by guest writer William M. Shea, Ph.D.

“If You Understand It, It Isn’t God” [1]

Augustine, bishop of Hippo in North Africa (c.400 CE), wrote: “If you understand it, it isn’t God.”[2] What a statement from a man who many think is the greatest theologian in the history of Christianity. No wonder, then, that there are atheists. In general, atheists want to understand. Given that desire, it seems perfectly logical that atheists would take Augustine seriously and give up on knowing God and stick with what can be understood, that is, what falls within the horizon of possible human experience, for surely what is and can be understood is subject to human understanding. God isn’t. Why would any of us go on a quest to understand what even a leading believer reports as beyond “comprehension”? Why wouldn’t they look at believers as wasting time in their continuing quest to know God? And I mean believers as a whole, for all of them face pain, evil and death and do not understand but only accept in the “leap of faith” that for which there is no empirical evidence. In fact atheists dare believers to furnish evidence, any evidence, confident that their position is unassailable. And so it is if the inviolable limits they set to understanding are correct. Believers paradoxically seem to think that God is so evident that there is no need for the atheist’s preferred evidence and go right on blathering about nothing!

One strand of atheism has an attractive solution to this conundrum: believers do speak meaningfully and valuably but they make a category mistake in interpreting their religions’ claims. In effect, religious practitioners take beliefs as asserting facts about the cosmos and miss the point: religions express ideals, values, not reals. Religions are a product of imagination rather than understanding. Religions are based on projection, not on empirical evidence. There are many such atheists, among them my favorites: Ludwig Feuerbach, George Santayana, John Dewey, and the American Naturalists Frederick Woodbridge and John Randall. Even Karl Marx meant to affirm that religion served a purpose when he wrote in The Communist Manifesto that “religion is the opium of the people.” The people need that opium given the conditions under which they are forced to live by capitalists!

The British philosopher John Gray recently published a fine critique of the work of his fellow atheists in which he often leans in the direction of this first group. The title is Seven Types of Atheism. He sprinkles the term “mystery” in his concluding chapter and ends by saying that atheism and the religions have more in common than they think. I interpret him to mean that the terms “mystery” and “Mystery” overlap in their intention. That opens a door to “encounter,” does it not? What exactly do we mean when we use the terms mystery/Mystery?

Formal arguments for the existence of God (e.g., Aquinas’ famous five) are meant to help those who believe. Aquinas’ discussion in the Pars Prima owes much as we would expect, to Aristotle, but also too elucidations by Jewish and Islamic thinkers. The arguments fail those who don’t believe chiefly because of the cognitional suppositions underlying belief are not in place for them. Where there is an opening to transcendent knowledge arguments may help.

Of course, where there is belief there is doubt.

Doubt is part of the desire to understand. Questioning, the quest for meaning, is the promising spur to the reflections of philosophers and theologians, and the challenge to the faith and belief of the poor and the suffering. That quest is the root of all religions as it is of philosophy. Atheists as well as believers are trying to understand religions or their religion. Atheists reach the conclusion that there is nothing to understand. Some of them add another judgment that religion is an aberration of mind and spirit, even, as Dawkins famously said, an “abuse of children” as if my education in Catholic schools and at home was a poison poured into my mind and my parents were abusing me when they taught me to pray. From believer’s point of view, educating children in atheism, especially the New Atheism, is an abuse, a poisoning of the mind of children. The New Atheists (Hitchens, Dawkins et al.) have placed themselves beyond civil conversation by their attitude toward religions.

Other atheists go a good bit beyond The New Atheism and regard religion as a perfectly natural activity, perfectly human, understandable in anthropological and sociological terms (much like politics) but often misunderstood by practitioners who seemingly take religion to involve a description of the cosmos or, worse yet, an explanation of it. And so the arguments continuously play out not only about whether the “IT” is real, but also about what religion is as a practice, what are religious people doing and what they are talking about. There are three large issues at stake, then: (a) Is God?; (b) What is God?; (c) What good is religion?[3] The first two of these questions will be taken up in the next post.

___________________________

[1] I have been taken in by what our President calls “fake news” and “a hoax” and I must apologize to the readers of my last post, “Atheism and Theism.” It is not true that the Icelandic parliament named religion a mental disorder. Mea culpa! The essay was intended as satire and posted on patheos.com. The author is Andrew Hall.

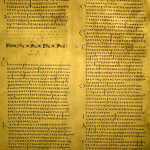

[2] “Si enim comprehendis non est Deum.” Had I been a Bishop in the church I would have put this in my coat of arms. God is not a thing.

[3] Google “religion and sex.” According to recent sociological research couples who are religious practitioners are more satisfied in their marriages and have better sex lives than couples who are not. I once presented this inspiring thought to a class, one member of which raised his hand and said: “Where do I sign up?” Pay attention, you atheists!