Now they will rest before shouldering the endless work they were created to do down here in Paradise.

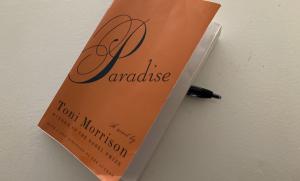

That closing line of Toni Morrison’s novel, Paradise, leaves so many questions unanswered. Not the least of which is whether the “they” of the line are real, dreams, or dreaming realities.

I don’t mean that as a critique. The late Morrison was a master of the blended realities of what she called “village literature.” Her novels imitate the oral traditions of campfire stories that neighbors might tell. Her Nobel Prize-winning tales interrogate realities we might wish were stable and beyond interrogation: race, family, and religion, primarily. And none of it in a straightforward way.

Promised Land

The late Morrison (d. 2019) was a Catholic. That matters, especially in this novel. She writes, as she puts it, about “organized religion and disorganized magic.” She consistently offers us a deep and complex view of the cosmos, and of faith in unseen powers. There is an eschatology at work in Paradise, her novel from 1997. It’s Catholic and Protestant, and charged with unsettling visions of race, family, and magic.

Paradise tells the story of a town called Ruby, located near an old Catholic convent. The convent, governed by a Brazilian-American matriarch, plays an important role in the drama that unfolds. The nearby town was founded by post-Reconstruction refugees and their descendants. Refugees who, like Israel and the Holy Family, wandered through wilderness looking for a home. Like Israel’s scripture, Ruby’s town story is sacred, but the story shifts depending on who is telling it and for what purpose. So the novel reads like fireside literature, but we listen in as if we were strangers, trying to sort out which family is which and where the power structures really lie. We’re sympathetic to the perspectives of Rev. Misner, the relatively new and rather disoriented preacher at Mount Calvary church.

We come upon the residents of Ruby in the midst of a generational debate over its motto. The founders inscribed some words on the Oven, an outdoor public gathering place. Some letters have worn off, or maybe fallen off, so that the Oven now says “The Furrow of His Brow.” The debate is over memory itself—does anyone actually recall what the whole line said? It’s also over theology: how do those words configure the town’s relation to God’s furrowed brow?

The Three Theologies of Paradise

Beware the Furrow

The older men of the town insist the missing word is “Beware.” The key spokesman is Reverend Pulliam of the New Zion church. “God’s justice is God’s alone,” he tells them. Our role is to obey. “That’s not a suggestion, it’s an order!”

The irony of Pulliam’s theology—let’s call it vertical revelation, straight down from God—is that this dehumanizing of justice amounts to an uncritical divinization. Certain men—sons of the founding families—become the gods of the town. This is never more evident than in the harrowing climax, when they shoo the youth away from the Oven so they can plan their great act of violent brow-furrowing.

But the irony seems lost to Reverend Pulliam. He preaches an impromptu sermon at a town wedding and tells them that love, like justice, has nothing to do with human feelings or bodies. “It is a learned application without reason or motive except that it is God.” You don’t share it in, and there are no epiphanies of experience. You practice obedience, and so learn and earn God. “Love is not a gift. It is a diploma.”

Be the Furrow

The young people of the town have been paying attention to the Civil Rights leaders and the movement for justice that comes through marches and protests. Perhaps, they suggest, the original words said “Be the furrow of His brow.”

Their spokesman is Reverend Misner, that recent arrival I mentioned. Or rather, he is their non-spokesman. Misner organizes the youth but says little. Still, he is Pulliam’s target. Pulliam is attempting to crush Misner’s notion of “God as a permanent interior engine that, once ignited, roared, purred, and moved inside you to do your own work as well as His.”

When Misner rises to respond at the wedding, he has no words. Instead, he walks to the back of the church, takes the cross off the wall, and walks back up to the platform. For several minutes, he simply holds it aloft in awkward silence. (What a wedding this is turning out to be!)

For Misner, the cross is the figure not of a bloody sacrifice, but of “a human figure poised to embrace.” Here the typical Protestant empty cross is important for the symbolism. The wood beams themselves make a stick figure: Christianity is an a love-empowered humanism. There, in the horizontal crossbeams, is God’s embrace of all human embodiment. Even more, God’s remainder-less presence as that embrace. It’s in lateral human effort, not waiting on vertical drops, that we meet God. God is you: this is what Misner wanted them to see.

Furrow

The third theology is subtle. We first get a hint of it from Dovey, the wife of one of the great men of the city.

Beware the Furrow of his Brow? Be the Furrow of His Brow?” Her own opinion was that “Furrow of His Brow” alone was enough for any age or generation. Specifying it, particularizing it, nailing its meaning down, was futile.

The “preacher” of this theology is not in fact the town’s third minister, whose role is minimal, but the midwife, whom we meet late in the narrative. Lone DuPres exists in the middle space between “Be” and “Beware.” She also exists somewhere on the spectrum between Christian doctrine and Afrocarribean magic. She uses her ears and her ingenuity, all the time chanting the mantra “Thy will, thy will.” God does not “thunder instruction or whisper messages into ears. Oh, no,” she reminds herself. God liberates from beyond but also through us. Something like “a teacher who taught you how to learn, to see for yourself.”

Lone, I suspect, is very close to Morrison’s own theological voice. Perhaps she would forgive me for calling it a diagonal? God’s will is vertically beyond us, but we only approach it by moving forward in lateral acts of creativity.

Making the Gift of Paradise

Look back again at that closing line. Do you see the disorienting directionality of it? Is paradise something up above us, or something down here? And what about that “created to do?” That’s a passive verb, which means the subject is not the agent, but someone else is. But we’re still agents, doing the work. Morrison has got us in a complex spot here. It’s what grammarians (and some theologians!) call the middle voice. It’s a kind of active reception.

Morrison tells us that she is attempting here to knock paradise off its pedestal. That might lead us to think that she is a Reverend Misner, telling us that our vision of an eschatologically beloved community is what we make of it. But that is exactly the equalizing irony that she wants to show us a way beyond. A paradise that comes only from below (“Be”) remains flawed. One that comes only from beyond (“Beware”) ultimately fashions itself as a humanly willed, and thoroughly ruined, community (“Be”). There is no difference, really, between Pulliam’s and Misner’s eschatology. Only the middle space of a received and paradoxical charge—created to create—escapes this dilemma.

Paradise, for Morrison, is the Creator’s gift that we were created to make.