I have an unusually long commute these days, a burden I am taking steps to alleviate. The commute is redeemed somewhat by the opportunity to listen to audiobooks. If someone sets out to be a writer, the first piece of advice they get to is to keep writing. The second is to keep reading. I would append the second bit of advice to say “Keep reading. When possible, read out loud or be read to.” There is something special about the way hearing a book, story, or poem read aloud can tune a writer’s ear to the music of language and good storytelling.

For the most part, I’ve been using the commute as an opportunity to reread books. Last month I listened to four of Hemingway’s classic books – A Moveable Feast, The Sun also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, and The Old Man and the Sea – read by the likes of William Hurt, Donald Sutherland, and John Slattery. I’m also rereading Wendell Berry’s Port William fiction, comprised of nine novels and dozens of short stories. Berry’s collected stories, That Distant Land, includes a chronological arrangement of all his fiction. I’m using that arrangement as a guide, beginning with “The Hurt Man,” set in 1888, and concluding with Hannah Coulter (2001). I’ve gotten as far as Andy Catlett: Early Travels (1943). I expect to read through Berry’s collected fictions twice this year, in preparation for a long essay I want to write in the fall.

My favorite Wendell Berry novels are The Memory of Old Jack (1952) and Jayber Crow (1986), both of which were featured in 2009 in an issue of Oxford American magazine celebrating great Southern fiction. Now that I am about a quarter of the way through my first chronological exploration of the Port William fiction, I thought I would post here the short essay I wrote about Jayber Crow for my book, Besides the Bible: 100 Books that Have, Should, or Will Create Christian Culture. (Besides the Bible, co-written with Dan Gibson and Jordan Green, was recently republished by InterVarsity Press.) Berry’s work in general – and Jayber Crow in particular – planted some of the earliest seeds of Slow Church. I’m guessing many of our Slow Church friends are familiar with Wendell Berry’s writing. If so, have you found your way to his fiction yet? Do you have a favorite novel?

Here is that essay:

“I will have to share the fate of this place.

Whatever happens to Port William happens to me.”

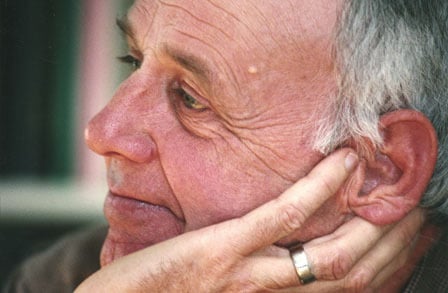

As a novelist, essayist, poet, and farmer, Wendell Berry has plowed the same plot of Kentucky hillside for nearly fifty years. His focus across all literary forms is healthy community built on fidelity to neighbor, creation, and creator.

The principles Berry argues for in his essays with the rigorous logic of a legal brief are tenderly brought to life in his novels and short stories, which are all set in and around the fictional village of Port William, Kentucky. The title character in Jayber Crow is not native to Port William. Jayber’s parents died when he was only three. Aging relatives in Squires Landing, a few miles from Port William, take him in, but several years later they die too. “I was a little past ten years old,” he says, “and I was the survivor already of two stories completely ended.” He is sent to an orphanage in central Kentucky, and doesn’t return to the area until he drops out of college and goes looking for “a loved life to live.”

When Jayber arrives in Port William, the town needs a barber, a job he happens to know how to do. He spends the next fifty years cutting hair, gradually being drawn into the life of the community. He falls in love with a girl who marries a man unworthy of her, and for decades he loves her from afar. Jayber performs several essential services for Port William. Besides cutting hair, Jayber’s barbershop becomes a meeting place. Whether they need a trim or not, men are always stopping by to share the latest news, catch up, or just watch life happen on the street outside the shop window. The old men tell him stories, and Jayber becomes a guardian of the town’s communal memories.

Berry repeatedly describes the people of Port William as a “membership,” an image derived from Paul’s letters to the Ephesians and Corinthians. Burley Coulter, a recurring character in Berry’s fiction, says in one short story, “The way we are, we are members of each other. All of us. Everything. The difference ain’t in who is a member and who is not, but in who knows it and who don’t.” Jayber becomes a part of this membership, and he sees in it a reflection of the gathered Church:

It was a community always disappointed in itself, disappointing its members, always trying to contain its divisions and gentle its meanness, always failing and yet always preserving a sort of will toward goodwill…And yet I saw them all as somehow perfected, beyond time, by one another’s love, compassion, and forgiveness, as it is said we may be perfected by grace.

And so there we all were on a little wave of time lifting up to eternity, and none of us ever in time would know what to make of it. How could we? It is a mystery, for we are eternal beings living in time.

The poem, novel, essay, and small farm were all pronounced dead by the experts long ago, but Berry’s voice is more vital than ever. The values Berry has been advocating for years – especially localism and settledness – are gaining broader popularity, thanks in part to mainstream writers like Michael Pollan and Bill McKibben who look to Berry as a mentor. (“To feel at home in a place, you have to have some prospect of staying there,” Jayber says.) It is a quiet movement, manifesting itself in the growing presence of farmers’ markets in communities large and small, urban and guerilla gardens, in the lives of people moving back to the country to work the land, and in the lives of people who apply the standards of health and good use to their work as teachers, lawyers, homemakers, and barbers. It is a return to story and to belonging, and for five decades the voice crying out in the wilderness has been that of Wendell Berry.