Welcome readers! Please subscribe through the buttons on the right if you enjoy this post.

In both Matthew’s and Luke’s gospels we read similar words:

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? Can anyone of you by worrying add a single hour to your life? And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith? So do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the pagans run after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them. But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.” (Matthew 6:25-33 cf. Luke 12:22-31)

I believe we can best understand these passages by looking at an interesting detail in Luke’s version of this saying. At the very beginning of this discourse in Luke, we read:

“Someone in the crowd said to him, ‘Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.’ Jesus replied, ‘Man, who appointed me a judge or an arbiter between you?’” (Luke 12:13,14)

In Jesus’ audience, a man is arguing with his brother over their inheritance from their father. One brother asks for Jesus to speak to the other brother on his behalf and Jesus flatly refuses to arbitrate between them.

Arguments over inheritances aren’t common among the poor or lower-middle classes. These are problems that exist among the affluent. My own mother passed away in 2014, a typical Appalachian woman with nothing. I remember having to sort through mail and having to speak with creditors. There was no inheritance to try and figure out; there was only debt to be cleared or written off.

Jesus didn’t see settling disputes between the rich as his purpose. He was a prophet of the poor and called his audience to solidarity with the poor. One example of this is Jesus call’ for the rich to “sell everything you have and give it to the poor.” It was a call for radical wealth redistribution.

It’s possible that those who heard Jesus teach believed that there would not be enough for everyone if we actually did share. This is a narrative of scarcity. It leads people to feel anxious about the future and preoccupied with accumulating as much as they think will insulate them from any negative future events. Accumulating resources and anxiety can grow into the drive to monopolize resources, exploit others and their resources, and uphold this exploitation through violence. However we label this narrative, we must learn to recognize it for what it is: a narrative of scarcity.

Jesus, on the contrary, taught a different narrative, a narrative more like the one Gandhi later taught, that “every day the earth produces enough for each person’s need, but not each person’s greed.” Jesus called us to embrace a narrative of enough or abundance, the belief that there is enough to share. This sharing replaces anxiety with gratitude, generosity, connectedness, community, and hospitality. Rather than monopolies and exploitation, abundance brings distributive justice and replaces violence with peace.

Let’s look at this passage again with these two narratives in mind:

“Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you are to eat, nor about your body, with what you are to clothe yourself. Is not life more than food, and the body than clothing? Consider the ravens: They neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet God feeds them. Are you not better than the birds? And who of you by being anxious is able to add to one’s stature a cubit? And why are you anxious about clothing Observe‚ the lilies, how they grow: They do not work nor do they spin. Yet I tell you: Not even Solomon in all his glory was arrayed like one of these. But if in the field the grass, there today and tomorrow thrown into the oven, God clothes thus, will he not much more clothe you, persons of petty faith! So‚ do not be anxious, saying: What are we to eat? Or: What are we to drink? Or: What are we to wear? For all these the Gentiles seek; for your Father knows that you need them all. But seek his kingdom, and all these shall be granted to you.”

Jesus’ “Kingdom,” the “reign of God,” was the gospel authors’ way of using the language of his own time and culture to share Jesus’ social vision of people taking care of each other. James M. Robinson reminds us in The Gospel of Jesus, “This is why the beggars, the hungry, the depressed are fortunate: God, that is, those in whom God rules, those who hearken to God, will care for them. The needy are called upon to trust that God’s reigning is there for them (“Theirs is the kingdom of God”) . . . Jesus’ message was simple, for he wanted to cut straight through to the point: trust God to look out for you by providing people who will care for you, and listen to him when he calls on you to provide for them.”

This is what Pëtr Kropotkin called mutual aid:

“While [Darwin] was chiefly using the term [survival of the fittest] in its narrow sense for his own special purpose, he warned his followers against committing the error (which he seems once to have committed himself) of overrating its narrow meaning. In The Descent of Man, he gave some powerful pages to illustrate its proper, wide sense. He pointed out how, in numberless animal societies, the struggle between separate individuals for the means of existence disappears, how struggle is replaced by co-operation, and how that substitution results in the development of intellectual and moral faculties which secure to the species the best conditions for survival. He intimated that in such cases the fittest are not the physically strongest, nor the cunningest, but those who learn to combine so as mutually to support each other, strong and weak alike, for the welfare of the community. ‘Those communities,’ he wrote, ‘which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members would flourish best, and rear the greatest number of offspring’ (2nd edit., p. 163). The term, which originated from the narrow Malthusian conception of competition between each and all, thus lost its narrowness in the mind of one who knew Nature.” (Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution)

In the New Testament book of James, the writer comments on Jesus’ teachings in the sermon on the mount and the narrative of anxiety that leads to exploiting others: “But you have dishonored the poor. Is it not the rich who are exploiting you? Are they not the ones who are dragging you into court? Are they not the ones who are blaspheming the noble name of him to whom you belong?” (James 2:6-7)

As the gospels do, James gives a scathing, prophetic pronouncement to those who live by the old narrative of scarcity and accumulation:

“Believers in humble circumstances ought to take pride in their high position. But the rich should take pride in their humiliation—since they will pass away like a wildflower. For the sun rises with scorching heat and withers the plant; its blossom falls and its beauty is destroyed. In the same way, the rich will fade away even while they go about their business.” (James 1:9-11)

Even in 1 Timothy, believed to have been written quite a bit later than James, there is a call away from the narrative of scarcity, anxiety, and individualistic trust in one’s own accumulated wealth to insulate one from future harm:

“Command those who are rich in this present world not to be arrogant nor to put their trust in wealth, which is so uncertain, but to put their hope in God, who richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment.” (1 Timothy 6:17)

Remember, putting one’s “hope in God” in the gospels meant trusting God enough that God would send people to take care of you as you share what you’ve accumulated with those God calls you to give to today.

“Ravens and lilies do not seem to focus their attention on satisfying their own needs in order to survive, and yet God sees to it that they prosper. Sparrows are sold a dime a dozen and, one might say, who cares? God cares! Even about the tiniest things—he knows exactly how many hairs are on your head! So God will not give a stone when asked for bread or a snake when asked for fish, but can be counted on to give what you really need. You can trust him to know what you need even before you ask. This utopian vision of a caring God was the core of what Jesus had to say and what he himself put into practice. It was both good news—reassurance that in your actual experience good would happen to mitigate your plight—and the call upon you to do that same good toward others in actual practice. This radical trust in and responsiveness to God is what makes society function as God’s society. This was, for Jesus, what faith and discipleship were all about. As a result, nothing else had a right to claim any functional relationship to him . . . [Jesus] sought to focus attention on trusting God for today’s ration of life, and on hearing God’s call to give now a better life to neighbors . . . All this is as far from today’s Christianity as it was from the Judaism of Jesus’ day. Christians all too often simply venerate the “Lord Jesus Christ” as the “Son of God” and let it go at that. But Jesus himself made no claim to lofty titles or even to divinity. Indeed, to him, a devout Jew, claiming to be God would have seemed blasphemous! He claimed “only” that God spoke and acted through him.” (James Robinson, The Gospel of Jesus, Kindle Location 102)

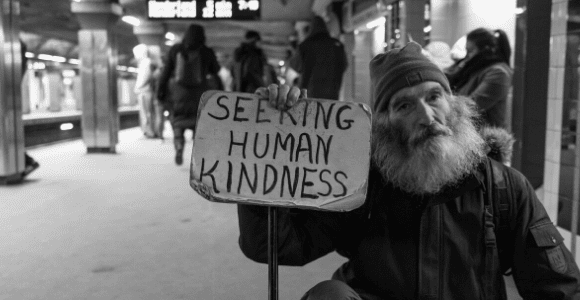

This is the vision Jesus cast before his listeners of what human society could look like: People taking care of people. In Jesus’ theological language, that was God taking care of people through people. It’s through us, through our choice to be compassionate and just or turn away, that we determine one another’s fate. We have a choice to make. Will we care for someone today, trusting that someone will care for us tomorrow if we have a need?

“Seeking first the Kingdom” is not seeking an artificial quid pro quo where if I help people, I expect God to supernaturally bless me. This isn’t the prosperity gospel. This is more intrinsic. As I take care of others when they need care, I’m setting in motion a world where I’ll have folks that take care of me if I need care. Like we discussed last week, I’m investing in people today. And that will intrinsically create a reality where others will share “all these things” with me if I experience a crisis.

Jesus’ teaching means the creation of a human society in which we change the nature of the world we live in, where care and cooperation solve the dilemmas of survival rather than competition, domination, subjugation, and exploitation. This world is not based on a win-lose closed system, but a win-win where we learn to be each other’s keeper. Our world is what we, collectively, choose to make it. For my part, I’m choosing compassion.