Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Wind shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming (1919)

The Truth Beneath the Lie

Everyone remembers how Steve Bannon douche-slouched his way into the Trump White House for the first time, like the hitchhiking epiphenomena of a brain tumor. They were our Bobbsey Twins, Bannon and Trump. Our post-millennial and post-modern, inverted and psychotic, parody of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s own half-demented claim that electing Bill meant getting “two [presidents] for the price of one.” We got Steve and Donald, that crazy Odd Couple. Not Oscar Madison and Felix Unger. Perhaps closer to Oscar Madison and Oscar the Grouch.

From the outset, Bannon was a malignancy upon his own cancerous host, a Chief Presidential Strategist carcinoma feeding upon the Presidential Brain Tumor in the Oval Office. A cancer squared. Amidst this chaos, it is now difficult to remember that Bannon was the one who provided clarity, who not only spoke his mind, but who absolutely meant what he said.

In this sense, Bannon personified the underpinnings, the justifications for what was to come, the twisted allure for so many of this putrid White House seep, this not-quite-movement conservatism upon which Donald Trump rose to power like a toad upon a geyser. Bannon was, in that moment, the only way we had to steer clear of the emotional chaos activated by extrusions of Donald Trump’s fevered mind – incessant social media chatter, tabloid focus on personalities, shattered boundaries between personal and professional, a looming collective, paranoid psychosis.

Consider the impression left upon the grass after someone (Trump perhaps), surreptitiously, when he thinks no one is looking, pokes a golf ball closer to the pin. Then consider Steve Bannon in the White House, the truth beneath the lie.

What follows is, by design and by necessity, an impressionistic rendering of the ideological landscape of American movement conservatism. There is nothing tidy or organized or logical or structured about this political movement. Journalists have spoken of the movement’s “intellectual source code,” and that is an apt and clever phrase, but as source code goes, it is bug-ridden and messy, potted with security holes, loaded with traps and loops. Given the mess, there is no real way to traverse or map this landscape of ideas without approaching it, and imagining it, as a whole that is far less than the sum of its parts. But the parts themselves – fragments and shards of ideas and impulses – are each in their own way fascinating and revealing and deserving of scrutiny on their own terms.

We must begin, then, with Steve Bannon, Dark Enlightenment Sith Lord, whose ideas and influence provide the single most coherent philosophical basis for considering the benighted path on which we now travel.

Gothic Moment

In “normal” times, politically, or at least in our schoolbook “consensus,” “pluralist,” or “interest group” images of politics, the center holds because ultimately it is in the interest of politicians, and political parties, and the organizations and groups and populations they represent, to compromise, take half a loaf, that they may live to fight another day. The premise of pluralism is that people are pragmatic, not idealistic, and that bargaining and deal-making can hold together the nation because most people are fundamentally alike, at least in the sense that they speak the same language and can build trust around their understanding of what words mean and how they represent the world, at least that part of it which is up for grabs. These notions are the mother’s milk of our citizen identity, reinforced historically and culturally through our political and civic associations (including media), common law traditions, and Enlightenment values (see Alexis de Tocqueville, Louis Hartz, etc.).

The strength (and weakness) of these political habits and beliefs is that they are process-driven, not outcome-driven. We associate Enlightenment ideals of representative democracy, individual freedom, legal equality, and political justice with rule-driven attributes and standards of process fairness, consistency, and coherence. The container matters more than the content. Whether naïve or not, this liberal political culture owes an enormous amount to the historically specific claims of the Enlightenment, in combination with English common law traditions, on the American founders.

When you read The Federalist, despite the significant and meaningful differences in the political visions of Madison and Hamilton, and between the Federalists and the Antifederalists, all parties communicate a deeply rooted commitment to the shared identity of humans bound together and lifted up by a capacity to reason, employ logic, deduce consequences, gather evidence, and share knowledge. Baseline commitments to process (and progress) within our political culture depend on the Enlightenment assumption of epistemic coherence, that knowledge about the world objectively exists, and that we can discover and share this knowledge with each other.

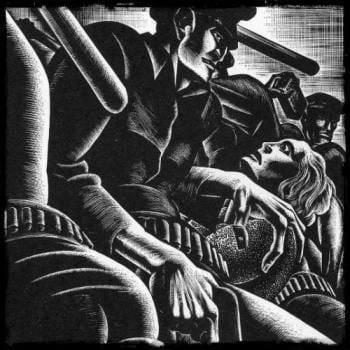

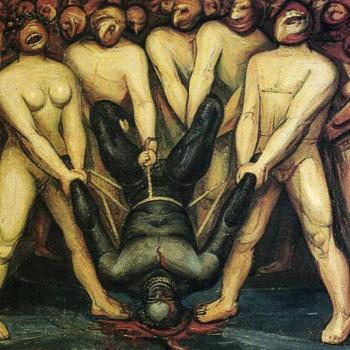

The problem is that when we experience abnormal or disjunctive political moments – such as 9/11 or Hurricane Katrina or Wall Street run amok – we discover the process coefficient breaks down and epistemic incoherence ensues. We become strangers to each other. Irruptions from below disclose a chaotic, Bosch-like underworld that disputes almost every dimension of the reality our political institutions take for granted and require – that our votes matter, that our efforts matter, that science matters, that government helps us more than it harms us, that media seeks and tells the truth.

In those moments, unfairly disproportionate or unexpectedly unequal social outcomes shred the process container, and in the chaos that ensues we experience not simply the frailty of our political institutions, but the extent to which the rational Enlightenment vision on which they depend remains inaccessible and alien and threatening and illegitimate to vast layers and segments of the American population. At that moment, we no longer recognize ourselves.

Prairie Fire

National political campaigns are inherently toxic. We do elevate the image of Lincoln and Douglas speaking to thousands of white Illinois farmers and merchants, ex tempore, for hours at a time, debating legal and philosophical intricacies of sovereignty and citizenship. That is our template for civic engagement and political discourse. But in that time, as in our own, hidden below the patriotic bunting, the wooden decks of the speakers platforms, the muddied fields, muffled by the raucous cheers and jovial banter of these tent meeting huskings, beneath those honest images of rough democracy, the prairie fires burn hot through the soil. Truly, the Lincoln-Douglas debates were the exception that proves the rule regarding the savage intent and bitter leavings of the political contest. Politics is a bare-knuckled brawl.

On April 15, 2010, as (formerly) New Left and (now) Old Right historian Ronald Radosh reported in The Daily Beast, Steve Bannon delivered a rambunctious speech to a Tea Party rally in New York. On Tax Day (in the year the Republicans swept aside the Obama majority in the House, threatened its majority in the Senate, and rolled through the state legislatures like so many haystack twisters) Bannon unleashed a torrent of disdain for financial architects and political enablers of the Great Recession that had spun 15 percent of the nation into poverty and unraveled the lives of countless other millions caught on the pitchfork of mortgage arbitrage.

While Occupy Wall Street would one year later voice similar contempt and outrage for the One Percent, Bannon’s assault on liberal elites assumed existential dimensions – the Goldman Sachs vampire squid as a cosmopolitan, many-tentacled agent of globalization that had sucked away, not simply the wealth of the middle class, but its sovereignty over the American Dream. The Tea Party, heirs to pre-revolutionary Boston Harbor anti-tax incendiaries, were those stolid, virtuous Americans – Bannon would call them his “hobbits” – who make the country work, “the beating heart of the greatest nation on earth.”

The politics and messaging here are slippery, but to properly position them Radosh isolated Bannon’s concluding remarks: “It doesn’t take a weatherman to see which way the wind blows, and the winds blow off the high plains of this country, through the prairie and lights a fire that will burn all the way to Washington in November.” As Radosh reminded us in his article, Bannon (a committed Deadhead and Springsteen fan back in the day) was paraphrasing from Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues, simultaneously invoking the revolutionary, system-shattering instincts of the Weather Underground, late-1960s insurgent and militant and violent spinoff of Students for a Democratic Society.

Weather Underground members – Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn, specifically – in 1974 published a book titled Prairie Fire that presented themselves as a guerrilla organization (“communist men and women underground in the United States”) committed to destroying American capitalism and the liberal state. Bannon’s language indicates the extent to which he associated the Tea Party with a similarly revolutionary, elite-stomping, state-smashing mission on behalf of America’s forgotten heartland hobbits.

Deep State

Steve Bannon’s radical instincts and Ayers allusions poignantly illustrate the disintegration of language as the common currency of our civic identity. Because of course, (the very non-radical and measured) Barack Obama’s very casual Chicago connection to Bill Ayers in the context of education policy discussions (Ayers became a beloved education professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Education) had already become staples of right-wing flame-throwing (see this sampling from Breitbart), a turd-like reality which (the far more radical and subversive) Steve Bannon was obviously poking with his Prairie Fire reference.

Beyond the Daily Beast article, Bannon’s winking, subversive Ayers references obtained no obvious traction with anyone on the right (or elsewhere, for that matter), an indication of the extent to which emotions have overwhelmed language and basically destroyed the capacity of words to in any meaningful way frame any public and shared concept of reality.

We have many ways to think about the impact of this bizarre surge of emotion into the public sphere (see a great historical instance of this phenomenon in Lessons From the Fake News Pandemic of 1942). But in our current historical moment, its significance has been revelatory. Brooding, profane Irish Steve Bannon is radical because he does not believe in the Enlightenment project. His ideas and instincts are pre-Enlightenment, and so quite alien to the lenses we are accustomed to using for our imaginings about the American experience.

I’m going to dive more deeply into Bannon’s intellectual influences. For now, suffice to say that these influences do not include Locke, Madison, Jefferson, or Lincoln. Politically speaking, Bannon is a traditional Catholic conservative (of the Mel Gibson variety) who is profoundly in tune with the darker demons of the human soul, a media Svengali skilled at orchestrating chaos and mayhem.

Our current titillation with the Deep State, working its dark arts from within US intelligence agencies, sheds light on Bannon’s quite remarkable political achievement, which has been (via Trump, Breitbart, and his documentaries) to rip away the rather bland and mechanical surface of American politics and expose its exotic underbelly, a quasi-medieval jurisprudential apparatus funded and supported by a varied group of wealthy and powerful free-market and socially conservative individuals and institutions, ranging from Charles Koch to Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke, but also encompassing canonically minded American judges, including Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas (and, formerly, Antonin Scalia).

This version of the Deep State is not primarily a Protestant evangelical movement, which remains far more in the American grain than these elements in tune with Steve Bannon, for whom the currency of the land is not grace or justification, but power, the terrestrial control of both bodies and minds. To fully understand the intellectual foundations of this legal apparatus, we need to leave the Enlightenment and return to the world-historical vision of the medieval Christian church in its encounter with Islam.