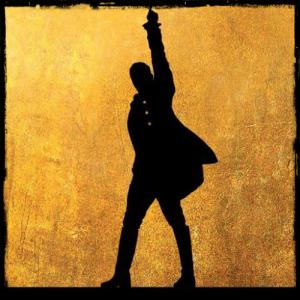

I’ll just say it. Four years out, Hamilton the Musical remains the most important American cultural moment of the 21st century. The genius of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s creation is that his imaginative, hip hop, racial caste/casting adaptation of the massive Ron Chernow biography of Alexander Hamilton almost instantly, and effortlessly, has changed the way we think about American history.

Part One / Alexander Hamilton, Superstar

Music and the Historical Imagination

Any human community dies, quickly, when it can no longer, inclusively, sing about itself, laugh about itself, and know and claim its origins in terms that can refresh and surprise its youngest generations. In the past few decades, founding father and presidential biography has become a lucrative, and quite annoying, cottage industry. Annoying because, with the exception of philosophically minded thinkers such as the incomparable Garry Wills, the majority of these biographers have employed conservative story-telling methods that have presumed a quite frozen continuity in our history as a nation that frankly no longer speaks to anyone in the digital age who is not white and older than 40. More on this shortly, but the point is essential for understanding Miranda’s genius, which incorporates a popular culture sensibility that fully eludes older and more ponderous biographers such as David McCullough, with their preponderance of affluent, older, white male readers.

Chernow’s Hamilton biography is fantastic – lucid, human, persuasive. And more on this shortly, as well. But Hamilton the biography, first published in 2005, is significant beyond its own terms because it provided Lin-Manuel Miranda with the raw material for his antic, inspired reimagination of the founding of the American nation.

Hamilton echoes Jesus Christ Superstar in its use of musical storytelling and a contemporary cultural lens to radically rearrange how we imagine the world. Jesus Christ Superstar, which composer Andrew Lloyd Weber (at the age of 23) and lyricist Tim Rice debuted on Broadway in 1971 actively (and quite subversively) interpreted the gospels through the lens of the rock counterculture and Aquarian sensibilities of that era. As with Hamilton, the energy in Jesus Christ Superstar, its powerful capacity to connect with its audience, was enormously enhanced through storytelling and musical reliance upon contemporary attitudes, sensibilities, and linguistic stylings, along with ironic allusions to modern life contained within depictions of storied political events.

In JCS, rock music energizes and refreshes our understanding of Jesus and Judas – the musical medium both enabling and requiring the radical reshaping of the frozen, canonical, and mostly reactionary perspective on the life and meaning of Jesus. Similarly, hip hop as a creative medium propels Hamilton in directions that literally mandate a kind of super-heated melting of history that can’t help but forever disrupt and recast how we relate and connect to our nation’s birth.

History’s Orphan

Lin-Manuel Miranda places Hamilton’s orphan status at the center of the story in his musical. One of the ironies of American historiography is the extent to which historians and the nation’s historical imagination have also, until fairly recently, orphaned Hamilton. Hamilton’s uncertain status in our national storybooks almost certainly is the result of his death at the age of 47 (or 49) in 1804, never having been able to add POTUS to his resume of accomplishments and achievements. But this uncertain status is also almost certainly related to his complex origins and identity – which place him both in the West Indies and in New York City, but which by the same emotional logic have denied him a fully national identity. This is also, of course, an important theme for Miranda’s Hamilton musical. Additionally, Hamilton’s association with abstruse matters of high finance and with wealthy banking elites has routinely located him on the dark side of political forces in the American morality play, which has consistently favored the simple agrarian virtues and decentralized democratic values associated with New England town meetings, Antifederalism, the Bill of Rights, and Jeffersonian-Jacksonian populism. Hamilton. Slippery, scaly sea creature creeping to shore under cover of darkness. Hamilton. Necropolitical agent of dispossession and despair.

And so, Hamilton really never had a chance. At least not until the last third of the 20thcentury, when Forrest McDonald, brilliant and bilious southern conservative historian (who died in 2016 at the age of 89) reclaimed him for the entire nation, largely by accepting the common tropes more conventionally used to deny Hamilton purchase in the national pantheon. McDonald simply flipped these tropes – formerly dark marks of anti-democratic perfidy and counterrevolution – into emblems of honor and heroism. His Hamilton shaped the Constitution, saved the Union, and established it upon the soundest of political and financial foundations, even as these actions consistently cut against the prevailing popular and democratic passions of the day.

Ironies of Historical Reclamation

Forrest McDonald was a (self-proclaimed) “unreconstructed” admirer of Hamilton and Federalism who grew up and received his degrees in Texas and taught American history for more than 40 years, for most of that time at the University of Alabama (from where he would, at his nearby home, quite charmingly write using a yellow legal pad and without wearing any clothes). McDonald’s unvarnished passion for Hamilton encompassed the full breadth of virtues one might associate with classical founder-heroes: native genius, intellectual strength, literary profluence, personal magnetism, military derring-do, political savvy, and administrative and financial legerdemain.

For McDonald, however, Hamilton’s primary virtue – the one that to some degree enabled all of the others – was his “detestation of dependency and servility.” Which when one thinks about it, is really a remarkable statement, because the negative turn of phrase (emphasizing not Hamilton’s own undeniable independence, self-reliance, and mastery, but merely his detestation for the absence of those qualities in others) mostly served to draw attention to McDonald’s own dripping and enduring contempt for the United States government and the American people, both of which in his historian’s mind disclosed an unremitting and pitiless descent from the glory days of the nation’s founding.

McDonald did reclaim Hamilton for the nation then, yes, but imperfectly, for he did so on terms that only served to also distance the man and his greatness from the nation, testament not to the nobility of the nation he founded, and of its citizens, but to their decadence and decrepitude in comparison to the grandeur of the world of their fathers. To put it bluntly,” McDonald said when he delivered the National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Lecture in 1987 on the bicentennial of the US Constitutional Convention, “it would be impossible in America today to assemble a group of people with anything near the combined experience, learning and wisdom that the 55 authors of the Constitution took with them to Philadelphia in the summer of 1787.”

McDonald always remained an outlier politically by virtue of his Deep South eccentricities He participated with secessionist and generally irascible historian Grady McWhiney in propounding the “Celtic Thesis” of Southern cultural identity. He also raised hackles when in response to challenges (from Thurgood Marshall, among others) to the perfectionist view of the Constitution, because it sheltered slavery, he said “the condition of the French peasants was far worse than that of the American slaves, and that was heaven compared to the Russian serf.”

Hamilton and Conservative America

Regional eccentricities aside, McDonald’s scorn and vitriol for the American nation post-founding was fully consonant with the Reagan-era appropriation (championed by Edwin Meese and Antonin Scalia) of Alexander Hamilton as the standard-bearer for the Federalist Society and the entire legal conservative movement, where he became the avatar of neoconservative justifications for a “vigorous” executive, particularly in matters of national security and foreign policy (and, far less persuasively, for a libertarian vision of decentralized authority).

More poignantly, McDonald, legal conservatives, and academic political philosophers of the Straussian bent hand-delivered Hamilton to the American people, but with the stipulation that his historical meaning for the nation was largely aspersive. Not the best formula for bringing history to life for 21st century Americans. It would take Brooklyn native and financial journalist and biographer Ron Chernow to make Hamilton specifically relevant and meaningful for contemporary Americans.

Part Two / Hip Hop Historiography

Probably the most significant achievement of Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton biography, likely something no previous generation of historians and biographers could have achieved (certainly not Forrest McDonald) was the unpacking of the interior worlds inhabited by Hamilton and others who moved within his orbit.

Peripheries of the American Mind

In The Dream of the Great American Novel, Lawrence Buell emphasizes the post-World War II liberation of the individual protagonist from realist perspectives characterizing novels of the first half of the 20th century, a kind of emancipation from history that carries over into the biographical style and methods used by Chernow in his biographies of Morgan, Rockefeller, Hamilton, and Washington. Chernow, with his post-World War II, Brooklyn, Jewish, Yale, and Cambridge (England) origins, is by no means a man of the periphery. But by fully releasing Hamilton as a creature/creation of New York City, he reimagined New York, of all places, in almost magically realistic terms, as a periphery at the center of the new American nation. It is this approach to Alexander Hamilton that captivated Lin-Manuel Miranda and that created the hip hop history opening for Hamilton the Musical.

Revolutions require peripheries of both mind and space, of interior and exterior. While we have conventionally thought about the American Revolution as a colonial revolution, in reality the political establishment in the colonies was closely tied to and dependent upon British finance, British culture and customs, British laws, British patronage, and British indulgence and forbearance. What Miranda opens our eyes to is the possibility that the old, sodden story of the national founding inscribed in our monuments and in our court cases and in our text books may altogether miss the animating spirit of the American Revolution (and perhaps by definition of all revolutions), which was that marginal peripherals were the ones who (bringing to its challenges no stake in the status quo and a fresh, unencumbered sensibility) fully understood its promise and who fully fanned its flames. That Miranda would locate this peripheral sensibility in New York City, in what we might now call, in the 21stcentury, the Empire State of Mind, is one of the most terrific ironies to emerge from the Hamilton musical.

Empire State of Mind

Here are some ways to capture the meaning of Miranda’s musical reimagination of Alexander Hamilton. First, let’s consider New York as the revolutionary epicenter and what that means from the perspective of the city’s residents nearly 250 years after the Revolution. Let’s also consider the themes emerging from Hamilton’s story line and musical lyrics: New York City, orphan, immigrant, bastard, slavery, West Indies.These are personal origins themes. Which also matter enormously for meanings we assign to our national origins.

In most canonical narratives of the Revolution and of the nation-building period that follows (certainly in those that inform the collective mythic imagination), New York City is missing in action. While even in 1776 arguably the pivot of the colonies commercially and financially and ethnically, New York slips between historiography’s binaries and eludes capture, with the result that the emerging national identity is largely viewed from the perspective of New England merchant and Southern planter interests.

History is happening … in the greatest city in the world. (I.5)

Following Chernow’s lead, Miranda places New York City at the center of the drama and requires the remaining colonies/states to dance around the pole it sets in the ground. The American colonies had not yet achieved any significant population density and most of its citizens lived on farms. Only the small minority of citizens packed into a handful of cities really possessed the means and the vision to step into history as active participants. In New York City, in particular, the immigrant drift represented tinder waiting for its match.

In New York, you can be a new man. (I.1)

In Miranda’s skilled hands, reading a hip hop sensibility backwards from the 21stcentury to the 18th century, Hamilton captures and contains within himself the original Empire State of Mind. Orphan, bastard, West Indies immigrant, with a limitless capacity for reinvention, Hamilton’s identity and fate, and that of the nation, are intertwined.

Another immigrant comin’ up from the bottom. (I.1)

And this is the point. Hamilton’s illegitimate, marginal status does not have to be, and is not always, a liability. What does this marginal status give Hamilton? Peripheral vision. He brings an outsider’s perspective, an immigrant’s perspective, to the center of the revolutionary struggle.

Immigrants: We get the job done. (I.20)

Clearly this is Miranda’s interpretation, and who can doubt the inspiration pride and interest in his own Caribbean origins and his awareness of the bubbling-up impact of immigrant cultures in New York City, and elsewhere in the nation? But once Miranda introduces these themes, the audience itself experiences a riveting moment of self-recognition Because of course the orphan/bastard/immigrant narrative also makes sense for understanding the nation’s origins! And once we accept that premise, it is difficult not to see New York City, which even as the Revolution broke, already was the immigrant center of the new world, as the pulsing, rhythmic heartbeat of the Revolution.

Band of Brothers

What does this marginal sensibility produce? In the Hamilton musical, friendship, the band of brothers, drives the insurgency. Commitments of love and loyalty unavailable to conscripted or mercenary British troops makes possible the informal, shifting, liquid style of warfare used by the revolutionary insurgents – the inception of guerrilla warfare as we now know it, in which the British Army can never hope to outrun, outmaneuver, or outlast American fighters.

Hamilton’s posse (Marquis de Lafayette, John Laurens, and Hercules Mulligan) serve subversive, comic goals. They are the lovable scoundrels who capture the antic, democratic spirit of the new nation. In real life, of course, Lafayette and Laurens were wealthy, well-born, well-educated soldier-statesmen. Hercules Mulligan, graduate of King College and a tailor, was an important spy for the Revolutionary cause. But even in their comic musical personas, all three remain true to their historical roles and cement in our minds new ways of thinking about important elements of the revolutionary narrative.

Hercules Mulligan, I need no introduction,when you knock me down I get the fuck back up again! (I.20)

Hercules Mulligan offers Miranda the opportunity to introduce themes of womanizing and sexual license into the narrative that foreshadow later scenes of sordid sexual politics (the Maria Reynolds affair) that complicate Hamilton’s founder-hero status, but that also more fully humanize him and make him emotionally and psychologically accessible to Americans in the 21st century.

Je m’appelle Lafayette, the Lancelot of the Revolutionary set! (I.2)

Lafayette condenses the complexity of the French-American relationship, along with the divergent meaning of the two nation’s revolutionary moments. Lafayette’s character also brings an insouciant spirit of play to the founding narrative, introducing a lightness of being that the more earnest Hamilton, occasionally, can share, but that also strengthens a claim about the Revolution and the founding that 21st century Americans can appreciate, which is the subversive energy of irreverent humor that won’t concede any special status to convention or authority.

But we’ll never be truly free, until those in bondage have the same rights as you and me. (I.3)

John Laurens’ duel with Charles Lee choreographs the intricate dueling/honor rituals that are so pivotal in the second act of the musical. Laurens’ bold soldier-slave emancipation scheme of course also lets Miranda spotlight the ironic foundations of freedom in a slaveholding society, as well as dissimulations required to whitewash or elide fractures in the Constitutional foundations produced by the failure to confront slavery.

The posse also undermines familiar historiographical biases emphasizing that the insurgency was largely a rebellion against abuses of parliamentary and (ultimately) royal authority (but in no way a social revolution) and that freedom was simply about redressing these abuses, and so in reality a restoration to political practice of principles already contained within the traditional constitutions and charters of government.

Freedom and Inclusion

Problems with this historical perspective on the meaning of freedom in the American Revolution unfurl, especially as the 18th century begins to seem to us like a very long time ago. Reducing the meaning of freedom to political restoration is thin gruel indeed for a hungry nation. a “scarcity” view of freedom as a precious commodity that entirely undermines itself by justifying a narrow and exclusive apportionment. Freedom as political restoration must ultimately be about preserving existing status, privilege, and opportunity, not fully extending it on the basis of natural rights commitments to the equality of all humans the founders themselves emphasized.

Miranda cleverly imagines Hamilton’s posse as revolutionary agents of inclusion, not of exclusion, which allows him to shift the focus of the Revolution to its aspirational and implicit goals, alongside its practical aims. And so, King George III and his minions (including fat Charles Seabury!) do shape the narrative, but only to a limited and non-exclusive degree, which creates room for the relationship between actual slavery and actual freedom to assume a far more commanding role in the conflicts that push forward the story.

Finally, Miranda brilliantly disarms the politics of a focus on slavery and race, which are simply hot buttons that in less sensitive hands would sink the musical before it left the harbor. How does he do this? By selecting African-American and Hispanic-American actors to cast virtually every role in the drama! By casting in a manner that shifts attention away from the race of founders, the experience of watching the musical itself allows us almost without effort to imagine the meaning of the national founding in more universally inclusive human terms!

Part Three / A Mind at Work

When I was seventeen a hurricane / destroyed my town. / I didn’t drown. / I couldn’t seem to die. / I wrote my way out, / wrote everything down as far I could see. / I wrote my way out of hell. / I wrote my way to revolution. / I was louder than the crack in the bell. / I wrote Eliza love letters until she fell. / I wrote about The Constitution and defended it well. / And in the face of ignorance and resistance, / I wrote financial systems into existence. / And when my prayers to God were met with indifference, / I picked up a pen, I wrote my own deliverance. (II.13)

Animating History

One of the great feats of derring-do achieved by Lin-Manuel Miranda in Hamilton the Musical is to make Alexander Hamilton’s frenzied literary mind accessible and exciting – this fanatically popular musical is deeply about words! And about writing as creation. For those among us (probably most among us) who find what was written in the late 18th century, by the nation’s greatest political and constitutional minds, to be like post-holing across a glacier (just really not worth it, not matter how beautiful the view from the other side), this is no trivial achievement!

Miranda’s Hamilton uses contemporary discourse to connect his audience emotionally to a profound moment in America history. Hamilton, Burr, Jefferson, Washington, Angelica, and Eliza – all speak and sing to us across a range of modern dialects, colloquialisms, and referents, none of which would obviously have any meaning for anyone living in the 18th century. Miranda puts the burden on history to bend toward us, rather than require us to bend toward history!

Obviously, use of anachronistic language risks distorting or misrepresenting the historical record. But because Miranda layers his story on top of Ron Chernow’s impeccably researched Hamilton biography, the effect is to animate the story as we know it to be, rather than create an animation that bears no resemblance to the historical reality. Hamilton is no Disney production. This is an exciting way to bring history to life!

Let’s explore some of Miranda’s animation methods.

Hip Hop Stylings

Cuz I will pop chick a pop these cops till I’m free! (I.2)

Miranda’s point of departure for the musical’s historical sensibility is contemporary hip hop, an urban, largely Afro-American medium entirely dependent on word-play and rhythmic stylings.

I’m John Laurens in the place to be! / Two pints o’ Sam Adams, but I’m workin’ on three, uh! / Those redcoats don’t want it with me! / Cuz I will pop chick a pop these cops till I’m free! (I.2)

In Hamilton, hip hop delivers the musical energy that transports us back to the late 18th century, giving the drama its unique personality, and it is largely that energy which allows/requires us to perceive words as the basis of personal action and of historical agency, with the self-assertion and ego-centrism familiar to hip hop aficionados closely associated in Hamilton the Musical with our national founding acts.

I am the A-l-e-x-a-n-d / e-r-we are-meant to be… / a colony that runs independently. (I.2)

Perhaps less obvious, but potentially far more salient for establishing the metahistorical significance of Hamilton the Musical, is the inclusive generosity of hip hop as a sampling medium. In Hamilton, Miranda himself borrows freely from (and acknowledges) music authored by Rodgers and Hammerstein and by Gilbert and Sullivan, along with songs written and produced by a variety of hip hop artists, most notably Notorious B.I.G.’s Ten Crack Commandments.

Hip hop is protean, lacking a musical center and therefore requiring no formal margins or boundaries (in the musical, Burr assigns the protean label to Hamilton). The interactions between musical styles and genres is particular, specific, and partial, but for those reasons also flexible, surprising, and innovative – a guerrilla form of contemporary music that aligns quite nicely with the nimble, shape-shifting, complex, but largely non-authoritarian and non-centralized inceptions of the American Revolution. From this lens, the traditional top-down and exclusive view of the Revolution as the historical property of white male elites slips away almost without our noticing. The Revolution, suddenly, something that belongs to all of us.

Rise Up

Why do you write like you’re running out of time? (I.23)

Miranda makes Alexander Hamilton’s active mind the centerpiece of the personal story – the biography standing in for the national history. Alexander Hamilton’s prodigious literary output reflected his political passion, yes, but also served as vehicle for fulfilling his personal sense of destiny, his manic drive to rise up. And while one lesson here is really that most improbable, transformative acts of creation require from their principal creators this sense of destiny, and urgency, the more salient and specific insight Miranda communicates to his audience concerns Alexander Hamilton, himself, contesting the vanishingly small amount of time available to him to accomplish everything that needed to be accomplished, leading to a pure fusion of thought and action. Words don’t simply represent the sampled, edited, selective output of Alexander Hamilton’s mind – his words are his mind, ushering forth in real time with cascading, transformative impact unique even among the stellar minds of rival founders of the American republic.

I’m lookin’ for a mind at work. (I.5)

The emotional impact of Hamilton the Musical largely emerges from an audience awareness that perhaps it is actually words that propel forward revolutions, not warfare. In the musical, the revolution unfolding in New York City is mostly a revolution of ideas and principles seeking almost literally to birth themselves. The fabulous Schuyler sisters, slumming downtown in 1776, sensing that history is happening in Manhattan, and looking for a mind at work, are searchin for an urchinwho can give them ideals. And so it matters enormously, for how we perceive Hamilton, but even more for how we perceive politics and revolutions, that his sex appeal for the Schuyler sisters, who are captivated by his intelligent eyes, is presented to us largely as a matter of his inner brilliance (and not his hunger-pang frame) (I.11)

From the start, then, the musical storyline makes clear that Alexander Hamilton – who reads every treatise on the shelf – conforms fully to the zeitgeist of the American political and cultural revolution/revelation, and in some ways represent its apotheosis. Hamilton himself sings, between all the bleedin’ ‘n fightin’ I’ve been readin’ n writin’. (I.3) Clearly Hamilton’s own youthful aspirations to achieve immortality through battlefield martyrdom (that destiny instead falling upon his close friend John Laurens) often overrode his commitment to reading and writing. However, his active mind, and post-Revolution turn toward politics, ultimately required Hamilton to almost exclusively read and write.

Single Combat

You must be out of your Goddamn mind! (II.7)

We all know the fate awaiting Alexander Hamilton. In Miranda’s musical interpretation of his life, prefigurations of personal and political violence (specifically duels involving John Laurens and his son Philip) foreshadow Hamilton’s own demise. But these prefigurations also spotlight the honor/shame mandate rooting itself in the national mind (ironically) during this era of Enlightenment. This cultural and psychological mandate required men to defend their honor (or the honor of those near to them) at any hint of disrespect from others.

As his borrowing from Ten Crack Commandments indicates, Miranda is surely aware of the power these scenes of single-combat will exercise over those in our own century who witness cycles of violence and retaliation in minority communities, psychologically a perilous and primitive condition in which young men (or boys) sacrifice their bodies to safeguard at all costs fragile structures of the self. And while the circumstances are obviously not fully analogous – duels themselves were highly scripted and choreographed, with many opportunities to slide away from a terminal event, the connections are sufficiently real to claim the attention of contemporary audiences.

And so, let’s accept this backdrop of threat and danger triggered by the need to respond to any challenge, real or not, significant or not, with a call to arms. One of the great juxtapositions of the musical occur when Miranda creates battle rap scenes which offer up an alternative, language-driven framework for disputation as a form of mass entertainment, encouraging disrespect and the art of the insult, with diminished threat of repercussions or retaliation.

A civics lesson from a slaver. Hey neighbor, / Your debts are paid cuz you don’t pay for labor. (II.2)

In Hamilton, Cabinet Battles between Jefferson and Hamilton, both of which emphasize the difficulties of governing (the first focused on the national debt and the second considering whether to aid France in its war with Britain), sketch an alternative foundation for managing conflict and disagreement to violence, with its ultimate claims upon the body.

We signed a treaty with a King whose head is now in a basket. / Would you like to take it out and ask it? / “Should we honor our treaty, King Louis’ head?” / “Uh… do whatever you want, I’m super dead.” (II.7)

The Cabinet Battles accurately communicate the intense dislike Hamilton and Jefferson felt for each other – they were never friends and associates like Hamilton and Burr. In the end, however, Hamilton and Jefferson somehow understood each other, and could accommodate each other and leave room for each other, while Burr and Hamilton, operating outside of this framework and exposed fully to the honor / shame imperatives of the underlying culture, could not.

Writing History

Who lives, who dies, who tells your story? (I.19)

Hamilton the Musical isolates and elevates the emotional need to author one’s life story. Hamilton himself – who writes like tomorrow won’t arrive, like he needs it to survive, ev’ry second he’s alive (I.23) – personally illustrates powerful connections between words (as the substance of authored stories about oneself and one’s nation) and public authority, which ultimately derives not just from the monopoly of force, but more profoundly from control of the narratives by which we live and through which we understand ourselves.

In this sense, Hamilton drives home the personal meaning of history, generally, which is that it is ultimately something you write, not make (or perhaps something you can make only by writing). If your achievements are not remembered, if they do not influence the thinking and the actions of others in the future, can one say they are real? Did they ever happen? Did you exist?

These are questions that plagued Hamilton, and that typically afflict generations for whom eschatological religion and the condition and status of a personal soul matter little. Death is the specter one tries (while aware success can only be fleeting) to outrun.

I imagine death so much it feels more like a memory / when’s it gonna get me? / in my sleep? Seven feet ahead of me? / comin’, do I turn or do I let it be? / See, I never thought I’d live past twenty. / Where I come from some get half as many. / Ask anybody why we livin’ fast and we laugh, reach for a flask, / we have to make this moment last, that’s plenty. (I.3)

The fatalism of these words will resonate for minority, urban youth (and probably for all 21st-century youth), whose own experiences growing up are largely the lens Miranda uses for imagining and connecting to American history, with hip hop itself specifically a medium for translating one’s personal history in defiant narrative terms that explicitly make the case for one’s own existence.

Rapping into darkness achieves nothing – connecting with others is the only way to cement one’s own immortality – to matter, to prove one existed. Nation-building itself is ultimately the most transcendent form of immortality, however – establishing precepts, laws, and institutions that endure independently of any clay-footed human. Hamilton soars beyond the local and egocentric awareness of conventional hip hop to assert that the most enduring form of personal story-writing occurs only when in the act of writing one’s own story, one also, and principally, is writing the nation’s story. The nation imbued with self, not standing apart from self.