OK Christmas, can we talk about the Virgin Birth?

OK Christmas, can we talk about the Virgin Birth?

After our recent Advent service of Lessons and Carols at Saint Julian of Norwich Episcopal Church, my friend Robbie asked me these questions:

- Is it necessary for Mary to have been a virgin to have been anointed by God to carry his child?

- Could this part of the story be another example in our patriarchal history of subjugating women?

Could the Virgin Birth Be about Subjugating Women?

I’ll start with that last question. Yes, it could. Angela Franks over at the Church Life Journal recently wrote a bit about this topic. She laid out a good theological defense against a feminist rejection of Mary’s poverty, including the bodily poverty of virginity. Still, I’m just Protestant enough, and just feminist enough, to note the risks here.

It’s possible to see Mary’s example as a demonization of female sexuality. I mean that alarming abstract noun, demonization, literally. The Catholic dogma, or teaching taken as divinely revealed, of Immaculate Conception holds that Mary was the first human born without original sin. (Jesus was the second; Adam and Eve were formed, but not born, without original sin). Sloppy theology might connect this belief too immediately to another of the four Marian Dogmas, the Perpetual Virginity. This mistake would identify her avoidance of sex as a sign of her sinlessness. It would, reciprocally, suggest that a life of sexual fulfillment is a life of sin. This is a patriarchal warping of the Incarnation story. No one has ever cared, so far as I’m aware, about whether Joseph went through life as a virgin.

The Trouble with Marian Dogmas

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I think there’s something excessive and theologically distracting about the dogma of the Immaculate Conception. Russian theologian Sergei Bulgakov is on my side. He sees a risk here of sterilizing the act by which God enters the world in Christ. In my language (which I’ve also adapted from Bulgakov), the theology of the Immaculate Conception isn’t diagonal enough. The point about Jesus is that God humbles Godself so much as to be born through the will of a faithful human who bears the weight of sin and death. I think the Immaculate Conception exalts the person of Mary, which is a good thing. But I think it does so by missing an important facet of the Incarnation, which is a bad thing.

Something similar could be said of the Perpetual Virginity. It is an excessive Dogma that celebrates the wrong thing. The Virgin Birth—I’ll say more about this in a moment—is a doctrine about Christ’s identity. If it’s about the ongoing life of Mary after Bethlehem, it becomes less about Jesus, and more about the sex she didn’t have. And then we’re back to a misogynistic model of the feminine: woman as sexless birth-mother. The model that literally no one else can live up to. (Barring technological intervention, I suppose. A topic about which Catholic Social Teaching has a thing or two to say.)

The way to challenge what I’m saying here is to note the theologically rich literature on celibacy. I’ll save that for later, and simply note that if Mary’s perpetual virginity is a model of the vowed celibate rather than the ideal woman, this is a good thing. Still, by elevating it to one of four Marian Dogmas the Roman Catholic theology is, I think, excessive.

The Fittingness of the Virgin Birth

This brings me finally to my friend Robbie’s initial question, about the theological necessity of the Virgin Birth. I’ll answer this one simply as well: no, it is not necessary for Mary to have been a virgin. It is not necessary, even, for God to have been Incarnate in Christ. The work of salvation could have happened in other ways. The story could have taken a thousand different shapes.

But this is the story we have. Thomas Aquinas’s theological category for this is “fittingness.” It is not necessary that God be born of a virgin, but it fits. That’s what Matthew is noting, as I said last week, when he finds the pattern of the Bethlehem story in Isaiah’s prophecy.

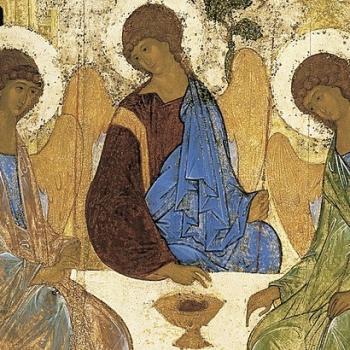

It fits because, again, the story is about Jesus before it’s about Mary. Mary is God-bearer: that’s the one Catholic Marian Dogma we can’t do without. The one born from her is not a human who one day gets deified. That’s the heresy of adoptionism. Rather, her son is as fully human as she is, and also as fully divine as his Father in heaven.

The Excessiveness of the Virgin Birth

I’ve challenged excessive Mariology above. But the Virgin Birth is also excessive. It’s just, I would say, excessive in a way that fits. Luke wants us to know that Mary’s conception of Jesus is like Sarai’s conception of Isaac and Hannah’s of Samuel, but even more dependent on God’s agency. So Luke pairs the story of Mary the Virgin Mother with Elizabeth the Post-Menopausal Mother. Elizabeth is the barren and aged one—Hannah and Sarai joined in one. Hers is the miracle of a infertile womb bearing a child.

But Mary? Mary’s miracle is a Virgin Birth. In her, as Karl Barth pithily put it, “the inconceivable is conceived.” The divine act in Elizabeth’s body prepares the way, as her son will prepare the way, for what God does in Mary. Mary doesn’t abolish, but fulfills—as her son will fulfill—the history of God’s miraculous acts in Israel.

The Virgin Birth is the miracle of God’s involvement with human life turned all the way up to eleven. God could have saved the world without it. And it rides the edge of misogyny. But handled with care, it can open our eyes to the beautiful story of the God-bearer and the God she bore.

Do you, like, Robbie, have questions you’d like to see me struggle with in this column? Send me a note on Facebook or Twitter.