“There are no nice Nazis!” said Senator Bernie Sanders at a town hall meeting in Detroit, responding to Trump’s equivocation in regards to the violence in Charlottesville.

I wish I could agree with him. It would be so much easier to identify those who support genocide, if they were all menacing cartoon villains, or sterotypical skinheads. Unfortunately, however, many very nice people have been Nazis, Fascists, and Neo-Nazis. This was true in Germany and Italy in the Thirties, and it is still true today.

For one thing, “niceness” alone is no guarantee of goodness. To be nice, to conform to certain standards of propriety and respectability, can be pleasant, but it is an error to confuse superficial propriety with true kindness or virtue. Virtue may require us to behave in ways that are not in accordance with respectability, to defy the oppressor, to go in among the outcast. It may involve breaking unjust laws, and putting the dignity of the person above contrivances of social order.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that anyone is justified in behaving disruptively for any reason, or that social codes can simply be dismissed because one feels too important or is too lazy to defer to them. The iconoclasm of a Donald Trump who sneers at political correctness – political correctness that exists, ideally, to protect the vulnerable from bullies – is on the far end of the pole from the iconoclasm of social justice activists who take risks in challenging unjust systems.

But typically, nihilistic iconoclasts such as Trump draw their cover precisely from the ranks of the “proper.” We see outcries against leftist activists from many who gave a pass to pussy-grabbing, because it is necessary for enablers of fascism to clarify that they are on the side of “law and order” and “propriety.” As the defenders of such, of course, they also get to decide when a breach of courtesy is permitted. “It’s just a fault of style” I heard, from one reluctant Trump supporter.

There’s been a lot of talk about how the immorality, crudeness, and even stupidity of the Trump regime is, for a class of his fans, not a bug but a feature. National Review columnists may lament the unruliness in the White House – and we all say, “look, even these conservatives get it, now.”

But what are they really lamenting? Their issue really is simply with a level of style. Their complaint is, essentially, that all the crassness and in-fighting are preventing their president and his cohorts from effectively cutting our health care, deporting immigrants, and creating tougher laws for cracking down on vulnerable populations.

These respectable ones are, perhaps, cause for greater moral concern than the brash and newsworthy man in a MAGA hat, screaming racial slurs. We all see that he’s bad news. What we don’t see if that the nice ones may be worse news.

Niceness is not goodness. Niceness may even provide cover for evil. As Joseph Brodsky said: What we regard as Evil is capable of a fairly ubiquitous presence if only because it tends to appear in the guise of good.” Think of how many in the American South accepted slavery as a social good, and viewed as renegades those who would upset what they saw as a God-givn order. How quickly people will evoke the “rule of law” as an excuse to condemn refugee children to starvation, and death by drowning.

When Trump says there are “fine folks” on both sides, I am reminded of how easy it is for evil to be normalized. I am reminded of Hannah Arendt and her report on the trial of genocidal Nazi mastermind Adolf Eichmann. The Banality of Evil, she calls it – that evil doesn’t come sweeping in, in a black cloak, masterful as Sauron or Voldemort. It doesn’t have vampire teeth and maintain a witchy lair. All of these things are glamor, glamor borrowed from beauty, whereas evil itself – as Augustine also noted – is a nothingness, an emptiness.

Arendt writes:

“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.”

That evil can be decent, polite, and normal is indeed terrifying, which is perhaps why we love our fantasy and superhero stories in which the villains are, once unmasked, given to sinister chuckles and addicted to bizarre fashion. We worry about people being “radicalized” – but Arendt points out that evil is not radical. Extreme, yes, but there is no depth to it. One need not decide to become evil, as does Milton’s sympathetically-portrayed Lucifer. The degeneration into evil happens for the most trivial reasons, in a bourgeois middle-class manner, in nice well-kept neighborhoods.

I have two take-aways from this. One is political. We need to think less about what is respectable and legal, more about what is genuinely true and good. We can’t trust niceness. “He’s a very nice man” is no reason to think someone isn’t politely permitting genocide, or even plotting it. People may tend their lawns, love their pets, and dress their children nicely while supporting intrinsic evil. If they think that their power or prestige are threatened in any way, they may behave dishonorably – for some nebulous “greater good,” and they will do it while posting lovely little quotations on Facebook. And most likely, at some point, they will say ‘I’m praying for you.”

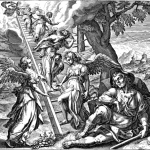

The other is personal. It’s not always just “they.” It’s we. We need always to be on guard against accepting the popular or the normative as the good. I need to be wary of cultivating in myself a series of poses intended to project a goodness I do not have. Standing up for humanity may not win one any awards. It may mean loss of resepctability, of income, even of life. And, unfortunately, defending the innocent probably isn’t going to look epic and glorious, like riding in on dragons. Riding in on dragons comes with a whole other set of temptations, anyway. Evil is always waiting for an inroad, and for those of us who find respectability boring, and have no interest in well-kept lawns, our temptation may be to set ourselves up as heroic or Messianic figures – forgetting the true Savior of the World, who didn’t save us by riding in on a dragon, but by going out on a cross.