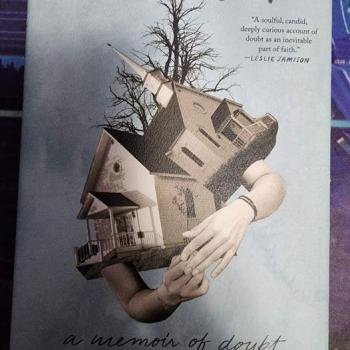

The book “Faith After Doubt” was authored by Brian McLaren, and released in the year 2021. There were a few reasons I opted to read this book in reference to my deconversion studies, one of those being that McLaren seems to be offering this book as an alternative to “deconstruction,” a popular term for exiting Christianity. As the book title suggests, McLaren is offering an alternative form of “faith” that includes doubt.

The Emergent Church Movement

Brian McLaren is a pastor and founder of the Emergent Church (EC), a movement that began around the turn of the century. Listening to McLaren and other Emergent leaders, it becomes apparent that the EC phenomenon was the same thing back then as the current Deconstruction Movement (DM). However, whereas the DM is pushing toward an irreligious result, the EC sanctifies doubt, spiritualizing the process of Deconstruction as a sort of religious practice in its own right.

Both DM and EC look at things like religious politics and Biblical problems and respond with the same criticisms. However, whereas DM resolves these difficulties by concluding that Christianity is wrong or bad, EC looks to indefinitely extend the process of Deconstruction as a sort of religious ritual.

The Definition of “Doubt”

Early on in my investigation of deconversion, I tried to see what kind of psychological research had been done on the subject of “doubt.” I assumed that if we knew how doubt worked as a general concept, we could make specific applications to religious doubts.

I was surprised to find that psychology didn’t even touch the subject of doubt anywhere but in a religious context. All the studies I could find on doubt were on religious doubt specifically. To Psychology, doubt has a very religious connotation – much like “faith.”

Brian McLaren’s book has helped me to home in on the issue. McLaren’s definition and description of religious doubt helped me realize that psychology has been studying doubt for a very long time under the umbrella of “dissonance.” McLaren defines doubt as “being of two minds.” The definition of cognative dissonance is “the discomfort of holding two contradictory ideas in tension with one another.”

McLaren and “Mental Modes”

In chapter 2, McLaren begins talking about three “mental modes” which he divides into gut (intuition), heart (emotional), and brain (analytical). McLaren is not a psychologist, and he is writing to a general audience, so I have to admit, I find this section to be a bit reductionist and condescending, however more informed researchers than he have made similar breakdowns in three pathways in the deconversion process.

One study in particular, “Digital Irreligion”(2019), breaks the drivers of deconversion down into three categories:

- Moral (or emotional) objections to Christianity (related to things like unethical content in scripture or exclusivism within Christianity)

- Intellectual problems (science and the Bible, etc.)

- Personal Growth (the religious environment is constricting or restrictive, and leaving it is necessary for growth or freedom).

McLaren has managed to stumble upon something researchers have elsewhere recognized: that objections leading to deconversion do tend to be equally social, emotional, and intellectual.

Profiting from Religion

McLaren says that he, as a pastor, was “paid to believe.” The point being that the cost of disbelief was high, but that the motivation for belief was insincere.

In his book Drive, psychologist Daniel H. Pink shares research that suggests that when a person performs an activity for the satisfaction of that activity (as with a game or hobby), the enthusiasm for the activity is high. However, if a person is paid to do something they find enjoyable on its own, the intrinsic enjoyment is removed.

In other words, if an artist suddenly gets paid to produce art, the act of creating becomes less enjoyable when the motivation is pay.

McLaren, as with most deconverts, underwent an “intensification experience” in adolescence when his religion suddenly became very intense and important to him. As with most individuals in this situation, he turned his passion (Christianity) into a career (Ministry).

McLaren struggled with all of the difficulties that come with ministry – funding, constant criticism, dealing with other people’s problems along with his own, being booted from church to church – and eventually came to realize he was offering something he didn’t believe as a solution to others. But he was being paid to believe, and had to keep it up.

Pink’s research may help to explain why unpaid individuals with private ministries are so dogged in their beliefs (they are working for the passion), while most deconversions are seen from professional ministers (they are working for the pay).

Stages of Faith

In chapter 6, McLaren begins to lay out his “stages of faith” which form the thesis of his entire book.

This is the point at which reading popular-level books for research becomes difficult. If McLaren is drawing his conclusions from research-based methods, he does not outline the methods or do anything resembling rigorous argumentation or citation. He makes broad “this-is-how-it-is” statements illustrated by anecdotal accounts with the expectation that the reader will accept his model on power of assertion alone.

In other words he is arguing like a pastor, not a researcher.

McLaren begins by saying that he began researching developmental psychologists on his way to forming his model, which is a good start, I suppose. He begins his list with Freud and Jung, which won’t win him the academic cred he might expect.

He then makes certain to let the reader know that he expanded his reading after realizing that all the researchers were white Western males.

Again, this concern about the identity of the writers as opposed to methods and sources raises concerns about his conclusions: he seems to be assuming that it is the author rather than the methodology which lends credit to the source. This bears echoes of the very method he is arguing against: that religious people accept religious doctrines on the power of authority rather than investigation.

The value of McLaren’s book to me as a researcher is that it contains some autobiographical and biographical elements which provides data I may integrate into my own model. His observations and conclusions aren’t entirely unhelpful, but given that he is writing what amounts to a self-help book for people who, like himself, have undergone faith crises, I am cautious about swallowing his conclusions.

McLaren’s “Four Stages of Faith” appears to be a model built on his personal experience as well as the people like himself with whom he has interacted. The book was written at the popular level, and so no attempt was made to describe his method for developing the model. He claims to have read extensively in psychology, however he cites little or no research as he develops his stages.

In his defense, however, he isn’t claiming to add to the body of research or to expand the social sciences. He makes it clear that he is in the business of offering mental and emotional relief to people who, like himself, have suffered a crisis of faith.

A brief description of his stages are as follows. I am using his titles, here:

- Simplicity: a sort of black-and-white, dogmatic way of thinking, wherein every doctrine is either right or wrong and there is a high level of certainty on the nature of one’s beliefs.

- Complexity: a more nuanced way of approaching doctrines in which one explores different methods of viewing issues. McLaren also says that this stage involves developing models and methods, such as “Four Ways to Improve your Marriage,” or “Seven Ways to Pray Effectively.” I found this piece to be somewhat ironic considering his “Four Stages of Faith” contained all of the earmarks of these systems he described.

- Perplexity: This is the stage at which the “Deconstruction” experience occurs, when all of the ideas in the previous stages are viewed with skepticism, picked apart, and found to be lacking.

- Harmony: Not standard to the deconversion experience, McLaren suggests that after one has been disillusioned by the previous three stages, this person may experience a sort of Zen state by embracing the doubt and living in a state of uncertainty. This is the “Faith After Doubt” to which he alludes, and probably the basis on which he built the “Emerging Church” movement in the 2000s. McLaren concludes his book by suggesting that one can find Harmony in a state of total expression of Love, whereupon the only item upon which faith is developed is Love for one another.

Reflections on McLaren’s Model

The author’s model is not constructed in a way which has any obvious method behind it, and appears to be the product of the more self-help/counseling background which attempts to create some superficial structure into which one can read their experience. These models work so long as a person can find meaning in them, but are not helpful for behavior modeling.

Stage one of McLaren’s model does contain features which I have identified in my research, most notably “Compulsory Certainty.” This is a dogmatic approach in which one must maintain a high level of confidence in one’s belief system. When that confidence is challenged or collapses, it becomes a stressor which contributes to deconversion. The “complexity” and the “perplexity” states, as McLaren describes them, might as well be fused together in my work as follows:

When a person’s confidence is challenged, the person enters a state of dissonance (what McLaren calls “perplexity”). This dissonance can be resolved by finding a new model in which they may place confidence. But upon finding the new system, the degree of confidence the person has is diminished by their previous experience, and that confidence is more easily challenged such that the person’s likelihood of entering a state of dissonance is higher. As this process repeats itself, the person is less and less likely to establish a state of confidence or certainty, at which point the system disintegrates and deconversion occurs.

McLaren never properly deconverted in the sense that he no longer believes in God or adheres to religion. Instead, he has adopted a form of religion based on action in which the only doctrinal substance is that it is moral to love one another. In this sense, he is something of a Universalist, without necessarily believing in an afterlife (nor denying that such a thing exists).

Ultimately, this book added little insight to the existing research but did, in some ways, confirm some of the basic findings in other research as mentioned above. McLaren is simply doing what he has been doing for the last 20 years, and trying to provide a space in which a person may comfortably remain both spiritual and also skeptical. Wherein they may have some basic religious ideals, but avoid rituals, doctrines, dogmas, and authority structures associated with organized religion.