There was a girl at our church who had cancer.

I don’t know why I’m thinking about this right now, twenty years later, in January, during a pandemic, while my own daughter shovels the walk. The dark of winter is a good time for telling stories, so maybe that’s it. I’m just telling stories. Yesterday I told you about the mudpuppy that taught me compassion, and now I’m going to tell you about a girl who had cancer.

The girl was about eight years old. She was a middle child: there was also a pre-teen daughter and a plump baby. By the standards of our parish, that was a suspiciously small family, but this couple was open about their fertility struggles so we supported them. Back then I didn’t see anything strange about being suspicious of a couple with only three well-spaced children. It was ubiquitous in our social circle to admire people who conceived often, console people who couldn’t conceive, and hate people who wouldn’t conceive. So this family was loved.

One day, the middle child started crying that her stomach hurt. They saw that it was bloated and rushed her to the emergency room, suspecting appendicitis, but it wasn’t: it was a great big tumor on her kidney. The doctors removed it that night. They said it was a very common form of childhood cancer, incredibly treatable. The child had nearly an eighty per cent chance of never having cancer again, if they were aggressive enough in treatment. And the treatment involved a lot of chemotherapy and radiation.

Can you imagine putting an eight-year-old girl through chemotherapy and radiation?

The parish rallied around the family, bringing meals and arranging babysitters. I loved that about our parish. Even now, knowing what I know and deconstructing an extremely toxic religious practice which has traumatized me, I still miss that aspect of having a close-knit and insular religious community. I miss the camaraderie. I miss the way everyone would pitch in and help with no question, when a family was in crisis. I volunteered to pitch in as well.

My job was to be an understudy: I was come to the hospital and help watch the baby, while the father was at work and the mother was in the chemotherapy room with her middle child, if the usual babysitter couldn’t make it.

Have you ever been in the waiting room of a children’s chemotherapy center?

It looked about like the waiting room of any other children’s medical facility. There were bright colored walls, a magazine rack, and a television blasting The Wiggles. There were children sitting with their parents, watching television. There was a candy machine and a soda machine. I could have been tricked into thinking I was just at the pediatrician or a dentist’s office. And then I noticed that the bald toddler sitting next to his mother watching The Wiggles was not actually not a toddler. He was about six. He had no hair. His skin was an odd shade of yellow. Next to him, a few chairs down, was a little girl about nine, skinny as a skeleton, retching into a bedpan. Further down was another sick boy without hair, asleep.

After taking in the skeletal children, I saw the mother rocking the baby. I didn’t see her child waiting for chemotherapy, at first. But then the mother called her name.

The girl’s skinny bald head peeked out from her hiding place between the candy machine and the soda machine.

“I have seventy-five cents in my hand,” said the mother, proffering the coins. “You can get a treat from the machine if you want to. But the mask has to go on.”

The girl slid out from between the vending machines and sulkily took the blue surgical mask and the money. “Why do I have to wear the mask?”

“Because I’m the worst mother in the world.”

The girl had nibbled a bit of her snack before it was her turn to go back to the infusion room. Other children weren’t allowed in the infusion room. The mother left me with the baby, who didn’t like strangers, and howled for the next hour.

The family had to go through this once a week.

Their daughter was unbearably sick all the time. She was too weak to even hold her baby brother, and she couldn’t go out without the detested mask. She held up incredibly bravely, but once in awhile she broke down and had to be sedated or she couldn’t have gotten through all the treatments. The mother breastfed the baby and tended the sick child day and night with no rest. The father worked at his job and couldn’t be home when he wanted to. The older daughter stayed home like Cinderella doing far too much housework because she was the only one to do it or it wouldn’t get done. Their house was a clean sterile fortress with “please wash your hands!” signs on the front door. No one ever got to have any fun. And all the while they knew this wasn’t guaranteed to work. It might all be for nothing. She might still die.

One day, after Mass, I saw the mother chatting with a devout old church lady by the baptistry.

“They’ve started her on radiation,” said the mother, balancing the baby on her hip. “They say that radiation makes it much less likely to come back. She’s taking it pretty well. But… they did warn us, right from the beginning, that radiation has a fifty per cent chance of sterilizing her. She might not ever be able to have a baby.”

“Oh,” said the church lady, her face a picture of sympathy. “That’s terrible. Do you know if convents take girls who are sterile?”

The mother looked confused. “I think so?”

“Ah,” said the church lady, smiling. “Good. It’s good to know that that will still be an option.”

I cannot describe to you how deeply brainwashed I was at that point in my life. I was ultra-conservative. I questioned nothing. I thought the whole world around me was in a demonic conspiracy against my Faith. I thought feminists were evil witches who murdered their babies. Most every grown woman I knew was either a multipara or a religious sister. I wanted to be a multipara or a religious sister, as long as I could also be in Shakespeare plays. And yet I was furious.

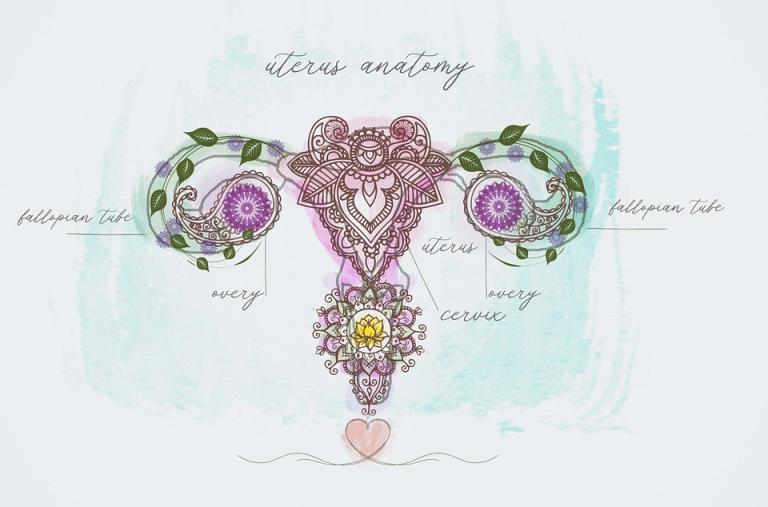

Here was an eight-year-old girl fighting for her life– a whole family fighting tooth and nail for an eight-year-old girl’s life. And here was a self-righteous lady writing the girl off as ruined because her ovaries might not work properly someday. Here was a church lady relieved that they might be able to dispose of that ruined girl in a convent. That’s what a little girl was for after all: to grow into a woman and get pregnant, or to vow never to get pregnant. To fill that uterus as often as possible or to keep it an enclosed garden for the Lord. Men exist for God and for themselves. Women exist for the pear-shaped sack in the middle of their abdomen. Boys have lives ahead of them and girls have babies.

I wanted to scream, but I didn’t. I didn’t react at all, outwardly.

The girl finished her treatments. She was declared cancer-free. Her skin stopped looking so pallid. She grew plump, and her hair grew back. The baby grew to be a toddler. The tired older sister became a teen. After awhile, I left Columbus and never heard from them again.

I didn’t think about them for the longest time.

Now I’m 37 and struggling with secondary infertilty from my PCOS. My daughter is nearly pubescent, and she’s given up hope for a sibling. She is a brilliant, active tomboy who wants to be a park ranger when she grows up. I live next door to a madwoman dying by inches from cancer. People I trusted to teach me what God wanted have proven untrustworthy a thousand times over. I no longer trust them to inform me what unloving things a God of Love demands that I do. And I can’t get that story out of my head.

The family, struggling to have children. Us, reluctant to accept someone who didn’t have enough children unless they had an excuse. All the help and support we gave, to our own approved in-crowd. The desperate fight to save a child’s life. The withered wizened little ones in the chemotherapy waiting room. The exhausted woman saying “because I’m the worst mother in the world.” The little girl who won an eighty percent chance of not being eaten alive by malignant tumors in exchange for a fifty percent chance of sterility. The horrible pious woman asking if convents took sterile girls. The moment when I realized I belonged to a culture that did not value women except for our fertility, but I was too shy to scream.

Do they take girls who are sterile?

Does anyone take girls who are sterile?

Does Heaven above love girls who are sterile? Does Heaven love girls who are bald? Does Heaven love girls who retch into bedpans and fall asleep in the chemotherapy waiting room, who hide between vending machines because they are scared of masks? Does Heaven love couples who struggle and strive and still can’t have a big family? Does Heaven love babies who cry for an hour when they can’t find their mothers? Does Heaven love mothers who bribe their sick daughters with candy and sigh “Because I’m the worst mother in the world?” Does Heaven love girls who stay home like Cinderella because the housework won’t get done if they don’t, and parents who can’t get home from work when they mean to? Does Heaven love people who don’t fit into the in-crowd and don’t have a conservative insular church to fawn on them?

Yes, Heaven loves us all.

Heaven does not have rigid boundaries determining who Heaven loves. Heaven will take anybody who wants to be taken on that journey. I am still learning what that journey is like, but I believe it will end in happiness.

The spirit of the world loves girls for the pear-shaped sack in the middle of their abdomens. Heaven loves girls because girls are people.

The spirit of the world insists that people fit into rigid categories and do what they’re expected to do. Heaven just loves.

And if I’m wrong and Heaven doesn’t love, then Heaven isn’t worth my time.

I have not seen that girl in over a decade and a half. I hope she is still alive.

And much more importantly, I hope she is happy.

Image via Pixabay

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross and Stumbling into Grace: How We Meet God in Tiny Works of Mercy.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.