Below are excerpts from a paper I published in 2009 in the journal Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture. The paper was the initial exploration of the theme which guides this blog, as well as a forthcoming book I am drafting on the educational mission of Catholic universities.

The title of the paper is “The Boutique and the Gallery: An Apologia for a Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Academy.” The thesis is that the boutique and the art gallery represent two divergent approaches to education, and that Catholic universities are universities in the truest sense (aiming for integration of knowledge), whereas other types of higher education have abandoned the quest of integration and descended into consumer-driven multiversities.

A university (Latin “turning towards the one”) is a place where students and researchers strive for wisdom. A multiversity (“turning towards many things”) is where consumers collect artifacts to sell on the market.

The first issue is one that preoccupied the earliest thinkers in the West: namely, the question about knowledge itself—what it is, what it strives for, what it can be used for. The second issue has to do with what we want to hand on—the Latins used the verb tradere and its cognate nouns: traditio (a handing on), tradita/ traditus/ traditum (the feminine/masculine/ neuter “something handed on”). Assuming we know what we’re doing when we use our knowledge, what then ought we to hand on to our students? What things ought we to hand on, and what practices ought we to teach them in order that they might continue the work we ourselves have inherited?

There are two main models abroad in higher education today. The first model is that of a collection of boutiques.

In a typical boutique, say, “English romanticism,” a procurement associate (let us call her a “faculty member”) is responsible for working with various vendors—Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats are a few of the more prominent brands—to develop new product lines. Here she develops a new psychoanalytic look at Coleridge; there she offers a postcolonial critique of Frankenstein’s monster. Her work is an exercise of both skill and creativity; not only must she have thorough knowledge of each of the vendor’s products, but she must also have the ability to develop new ideas, new perspectives, and new insights into how these products might be marketed, adapted for use in new ways, and applied to the needs of the contemporary consumer.

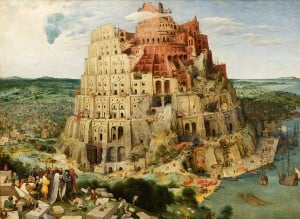

The second model is that of the gallery of art.

Here are works from ancient Greece and Rome; there are ancient near Eastern pieces. In one room we find early medieval art, and in another works from the height of the Italian Renaissance or early modern Latin America or late modern Africa. The media are varied: sculpture and bas-relief, oil and tempera, daguerreotype and digital photography. The subjects range wildly from the heroes and gods of the ancient world, to the piety of the medieval period to the explorations of modernity and beyond. The sacred and the secular coexist: robust and colorful explorations of sexuality in the same rooms as contemplative chiaroscuro drawings of the symbols of faith. (…)

The gallery is both a repository for the old and a training ground for the new. Those who work at the gallery are committed to understanding how earlier artists chose their subjects, selected among different available media, drew from others’ work. This commitment informs their own original work, which they hope one day will be deemed worthy of inclusion in this august collection. Some see themselves primarily committed to their work with the learners while others find themselves drawn more to the exchange of ideas to inform their own art.

Each model has its own reason for existing in the first place, as well as its own meaning, depending on what it is aiming at (telos).

In the boutique, the telos is the running of the market and the benefit that the market delivers to the individuals who participate in it. And to be sure, the market does benefit many people; it provides livelihood to individuals and communities and thereby serves the common good. Yet the limitation of the boutique—and therefore of the market that the boutiques serve—is that the benefits provided are in the form of instrumental goods rather than goods in themselves. The boutiques cannot aspire to serve the greater goods of the human family: those goods which involve right relationships between people, and which generate hope and involve the solidarity of love and suffering. The gallery, on the other hand, seeks the telos of beauty, and as such serves both as a good in itself and a good that generates still other goods.

The Catholic intellectual tradition (CIT) is necessary within the context of the academy precisely because it embraces a freedom not available to institutions governed by market forces (which include the tides of democratic government).

At root the issue remains epistemological and, ultimately, pedagogical: what shall we teach? From the CIT comes a compelling answer: above all, we must teach a language which enables people to constantly raise the most compelling questions that face human beings. For only with an ability to talk about such fundamental questions—about the meaning of death and suffering, of joy and hope, of God and God’s potential revelation to humankind—does any intellectual exercise contribute to a vision of the good. Of course Catholic tradition has developed a superstructure of doctrines, philosophies, theologies, laws, and so on. We can envision this superstructure as a kind of forum within which people address ultimate questions. Many colleges and universities won’t even touch these kinds of questions—they are too controversial—but those shaped by the CIT will engage them with relish, inviting both those whose faith commitments are shaped by the superstructure and those for whom the superstructure is irrelevant. Because the CIT is not coextensive with the Church, it has the flexibility to engage all people on their own terms.

Next week, I will highlight the most recent issue of Integritas, in which members of the Boston College Roundtable discuss the ways their work contributes to this Catholic intellectual tradition, specifically in reference to the theme of “science and the person.” The beauty of this project is precisely the fact that the canons of good university work– doing research, sharing work honestly, making discoveries, and teaching students– are inclusive of all people of good will. Rather than being subservient to market forces, scholars in a Catholic context enjoy a robust academic freedom.