Can I Forgive?

Luke 15:11-32

As some of you may know, I am the eldest of five children. One of the best things about being a kid in a family with many siblings is that, if one were to, say, break a rule of the house (sneak into the snack drawer and eat a handful of cookies before dinner), there are myriad options for possible scapegoats. Occasionally my parents would line us up in a row and question us all together to get the answer to who caught a frog in the creek behind the house and put it in the mailbox, for example.

As some of you may know, I am the eldest of five children. One of the best things about being a kid in a family with many siblings is that, if one were to, say, break a rule of the house (sneak into the snack drawer and eat a handful of cookies before dinner), there are myriad options for possible scapegoats. Occasionally my parents would line us up in a row and question us all together to get the answer to who caught a frog in the creek behind the house and put it in the mailbox, for example.

One day, upon questioning us all to find out who the culprit was in the latest breach of family rules, my mother finally uncovered who did it. I can’t remember exactly who it was that time—I’m sure it wasn’t me—and the guilty party wailed: “I’m soooooorrrrrrry!” I’ll never forget my mother’s response. She said, “You know, sometimes sorry just isn’t enough.”

This week’s gospel lesson is about saying you’re sorry…and being forgiven…and not being forgiven. And it raises our Lenten question for the fourth week of Lent: can I forgive? You’ll recall that we’ve been walking through Lent together asking questions the gospel texts present to us; hard questions designed to help us do the work of living a holy Lent, questions that call us to rigorous self-examination, questions like: can I resist temptation? Can I give up my life? Can I admit I’m wrong?

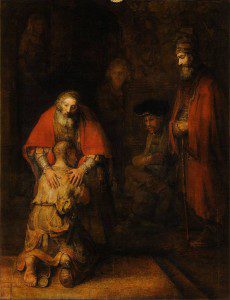

The passage from Luke’s gospel today presents us with one of the longest and most beloved parables in all of scripture, commonly known as the parable of the prodigal son. This is a familiar story to many of us, the subject of hundreds of years of beautiful and beloved art, and—most notably—a parable we can easily dismiss because it’s so familiar. Today our challenge is to look again, carefully and with fresh eyes at Jesus’ words as we ask the hard question to ourselves this week: can I forgive?

Recall, the Pharisees and the Scribes—the super holy religious folk—were grumbling, the text says, because Jesus was behaving in a way they found inappropriate: welcoming sinners and tax collectors, and even eating with them. In response to their criticism, Luke says Jesus begins telling stories:

Right before our gospel passage for this morning, Jesus starts his response to his critics by telling a lost and found story about a sheep—something all the men in that pastoral and agrarian crowd could certainly understand. A farmer has a flock of 100 sheep. One day he’s counting and he notices one is missing. So he leaves the 99 who are all still there, together, and goes out looking for that one missing sheep. When he finds the sheep that was lost, he celebrates.

When Jesus told that story I’ll bet he looked around and saw that people were engaged, nodding their heads, really understanding how a committed shepherd might go out into the wilderness, search for that one missing sheep, and celebrate upon finding it. And isn’t it nice that God loves us enough to search for us like that when we get lost?

But that’s not all he meant, and he could see they weren’t getting it…so Jesus tried again.

There was a woman who had ten coins. One day she notices one is lost, so she turns her house upside down and inside out, looking in every nook and cranny until she finds the coin that was missing. And all of the women in the crowd, who spent their days tending to homes and caring for families, would know what Jesus meant. And they would feel how relieved that woman was when she finally, after much effort, found the coin! She rejoiced and had a party, as God would do upon finding one of us, right?

They heard Jesus’ story about the coin and they got it. Hooray, God!

But Jesus looked out at the crowd again and he must have known, somehow, that they were holding the deep and personal challenge of this lesson at arms’ length. So, he tried one more time. And this time things got personal. Because it’s one thing to talk about finding a lost sheep or searching for a misplaced coin, but it’s another thing altogether to talk about people losing their way, and what it means to find and be found.

Let’s talk about human relationships, you might imagine Jesus would say, and let’s talk about the times when they get ugly and terrible. When someone hurts us and hurts us badly. When we need forgiveness and when we offer forgiveness and when we don’t. Shall we?

So Jesus tells a beautifully-layered, richly embellished story of a father, a respectable father not unlike those Pharisees and Scribes:

There was a father who had two sons. This was a good thing, since back in Jesus’ day it was imperative that you have at least one son to continue your blood line. The oldest son is the most important, of course, the second son like back-up. Insurance.

As the story goes, one day, the second son comes to the father and says he wants his inheritance. As we try to hear the parable again, we need to understand that back then, nothing passed from a father’s ownership until after his death—nothing. So asking for his share of an inheritance is akin to saying, “You are as good as dead to me!” One commentator likens it to Prince Charles, who upon being asked by the media about the possibility of his ascending to the throne of England replied, “Gentlemen, you are speaking of the death of my mother.”

In other words, the second son wasn’t just asking for an advance on the allowance, he was basically saying he didn’t value his relationship with his father at all. To that father, his son’s request must have felt like a punch in the gut—and everyone listening that day felt it.

But the outrage of the story continues, because after he’s given his share of the family’s assets, the younger son rushes off to seek his fortune in the big, wide world. He can’t wait to get as far away as he possibly can from his father and from everything his father represents. Gone. It’s the ultimate betrayal.

Lost sheep are one thing. Lost coins another. But this—this hits a little too close to home. The people listening to Jesus would have been rapt with horror, trying hard not to imagine anything like this ever, ever happening to them.

And I’ll bet Jesus finally got their attention by that point in the story. This was the worst slap in the face you could think of, and the father’s only recourse in the society in which they lived was to write that second son off as dead, to forget he ever existed.

Well, you know what happens next in the story. The father, strangely, is out on the road every single day scanning the horizon for that lost son, that son who had done just about everything a son could possibly do to hurt and betray his father and who, I think we can all agree, didn’t deserve that kind of treatment from his Dad.

And one day the father sees the son, who’s coming back because, frankly, he doesn’t have much of a choice—he needs to eat.

And the father? What does he do?

The father picks up his robes and runs—runs!—sandals flapping, dust blowing, all the way down the road to greet that son. He pulls him close and hugs him tight. He puts a ring on his finger and calls for refreshment. He brings him into the house and gives him new clothes and throws a party—the biggest party that little town had ever seen. That father had been waiting to welcome the son home, forgiven.

We could stop here and say: See? God forgives you and me like this. Right here, Jesus says yes. God loves you this much. God loves you so much that no matter how far you’ve gone away or how much you’ve hurt him or how little remorse you actually show in your desperation to return…God will take you back.

But like the distracted or dense crowd that day, we’re not listening very hard to Jesus if we think he’s going to let us off the hook that easy. We have to keep reading. Because there’s another character in this story who was also grievously wronged and does not run down the road with the excitement to join the party. It’s the older brother, the responsible one, who was left holding the bag of family obligations and the mantle of his father’s expectations all by himself. Not fair! “For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, never once disobeying. He comes back and you throw a party. I stick around and do what I’m told, and I get no appreciation whatsoever.”

And it’s right here that we can stop for a moment to suggest that maybe this parable is not really a story about a wayward son who decides to come back home.

Perhaps this story isn’t even really about God forgiving us.

Did you hear me?

This is a story of two people who are terribly, horribly hurt. Wronged. Outrageously. One of them forgives, and one of them doesn’t. Can you forgive?

You’ll notice when the prodigal son returns home that the father doesn’t make some big announcement about forgiveness; he doesn’t really say anything to him. He just embraces him and throws a party. The older son, though, stays bitter. Angry. He isolates himself, licking his wounds and tallying the fairness of it all. He didn’t know my favorite quote from Anne Lamott: “Not forgiving is like drinking rat poison and hoping the rat dies.”[1] Forgiveness isn’t formulaic; it’s not a magical pronouncement. It looks different in different situations. But fundamentally forgiveness is the hard internal work of those doing the forgiving.

Human relationships are messy things. There’s not much about our interactions with each other that is unfailingly fair or loyal or loving. People let us down, even sometimes the people we trust the most. But our choice to forgive or not forgive the wrongs done to us doesn’t really impact the people who have hurt us. It impacts us. If we need a reason to forgive this is it: we forgive to be free.

I spoke this week with Father Michael Lapsley, close friend of this church and many of us. “Father Michael Lapsley is a former South African anti-apartheid activist. In 1990, three months after the release of Nelson Mandela, the ruling de Klerk government sent Father Lapsley a parcel containing two religious magazines. Inside one of them was a highly sophisticated bomb. When Lapsley opened the magazine, the explosion blew off both of his hands, destroyed one eye and burned him severely.”[2] Father Lapsley now works to help victims of terror to heal.

As I was thinking about what it takes to forgive this week, I got in touch with Father Lapsley to talk a little more deeply about his thoughts. He reminded me that the Greek word for forgiveness means something like: to let go, to loosen, to release, to untie a knot. That word is not found in Luke’s text today, but it’s message certainly is—stated strongly and clearly by the one who, beaten and hanging on a cross prayed, “Father, forgive them.”

Can you forgive? It would be nice for the person who hurt you if you could, but as my mother said: sometimes sorry is not enough.

Remember why Jesus was telling the story. He was confronted in that moment with self-righteous zealots; religious folk who pretended that they were perfect by maintaining a slick façade and dismissing those who didn’t meet their standards. But…everybody needs forgiveness, because everybody makes mistakes. It’s when we close our hearts to forgiving others that we find we cannot forgive ourselves.

Jesus looked around at the Pharisees and Scribes who wore their rules and their outrage like a fancy garment and spent all their time grumbling, complaining, and damaging relationships. Jesus wanted them to know that it’s the courage to forgive that makes your heart open to all the possibilities of life together, not the clinging to rules and the dismissing of others. The refusal to forgive leaves you hard and fractured and alone.

It’s true: forgiveness is hard, but who would you rather be? Open and loving, or hard and closed? It’s your choice.

Today our Lenten question won’t let us rest until we look hard inside and ask ourselves: can I forgive?

[1] Anne Lamott, Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith.

[2] http://www.democracynow.org/2013/4/22/apartheid_regime_bomb_victim_father_michael