I went to the Wildflower Reserve, to see how the world was going to sleep.

I can’t even begin to tell you how I’ve longed for a hike this whole miserable summer, and now the summer is over. The garden that took up so much of my attention is nearly all dead for the year. The sickness that lingered for eight weeks is behind me. Serendipity, that horrible black flood car that died a terrible death in June, is in her final resting place at the junkyard down in Mingo Junction. I already spent the two hundred fifty dollars cash that was all she was worth. Now I’m driving another ugly Nissan, a blue one this time. I gave it a mild expletive for a name in the hope that that will be luckier than the bad luck car named Serendipity: the blue car’s name is Sacre Bleu.

When I crossed the Veteran’s Memorial Bridge, over the Ohio river and into the chimney of West Virginia, I felt like a convict being sprung out of prison.

Whoever owned Sacre Bleu last fitted her out with an excellent stereo. I sang along with the radio at the top of my lungs, from the West Virginia border to the Pennsylvania one and out to the Burgettstown exit, down PA 18 through the prettiest farmland in the world. I’ve taken that road so many times I could probably drive there in my sleep, and then I’d been deprived of any drives for fourteen weeks straight.

Last year on this exact day I also went hiking, and I was so sad.

Today, I was happy. Oh, part of me was anxious about everything and part of me was sad and angry about everything. I am always sad and angry and anxious and I suppose I always will be. But I was also overwhelmed with happiness. I felt wonderful. I was free after being grounded for months and months.

We’ve reached Peak Color in Northern Appalachia. The hills will be on fire with bright gold and scarlet until after Halloween. Everything is bright and clean and crisp and colorful as if it were a painting and not real life. When I finally parked at the Wildflower Reserve, I was sad the drive was over, but when I got out of the car, I immediately forgot everything.

There are barely any wildflowers this time of year, but the trees make up for it. Over and over again I craned my neck to look up, lost in beauty.

As I hiked, I prayed. I always do. I can’t not pray when I hike, and it’s hard to pray when I don’t hike.

Uphill, huffing and puffing because I’m so out of condition. Why did you do this to me, God? Why did you abandon me in Steubenville all alone? Why did you make me so different from everybody else? Why do you hate me so much?

Emerging at the top of the hill, gasping for breath, looking up at those trees again. Because of the Lord’s great love we are not cast down. Great is your faithfulness. Thy mercies are new every morning. Great is your faithfulness. You must have loved me so much, to make trees like this.

Downhill, clumsy as ever, staring at my feet so I wouldn’t trip, in a cacophony of crunching leaves. In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, amen.

I would’ve been such a good Catholic if I could have been a different person in an entirely different era: a person strong, healthy and male enough to be some itinerant friar wandering around the countryside outdoors all day, preaching the Gospel to any peasant or leper or white tailed deer who happened along, back when that was what some people did. As it is, of course, I am only me, a failure.

The path wound around by a river that I wanted to jump into. I was deprived of swimming outdoors in the sunshine all that long, tiresome, agonizing summer, and it tortured me. But now it was far too cold for that.

I found a great big smooth tree leaning over a river, and leaned on the trunk in turn, and watched the water go by underneath me: clean, sparkling, the bottom a mosaic of broken shale, the surface all glinting light. If my arms had been long enough, I would’ve at least let it drench my fingers.

Great is your faithfulness, said the river. Great is your faithfulness. Great is your faithfulness.

I have been so sad and so afraid for the longest time. It took until I was forty to be even close to happy, and I’m still not very used to it.

I could have been such a good Catholic if I’d never been out to Steubenville and discovered how wrong I was about everything. But now I’ve been living in Northern Appalachia for almost as long as I lived in the Midwest, and I like it. I like it all except for the wrestling with what to do with my faith.

I kept hiking, under trees so tall I nearly fell over backwards when I craned my neck to look up at them. The yellow oblong leaves against the clear blue sky were dazzling.

I found another root extending far over a patch of water, and watched the river go by again.

Vidi aquam egredientem de templo, a latere dextro, Alleluia: Et omnes ad quos pervenit aqua ista, salvi facti sunt, Et dicent: Alleluia, Alleluia.

I like the person I am becoming. I like the way Adrienne is happy now, in this new life, at the public school instead of a prim Catholic homeschooler. I like the work I do with my writing and the places I can go in the car. I even like my neighbors. But I don’t like this feeling that I’ve failed God.

I am not better than the people who don’t believe in God. But, in spite of everything, still believe in God, and what’s more, I don’t want to not believe.

I am more and more convinced that there must be a God, and that that God must be just and merciful, that one of the things that is true about God is the dogma of the Holy Trinity, and I’m still deciding what that means for me.

But I’ve failed at being a good Catholic. And I can’t ever go back to what I was, before I came to Steubenville and learned all the terrible things that I know. I can’t cure my complex post-traumatic stress disorder. I can’t participate in the sacraments, so much of the time. I can’t stand to pray the Rosary or sit in the Adoration chapel. I still can only go to Sunday Mass if I stand in the back and take frequent breaks to pray on the church porch in quiet. And I honestly don’t know if I could ever go to confession again. I can’t go into a box with a priest by myself, ever again. The thought of it makes me sick. But I’m also sick at the thought of how long it’s been, and what’s going to happen to me when I die in this state.

I rounded a corner past Shafer’s Rock, a great big jutting cliff of Ohio Valley shale, where God had shown me those beautiful flowers last spring.

I ascended the final part of the trail and climbed to the top of that rock.

There’s a piece of wooden fencing on bricks at the top of Shafer’s rock, with a sign on it that says “not a trail” so nobody walks right off the edge of the rock and plummets to the bottom of the wildflower reserve. Every time I see it, I think it looks like a kneeler at a communion rail, or in a confessional.

I wandered over to lean on the fencing, as close as I dared to the edge of the cliff.

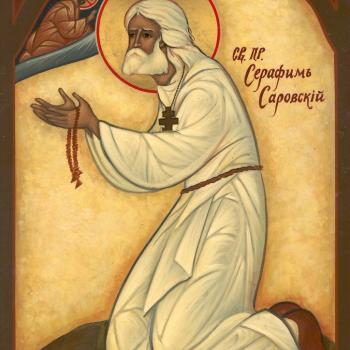

I folded my hands at the rail like a good Catholic.

“Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned,” I said to the Father, in case He was listening.

I wished there was a priest there, one who wouldn’t trigger my panic in the least. And then I remembered my catechism about Jesus the Prophet, Priest and King. I pictured Him standing among the trees on the other side of the rail, looking a bit like Elrond.

I confessed all of my sins, as best I could, counting the ten commandments on my fingers and using all the silly mnemonics I taught myself in my Confirmation classes when I was Adrienne’s age. In the places where I honestly don’t know what’s a sin anymore, I said I was sorry for anything I’d done on purpose or by accident, begged Him not to hurt me for doubting the Church if that angered Him, and asked wisdom to know right from wrong.

I stated my contrition as best as I could. When I got to the part about “confess my sins, do penance, and amend my life,” I started to panic.

“You know I’m not doing this on purpose,” I said. ” You know I’m trying. I wish I could do what I’m supposed to do, but I can’t. I didn’t do this to myself. What hurts the most is that the people who did this to me, did it in Your name. And I’m afraid You are the one that did this to me. But I’m trying.”

I tried to imagine Jesus forgiving all my sins in the Name of the Father, and of Himself, and of the Holy Ghost.

I forgot my panic as soon as I turned away from the rail and looked at those beautiful trees.

By the time I got back to the car I was almost completely happy again.

I was almost happy all the way home.

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross, The Sorrows and Joys of Mary, and Stumbling into Grace: How We Meet God in Tiny Works of Mercy.