The emblematic importance of the Akedah, the binding of Isaac, for Latter-day Saints is certified by these words of Jacob:

Jacob 4:5 …we keep the law of Moses, it pointing our souls to him; and for this cause it is sanctified unto us for righteousness, even as it was accounted unto Abraham in the wilderness to be obedient unto the commands of God in offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son.

Just what are we to learn from this “similitude” between the Akedah and the sacrifice that is somehow the ground of our redemption? Leon Kass, not a Christian but a great scholar both of Judaism and Greek political philosophy, draws this conclusion from the binding of Isaac:

“God does not finally require that men choose between the love of your own and godliness. Though it took a horrible episode to demonstrate this fact, harmonization is possible between a reverence for God (who loves righteousness) and the love of one’s family or nation, rightly understood. God, the awesome and transcendent power, wants not the transcendence of life but rather its sanctification-in all the mundane activities and relations of everyday life. Thus, God displays Himself to be exactly the sort of god whom one could not only fear-and-revere, but even come to love-“with all thy heart, with all thy soul, and with all thy might” (The Beginning of Wisdom – article version available here. http://www.firstthings.com/article/1994/12/educating-father-abrahamthe-meaning-of-fatherhood

This seems to mean that the blessings Abraham received following the test of his willingness to sacrifice everything were exactly the blessings he was willing to give up – but “sanctified” – I would say “redeemed” by sacrifice. I think this is what is shown negatively by the great French film (based on a Marcel Pagnol novel and earlier film), tragedy of “Manon of the Spring [Source]. ” I won’t try to summarize the film, but for those of you who know it or might be persuaded to see it (start with its first part, “Jean de Florette”), here is the connection I see with the central teaching of Christianity on sacrifice and redemption: Papi had his fondest dreams of family and posterity within his reach; the greatest been given to him, right before his eyes, but he no faith to sacrifice his greed and receive it by opening his heart to others – he insisted on grasping his dreams by hard-hearted deceit, and ended up destroying them.

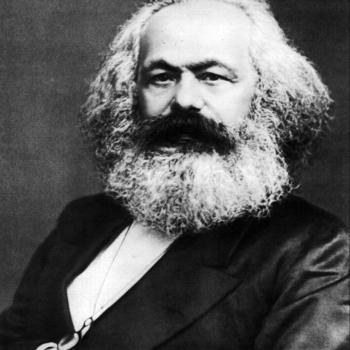

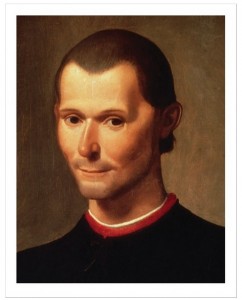

The tragedy is that Papi in the Pagnol film wants the blessings of eternal family, but he follows the philosophy of Korihor, which makes us radically alone (like Machiavelli’s project of winning this world by setting aside sacred restraints on human acquisition):

What does it mean to feel alone? When do we feel most alone? When you believe the world is as Korihor described it – when he denied the Atonement.

Alma 30:

16 Ye look forward and say that ye see a remission of your sins. But behold, it is the effect of a afrenzied mind; and this derangement of your minds comes because of the traditions of your fathers, which lead you away into a belief of things which are not so.

17 And many more such things did he say unto them, telling them that there could be no atonement made for the sins of men, but every man afared in this life according to the management of the creature; therefore every man prospered according to his genius, and that every man conquered according to his strength; and bwhatsoever a man did was cno crime.

18 And thus he did preach unto them, leading away the hearts of many, causing them to lift up their heads in their wickedness, yea, leading away many women, and also men, to commit whoredoms—telling them that when a man was dead, that was the end thereof.

It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to say that, despite the obvious good in much that is “modern,” the basic thrust of modern world, the “tectonic plates” above which we drift, are based upon this philosophy of Korihor-Machiavelli: we are left alone to use our own power and deceit, because the universe gives no support to love and responsibility for each other. Knowledge is power, whether deployed for the individual or on behalf of some collectivity. Or for a “humanity” unsupported and unrestrained by any source of meaning or order above human beings. So the point is not to understand the world, but to change it. (And to what end? Now there’s the question that must always be deferred. Call it “Progress.”)

But back to the good news: The whole point of the Atonement is to disprove this, or perhaps indeed to confirm the very nature of reality as based not on the loneliness of power but on sacrificial love.

One of the boldest and most searching reflections on the Atonement I know was offered by Elder Jeffrey R. Holland: “And None Were With Him” (April 2009) I quote at length:

Thus, of divine necessity, the supporting circle around Jesus gets smaller and smaller and smaller, giving significance to Matthew’s words: “All the disciples [left] him, and fled.” 15 Peter stayed near enough to be recognized and confronted. John stood at the foot of the cross with Jesus’s mother. Especially and always the blessed women in the Savior’s life stayed as close to Him as they could. But essentially His lonely journey back to His Father continued without comfort or companionship.

Now I speak very carefully, even reverently, of what may have been the most difficult moment in all of this solitary journey to Atonement. I speak of those final moments for which Jesus must have been prepared intellectually and physically but which He may not have fully anticipated emotionally and spiritually—that concluding descent into the paralyzing despair of divine withdrawal when He cries in ultimate loneliness, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” 16

The loss of mortal support He had anticipated, but apparently He had not comprehended this. Had He not said to His disciples, “Behold, the hour … is now come, that ye shall be scattered, every man to his own, and shall leave me alone: and yet I am not alone, because the Father is with me” and “The Father hath not left me alone; for I do always those things that please him”? 17

With all the conviction of my soul I testify that He did please His Father perfectly and that a perfect Father did not forsake His Son in that hour. Indeed, it is my personal belief that in all of Christ’s mortal ministry the Father may never have been closer to His Son than in these agonizing final moments of suffering. Nevertheless, that the supreme sacrifice of His Son might be as complete as it was voluntary and solitary, the Father briefly withdrew from Jesus the comfort of His Spirit, the support of His personal presence. It was required, indeed it was central to the significance of the Atonement, that this perfect Son who had never spoken ill nor done wrong nor touched an unclean thing had to know how the rest of humankind—us, all of us—would feel when we did commit such sins. For His Atonement to be infinite and eternal, He had to feel what it was like to die not only physically but spiritually, to sense what it was like to have the divine Spirit withdraw, leaving one feeling totally, abjectly, hopelessly alone.

But Jesus held on. He pressed on. The goodness in Him allowed faith to triumph even in a state of complete anguish. The trust He lived by told Him in spite of His feelings that divine compassion is never absent, that God is always faithful, that He never flees nor fails us. When the uttermost farthing had then been paid, when Christ’s determination to be faithful was as obvious as it was utterly invincible, finally and mercifully, it was “finished.” 18 Against all odds and with none to help or uphold Him, Jesus of Nazareth, the living Son of the living God, restored physical life where death had held sway and brought joyful, spiritual redemption out of sin, hellish darkness, and despair. With faith in the God He knew was there, He could say in triumph, “Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.” 19

Brothers and sisters, one of the great consolations of this Easter season is that because Jesus walked such a long, lonely path utterly alone, we do not have to do so. His solitary journey brought great company for our little version of that path—the merciful care of our Father in Heaven, the unfailing companionship of this Beloved Son, the consummate gift of the Holy Ghost, angels in heaven, family members on both sides of the veil, prophets and apostles, teachers, leaders, friends. All of these and more have been given as companions for our mortal journey because of the Atonement of Jesus Christ and the Restoration of His gospel. Trumpeted from the summit of Calvary is the truth that we will never be left alone nor unaided, even if sometimes we may feel that we are. Truly the Redeemer of us all said: “I will not leave you comfortless: [My Father and] I will come to you [and abide with you].” 20

…………………………………….

Christ overcame death and sin. At the very moment he was most alone, he proved that we are never alone – that there is more to life than every man conquering according to his strength.

Christ’s redeeming sacrifice shows us that we are never alone, and that our merely human love, our love for those near and dear, a love, that, through Christ overflows to embrace all God’s children – that this love will never fail.

This is the love that sanctifies “all the mundane relations and activities of everyday life.”

Now, politics in the full sense – the human responsibility for order in the city and in the soul – would seem to be among such “mundane relations and activities,” if not in some way paramount among them. So just what it would mean to exercise this responsibility (as a citizen or, in the event, as a statesmen) is … well, a very good question – perhaps even the question the lies at the intersection of charity and wisdom.