I went for a hike by myself.

When I was a teenager I was told not to go on hikes by myself because “you might break your leg and die,” but I didn’t listen. I wandered off from my family at those strange reunions up in Pocahontas County, to have peace and quiet by myself. This was considered one of my eccentricities and a sign that I wasn’t all right. I was supposed to like staying at the party with my cousins who thought it was funny to tease me until I cried, or my aunts who never listened, or my mother who was deeply ashamed of how ugly and awkward I was.

One year, I remember, I was washing my hands at a sink in one of those glorious old log cabins at Watoga State Park, when the sink somehow slipped right out of the wall. The plaster or whatever it was that connected the sink to the pipe at the back of the wall had crumbled apart, and when I pulled on the handle to turn on the hot water the whole thing slipped forward out of place. I held the sink up with my knee so it wouldn’t shatter on the ground. I yelled for help, but the relatives talking and laughing in the next room didn’t come to help. They were standing mere feet from the thin door. I knew they could hear me, so I yelled louder. They raised their voices to keep talking and laughing. I yelled louder still, but they continued to ignore me so that whatever the problem was, I would stop making a fool of myself and be quiet. Eventually, somehow, I managed to shove the sink back into place, and then I stormed into the living room to yell at them in front of their faces, which they took offense at. And then I went for a hike by myself. And my family thought I was eccentric for doing so.

In the fifteen years I’ve been trapped in Steubenville without a car, I have not been able to go for a hike more than a handful of times. I’d nearly forgotten how much my soul needs nature. I tried to make myself forget entirely because it was too much to bear. I was stranded in an irritating place, balancing a life I couldn’t stand, much as I’d been stuck in the bathroom with a porcelain basin balanced on one knee yelling for help. But now I have a car, and I’m a lot less trapped. I’m learning the highways and back roads. Yesterday Rosie wanted to stay home and watch Power Rangers on her tablet, but Michael promised to take over homeschooling. So I left, and I got the car out of its hiding place, and I went for a hike by myself.

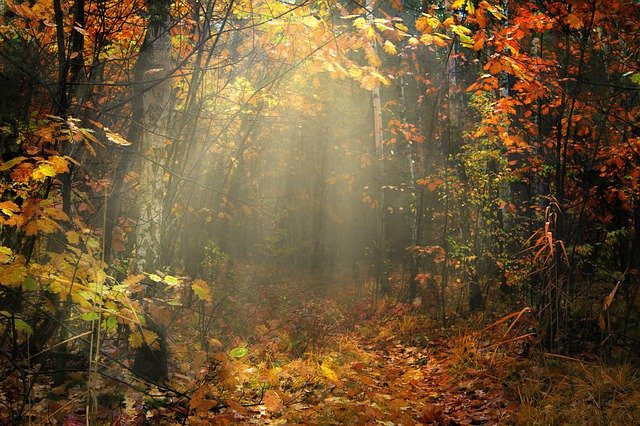

It’s the time of year that the color is at its apex. Everywhere you look, things are gold. The leaves are gold. The low sun on the storm clouds is gold. The muddy rushing downhill after an autumn storm are opaque golden brown with the sandy mud. The needles the pines have dropped all year are gold against the soil. Gold is the color of things that are going to sleep: the needles from pines that are going dormant for the year, leaves that are drying out and falling to the ground, the sun before it sets early on a late fall day, the water when it’s swollen with late fall rain and about to freeze over in the winter.

My grandfather used to go for hikes in weather like this. He hiked in all weather. He loved nature; he was an avid birdwatcher and a gardener. He knew the names of trees just from looking at the bark. I used to love going for walks with him, picking up random bits of plant matter from the ground and asking him to identify what they were. He always knew. And he was one of the only relatives who didn’t seem to hate me. He didn’t ignore me when I cried. He didn’t tease me for being ugly or eccentric. He just let me be near him.

Whenever I go for a hike, I always have the eerie feeling that my grandfather isn’t dead. I’ll turn the corner and see him, standing under a tree in his brown jacket, staring up through binoculars at something or other, ready to pass me the binoculars and tell me what it is. I’ll tell him that I can’t see through binoculars because my eyes don’t focus properly. I’ll squint at whatever it is and try to appreciate it, because I love him. And we will have a good time together, just like we did when I was young.

Every time I came around a bend my grandfather wasn’t there, so I told myself what everything was. This is a hemlock tree. This is a pine. This is a sycamore. That’s a cardinal, the father is bright red but the mother is brown. Cardinals don’t migrate. They will be here all year. Do you hear that noise? That’s just a crow.

I was sad. I missed him. I missed everyone I’ve lost in my strange, lonely, unremarkable life. But as I walked I became less and less sad.

I hiked over streams, getting my shoes soaked now and then. Then the path turned sharply uphill; it was dryer, and there were more pines to muffle my footsteps. I wasn’t sad or happy, but only quiet.

Then I got to the waterfall, and I snapped a few pictures and took some short video with my phone. And somehow I wasn’t sad anymore.

Nature always has that effect on me: first I am sad, and then I am quiet, and then I’m not sad anymore.

Even the walls of that waterfall were streaked with gold, as if they, too, were falling asleep.

All of nature is falling asleep right now, but it will wake up again.

I came to the Valley fifteen years ago, but one day I will leave. One day I will not feel like I’m trapped back in that cabin, balancing a broken sink on one knee and yelling at nobody for help. One day I’ll walk away for good, and not return to the Ohio Valley.

My grandfather fell asleep in the Lord six years ago, but one day the Lord will raise him. I will see him again, and we will go for a hike.

I drove home in the warm light of a late Autumn sunset, and for a moment, everything felt alive.

Image via Pixabay

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross and Stumbling into Grace: How We Meet God in Tiny Works of Mercy.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.