg