If we think of the poisonous serpents as humans in rivalry leading to violence and the disintegration of culture, Moses asks them to change their focus by looking at the bronze serpent instead of each other.

-Rev. Tom Truby

Pastors have a frequent question when they begin to discover mimetic theory. “That’s great. But how does it preach?”

Reverend Tom Truby shows that mimetic theory is a powerful tool that enables pastors to preach the Gospel in a way that is meaningful and refreshing to the modern world. Each week, Teaching Nonviolent Atonement will highlight his sermons as examples of preaching the Gospel through mimetic theory.

Lent 4 – 2018

March 11th, 2018

Thomas L. Truby

It Is Hard to Look at the Poisonous Serpent Particularly When He Is Us

In 2012, on the fourth Sunday of Lent, I wrote a sermon entitled “Deliverance!” It told the story of the Hebrew people traveling toward the Promised Land and running into an infestation of poisonous serpents. The context for this had the people losing faith in Moses and his God. Their strident voices became urgent as they asked, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we detest this miserable food.”

Yes, you heard correctly. They did say there was no food in the first part of the sentence and they detested the food in the second. Apparently there is food, they just don’t like it. So they actually have everything they need. Their complaint even admits that, but they are still not content. They are in the midst of a falling-out amongst themselves, with their leadership and with God.

Then, according to the story, “the Lord sent poisonous serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many Israelites died.” Do you really think God sent poisonous serpents among them or could the poisonous snakes be stand-ins for rumors, back-biting, slanderous conversation and deliberate falsehoods driven by self-interest?

Could the poisonous snakes represent a deepening violence that is infiltrating the community, seeping in everywhere, and destroying the quality of their life together? If this is true, then people were biting and infecting each other with a kind of human poison we know all-to-well. We see this kind of poisoning happening all the time in our own culture and it seems particularly bad right now. Most of us worry about it and wonder where it’s all going to lead.

Sensing the disintegration, some leaders came to Moses in distress and with a confession. They say, “We have sinned by speaking against the Lord and against you; pray to the Lord to take away the serpents from us.”

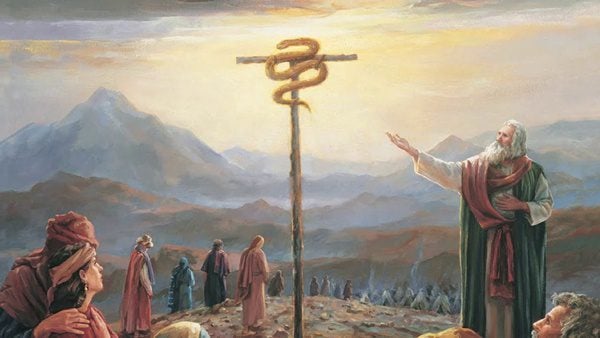

So we move to the next chapter in this strange story. Moses prayed to God and the Lord said to Moses, “Make a poisonous serpent, and set it on a pole; and everyone who is bitten shall look at it and live.” If we think of the poisonous serpents as humans in rivalry leading to violence and the disintegration of culture, Moses asks them to change their focus by looking at the bronze serpent instead of each other. In other words, their focus on the bronze serpent will break the hypnotic trance they are in and force them to examine themselves. They have become each other’s poison and must realize this before they can escape the lethal serpents. The change of focus will stop the escalating rivalry that pulls them toward violence and they will be saved from destruction as a community.

Now we switch to the Gospel on this fourth Sunday of Lent. Two verses before John 3:16, John writes, “And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have ‘a share in the life of God’s new age.’” NT. Wright says that “a share in the life of God’s new age” is a better translation of the original Greek then “eternal life,” the phrase the New Revised Standard Version uses. It would take some work on my part and a whole sermon to explain this, but it makes sense to me. When John talks about the Son of Man being lifted up, he is talking about Jesus’ crucifixion where Jesus was lifted up on the cross like the serpent was lifted up on a pole.

And the parallel between the serpent lifted up and Jesus being lifted up operates on a second level. The book of Numbers is clear that the serpent was a poisonous serpent. It wasn’t a garter snake. It was a rattler. How is Jesus, being lifted up on a cross like a poisonous snake hanging on a pole? Because he shows us our own poison, something we don’t want to look at or see but must if we are to find salvation from our own poison. We have to see that we are the snakes, forgiven and in the process of being changed and this process is participation in God’s new age, his coming and now here for those who look to the cross to see human anthropology on display.

Moses, at God’s directive, told the people to look at the image of a poisonous serpent if they wanted to be saved. In other words, they had to look at what they did not want to see in themselves. They, in their hearts and in their relationships, were the serpents that bite and kill each other. Or as Paul writes in Ephesians, “We were by nature children of wrath, like everyone else.”

We are now ready to for John 3:16. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but share in the life of God’s new age.” (N. T. Wright again) God gave us Jesus on the cross so that we could see what we do when left to our own devices. It is in turning to look upon the forgiving Son of Man lifted up on a cross that we are rescued from our rivalrous and violent ways—not just we as individuals (This is the error religious conservatives make) but as whole communities and cultures, in fact, the entire world. The shift in focus from violence to nonviolence and from accusing to forgiving heals the world. In doing these things we share in the life of God’s new age that Jesus has inaugurated.

Moving on, John 3:17 says “Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.” Jesus didn’t go to the cross to expose and condemn us. He went to the cross to provide us a way out, to save us. And he saves us by forgiving us even as we are stringing him up.

After he did that, we discovered we could forgive others like he forgave us. As we forgive, we discover to our great surprise, that we are sharing in the life of God’s new age, or what we are used to thinking of as “eternal life.”

The text goes on. “Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God.” This appears to be the perfect verse to again set up a rivalry between those who believe and those who don’t. We may think we have a point of leverage with which to exclude. But the very next verse undoes this.

“And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil.” The judgment is people’s preference for darkness. It’s not God judging us at all. We are our own judges. We don’t look at the bronze serpent even though we have been bitten. To quote Michael Hardin, we refuse to take the red pill even though it is free.

The light is the brightness of God’s absolute compassion, God’s compelling non-violence revealed in Jesus but they turn away from it. They want their familiar rivalry and violence. They chose darkness and dislike light because they don’t want to see what the light exposes about the human species.

Our restless eyes must look up to find deliverance. When we look up, we are not focused on ourselves or our neighbor; our focus is on Jesus. He is not standing tall like a great teacher (This is the error many liberals make); he is lifted up on a cross. He is the very expression of God’s absolute compassion; the revelation of God’s compelling non-violence. As we look up to him, we, to our joy, discover God’s promised deliverance. Amen.