I threw a wood block at a child the other day. I had to. He was trying to break in my window and he didn’t run when I screamed. I went downtown and ratted him out to the police this afternoon. I had to. I didn’t want to. But I can’t just talk to his parents because they’re drunks, and they’re on drugs. They don’t even let him in the house during the day. He bikes around the neighborhood from early in the morning until night. I went downtown to the child services office, and they told me I had to tell the police. The police took my statement, and I tried not to look afraid.

Do you renounce Satan? I do.

Before I caught a bus home from the police station, I took my books back to the downtown library. It’s an historic building, one of those small but stately old Carnegie libraries with a funny mural inside, above the front door. The mural displays a map of the earth seen from the North Pole, a globe flayed and laid out flat with its pole in the middle. All the continents look so funny, upside down and sideways. You’d think you were looking at a foreign planet. Most of the earth looks like a foreign planet, when you live in the Ohio Valley.

At the library, the librarians were calling someone, maybe the police or the child services office where I’d just been, because an eight-year-old boy had walked to story time without a parent, through the worst part of town, holding the hand of his toddler brother. No one knew where his mother was. The little boy didn’t seem to know or care; he only wanted to make sure he didn’t miss next week’s story time. The librarian was trying to assure him that he would miss nothing. I wasn’t surprised. Child neglect is rampant in this area. I was happy the child had made his way to the library instead of getting lost in the slums.

Do you renounce Satan so as to live in the freedom of the children of God? I do. But he still lives here, you know.

As I waited for the bus, a train came by the intersection, one of the fracking trains. Fracking is the new industry that they said would save us from our poverty by creating jobs. And it did create jobs, and people from Texas and Tennessee who actually know how to frack came up with their pickup trucks to live in Steubenville and take the jobs. The price of rent went up, and we Ohio Valley People have stayed poor and out of luck. When the fracking industry inevitably implodes and the workers go back to Tennessee and Texas, we Ohio Valley people will remain here, poor and out of luck, just as we did with the steel industry, and the coal industry before that. I think timber came before coal, and so on down to the first syllable of the Ohio Valley’s recorded time when the white settlers built a fort to keep squatters out of the land they’d just taken in violation of England’s treaty with the local Indian tribes. I believe the Manongahela people were here before the settlers came, and as far as I recall they’re the ones that displaced the Iriquois who were here sometime after the Hopewell and Adena.

The Adena had no written record; they only left burial mounds, filled with clay pipes. Myriad pipes shaped like animals, and one large pipe shaped like a man– the only human-shaped artifact in the whole burial mound, the only one of its kind on earth. You can see it in the museum up in Columbus. The museum also has dioramas of the historic American Indians that displaced the Adena, and a room in honor of the white settlers that built forts. It has a model of a factory from the industrial revolution, a factory that no doubt used Ohio Valley coal. It has a model of a street from the Great Depression, and a room in honor of the second World War, when Ohio Valley steel became huge business. Someday, the museum will have a display about fracking, and another display about whatever comes after fracking. There won’t be a museum display about us, ordinary poor people here in the Ohio Valley. There won’t be any record that rent prices went up, or that little boys walked to the library without their parents, or that fracking trains made the buses late.

Do you renounce Satan? And All his pomps and works? I do. But he still lives here, you know. His pomps and works works have been among us since we came to the valley. They’ve been in every detail, in the industrial exploitation that might have created jobs for us, in the fort that might have protected people instead of serving as a base to take the Indians’ land, in the trains and the factories and the muskets and the tomahawks and all the people buried in that mound. Maybe the settlers brought him here. Maybe the Manongahela did, maybe the Adena. Maybe he’s somewhere below the flayed skin of the earth, but he’s also here on the surface with us.

The train went by, loud as freight trains always are, screaming on the brakes and blowing the horn. Two engines, several flatbeds with big metal spools on top, several tanks full of God knows what. The shabbily dressed woman next to me recited numbers aloud– not counting the cars, but naming their serial numbers as they went by. She was faster to spot them than I was. “One zero zero seven two one. One zero zero seven two five. One zero zero seven two nine. One zero zero seven three one.” She went on like that for five minutes.

Do you renounce Satan? And all his pomps and works? And all his empty promises? Master, I do. But when You saw Satan fall like lightning from the sky, did you see where he fell? He fell here. He fell to earth. He fell to the valley of the shadow of death, and darkness covers the land.

“One zero zero seven two eight. One zero zero seven three six.” Finally, the train passed. The shabby woman got on the bus to Mingo. I caught the next one, up to my house. There was just enough time for dinner before I caught a ride back downtown, to the Adoration chapel, for my holy hour. The door was shut and locked, so I had to press the buzzer to be let in. There’s a sign by that door cautioning worshipers not to give money to beggars, but to call the police instead; there’s another sign cautioning not to let anyone in to see Jesus after a certain time, unless they’re on the sign-up list. I opened the Bible to that strange lamentation in Ezekiel, the one about the two young lions. The lioness raised two whelps to be strong lions, but then the people came with hooks and led the lions away to Egypt and Babylon. I think it’s the people we’re supposed to feel for, and not the lions, but I’m not sure anymore.

When I came back, the police had already come and gone from the little boy’s house. I’m still not sure if they took him away. The neighbors all wanted to know what had happened, but I didn’t know what to say.

My child, do you renounce Satan?

Lord, you know all things. You know that I renounce Satan.

Do you believe in the Son of Man?

I do believe, Lord, and I worship You. What would you have me do?

Remain faithful, until I return.

Lord, when are you coming back?

Behold, I am coming soon.

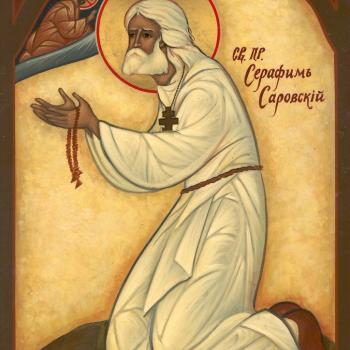

(image via Pixabay)