As I load the car, like millions of other Americans, for a long road trip to see family this week, I find myself contemplating a theological reclaiming of Thanksgiving.

Holy Days

All holidays were once, as is more or less obvious, “holy days.” Even as those days enter into secular civic space, the “holy” backgrounds remain part of what makes them meaningful for many people.

Thanksgiving, though, is problematic. Is there really an old holy that we are celebrating? Most of my generation grew up on the Peanuts version: children in Pilgrim and Indian costumes drawing hand turkeys. I find the Peanuts Thanksgiving special of 1973, by the way, to be a mere shadow of the theological brilliance of both “The Great Pumpkin” (1966) and “Charlie Brown Christmas” (1965).

But I say we need a reclaiming because the problem with this particular holiday isn’t, actually, a lack of theological origin. Rather, it’s that the theology is mostly bad.

The First Theology of Thanksgiving

The seafarers aboard the Mayflower were Puritans and Separatists whom we began calling “The Pilgrims” 200 years after the fact. The journey itself was theological in nature. These early Protestants—Catholics of the time had other problems—were filled with a desire to start Christianity anew. They wanted to leave behind the heaviness of tradition, culture, and authority, and find a land where they could, as the Mayflower Compact put it, govern themselves as a new society. “The Lord hath given us leave to draw our own articles,” as the Puritan John Winthrop put it ten years later. With those new articles, they would build “a city on a hill.” This faith still lives on in theologically charged language of American exceptionalism.

This dream is important not only for what they left behind, but also for what they found when they arrived. The empty expanse where they would build was of course not empty. It was thick with ancient trees and peoples. It was heavy with stories, cultures, traditions, and lines of authority. In order to carry out their Compact, the colonists would have to ignore, trample, and dishonor all of this. It didn’t fit with their theology.

The history of the relations of the colonies with the Native Peoples is one we should probably just drop pretences around and call a genocide. And the hope in traditionless, cultureless expanses in which to build a beacon of Christianity is the theology that supported the genocide.

Escaping Tradition

This desire for a reboot was an epidemic of the era that went beyond theology. It was a part of the new way of thinking in a Europe that was emerging from the Middle Ages. In fact, the very term “Middle Ages” was one the people of this time invented as a way of dismissing the thought, traditions, and culture of the previous 1000 years. They spoke of a return to primitive Christianity, celebrated a literary humanism that turned to the ancient Greeks, and eventually built a neo-classical revival in architecture. It was an era of renaissance: rebirth. And those Pilgrims were aiming to be reborn as far away from their old lives and customs as possible.

It’s one thing to negotiate one’s way into problematic traditions. All traditions, all cultures, are problematic. Few of us do things exactly like our grandparents did. Rather, at best, we allow those traditions to form us while we’re young, and then gradually we learn to engage with them critically. We revise, accept, and discard various aspects of the worlds that formed us. It’s a bit like a work of improvisational theater: we find our way into being ourselves through the language and structures others have offered us.

It’s another thing entirely, though, to reject a tradition from soup to nuts. This is often, as I think was the case with our Pilgrims, a recipe for hubris. It’s a people saying “We have moved so far beyond our ancestors and fellow humans that we need a big blank space, free of them, in order to start over.” There are, to be sure, moments of real beauty and insight to the undecorated language and worship spaces of these Christians. But the total effect is problematic: they sought to isolate themselves from all others on both sides of the Atlantic in order to hear directly from God.

Another Theological Origin Story

And yet there was a moment, there at Plymouth in 1621. After surviving their first winter and learning, from an English-speaking Pawtuxet man, how to grow corn, the colonists held a feast. They invited the Wampanoag people, who came and brought dishes to share. They celebrated soil and harvest, the changing of seasons, and the gift of cohabiting a piece of earth. It’s likely that they offered prayers of gratitude in multiple language.

It was not quite as idyllic as all that, of course. Squanto, the Pawtuxet farmer, seems to have been a survivor, not above triangulation and double talk. His own tribe, as well as the Wampanoag, had already been decimated by disease introduced by English trade ships. The alliance they formed with the Pilgrims would last half a century—an eternity in comparison with nearly every other treaty between Anglo-Americans and Native Peoples. But it would end with the bloodiest per capita war in the recorded history—still— of the continent.

Far from perfect, then. But still filled with hope and promise and joy. “We made it through the winter! The ground and forest has given us food! There are neighbors coming to share our feast! The God we trust has not forgotten us!”

I think it’s time to recover that theological origin story. Not the theology that sent the Pilgrims over here to draw their own articles. But the theology of hope and joy that the feast that day gave a small, imperfect glimpse of. A true harvest festival, where we celebrate God’s earth, its gifts, and the neighbors and family and friends with whom we share these spaces.

The Eschatological Thanksgiving

A new harvest festival would need to be an eschatologically oriented affair, as the feast of 1621 was. Not perfect, that is, but anticipating a full, divine perfection. Most often these days our connection to the earth is mediated by ecologically damaging technologies. The cranberries may come in a can from a factory, the turkey may be shipped on a truck from a giant factory farm several states away. Sometimes the neighbors and family can’t make the feast and we wind up alone.

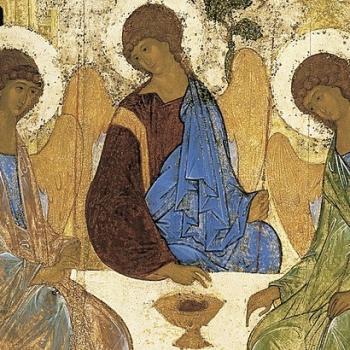

But there’s always next year, as the Jewish diaspora reminds themselves each year at their imperfect Passover. And beyond that, there’s always the feast of the Kingdom of Heaven, which all earthly harvest festivals anticipate: the “once and future” feast that we are already rehearsing for.

I hope my family Thanksgiving this year can look a little like that. A harvest festival that celebrates abundance, the changing of seasons, the gifts of soil and field, and the companionship of friends and family and strangers who navigate together our days and years on God’s good Earth.