Thought and Song

When revivalists—traveling preachers— would come to my childhood church for a special series of weekend services, they would always come with a song evangelist. The implication I suppose was that singing was as much a part of reviving our souls as was hearing the words of the Bible interpreted to us in a sermon. My dad would get annoyed when the singer would hold out a high note for a long time in an effort to get the crowd to start shouting. “Does the Spirit like the high notes better?” I remember him asking. Augustine, incidentally, also worried about music’s ability to manipulate crowds. It could circumvent thought, and that made him suspicious. He had a point. So does my dad.

Music can manipulate. At the same time, though, music can also elevate. It can invite us through a door that we don’t have access to cerebrally. Or only cerebrally, maybe I should say. The Black preachers that I spent time around in my childhood had the ability to make music out of a sermon. They found the place where thought turned to song. The Reverend Ruben C. Fields of the Ravensbrook Widow Missionary Baptist Bible Church could turn from sermon to song within a single sentence.

Music lives in the body in a special way, which is why even this reserved white boy from Indiana can sometimes feel an inexplicable need to dance. You don’t necessarily want to be there when it happens. But it happens.

Thinking with a Psalm

When we chant the Psalms in my Episcopal seminary chapel, we’re a long way from Rev. Fields’s pulpit, or from the song evangelists that would lead us through Bill Gaither’s hymns. Anglican chant is a simple way of putting text into a repeated tune. It can focus the attention while it also aids the memory. The words that I otherwise would just read or hear read are now in my body. They’ll likely show up in my memory later in the day.

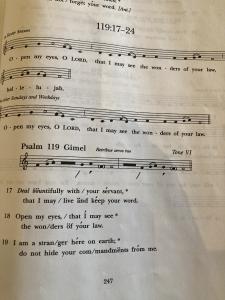

We recently chanted a portion of Psalm 119, the third or “Gimel” stanza, if you’re following the Hebrew alphabet through the acrostic of the long Psalm. (By the way, can you imagine 26 verses of “Just As I Am”?). Like the rest of 119, these verses address the deep trust and love that the singer has for Torah. Verse 18 asks for the vision that will inspire such love and trust, suggesting helpfully that it doesn’t come naturally. “Open my eyes, that I may see the wonders of your law.”

It’s a lovely and rich line. It’s one that can undo a good bit of my own pre-judgments about what law, including Jewish Law, is. I think of law as binding, restricting, and sometimes oppressing. I live in Texas, where the legal codes have gone through more revision and include more riders than I think anyone knows, let alone can follow. And Leviticus seems not far behind, with its catalogue of commandment after commandment about diets and sex and farming.

So it’s a good surprise for me to read that there are wonders of Torah that are of an entirely different order than what I’m imagining when I hear the word “law.” But here’s the thing: I’m coming into chapel a little distracted, and it’s likely going to take more than a spoken phrase to catch my attention. I might pray “Open my eyes,” but do so without ever noticing what I’m saying, and so go on with eyes shut and miss the prayer and the wonder.

Singing a Psalm

That’s where the chanting does some work. The tonal setting we put it to that day ascends up a small scale in the first syllables, so that by the time we got to “eyes,” we’d heard our voices rise a step and a half. I actually felt my chin lifting as I walked up the notes. When I noticed this, something odd happened. Psalm 121 also flashed into my memory, even as we worked on 119. “I lift up my eyes to the hills.” In lifting my voice, I’d actually lifted my chin and eyes, and so doubled the metaphor with the two Psalms. My downcast eyes turned up to the hills; my eyes too shut to see the wonders of Torah began to open.

As it happened, that week my mom had sent me Psalm 121 in a text, which is likely why it was in my mind. So as my chin and voice lifted, I also had a flashing vision of Mom, sitting with her Bible and a cup of morning coffee. My mom’s prayers, the Psalmist looking up toward hills, the opening of squinted eyelids: all that rhymed, you might say, within the poetry of the prayer. And the source of the rhyme was song itself.

Delight in God’s Law

C. S. Lewis once said that the greatest gift of the Psalter, for him, was the invitation to delight in God. Delight is unchecked pleasure, and, like wonder, it’s often not a thing that comes through thought alone. Psalm 119 connects it directly to musical imagery. “I find my delight in your commandments, because I love them” (119:47); “Your statues have been my song wherever I make my home” (119:54). The wonders of Torah fill the Psalmist with delight. When Lewis paid attention to this musical delight, he found himself tempted to take up song and dance. Lewis was an even more reserved white boy than I am, so that takes some doing.

Singing these ancient hymns anew in chapel that day, I suppose I started to feel the Spirit, as those evangelists of my childhood would have put it. I noticed something happening in my mind and my body as I chanted, and also now as I reflect on it all. I remembered Mom, I remembered Rev. Fields, I remembered the occasionally manipulative way those tenors would hold the high note while the musicians sat and waited for them to run out of breath. And all of that musical feeling, complex as it is, reminds me of the wonders of Torah. It fills me with a tiny bit of the delight that God was hoping for when God gave us the gift of a wonder-filled, musical, Law.