Evangelicals are “born-again” Christians. We are converts. Even those of us who were raised from birth within evangelical churches, evangelical families, and evangelical culture.

It may seem strange to describe the recitation of a prayer by a grade-school child in a Sunday school class they cannot remember ever not attending as a “conversion,” but that is how we tell our stories as evangelicals — our “personal testimonies” recounting and affirming our moments of conversion and salvation.

It may seem strange to describe the recitation of a prayer by a grade-school child in a Sunday school class they cannot remember ever not attending as a “conversion,” but that is how we tell our stories as evangelicals — our “personal testimonies” recounting and affirming our moments of conversion and salvation.

Evangelicals are converts and we are conversionist. We believe in and promote evangelism. Evangelicalism is a missionary form of religion, one that sees the seeking and making of converts as both a duty and an expression of love. We have been saved and now we want others to be saved as well.

When I worked for a group called “Evangelicals for Social Action” in the 1990s, I spent a lot of time having to explain the distinction between “evangelical” and “evangelist” or between “evangelicalism” and “evangelism.” The words are obviously closely related and, for those unused to them, confusingly similar. An evangel-ical refers to a born-again Christian — a convert who is part of the stream of Christianity marked by its emphasis conversion and evangel-ism. An evangel-ist refers to a person whose profession or calling is the preaching of the gospel and the seeking of converts. Those converts will become evangel-icals.

Billy Graham was both an evangel-ical and an evangel-ist. Most evangelists are evangelicals. And most evangel-icals believe that they are also supposed to be evangel-ists. (At the very east they believe that they have a duty to invite their “unsaved” friends to come with them to listen to the more gifted evangelists among us.)

The two terms are easily confused because they are overlapping and intrinsically connected. Evangelical Christianity is essentially evangelistic.

That is the point here. There are many necessary and important conversations that could and should also follow this point — conversations about what constitutes good or bad evangelism, loving or unloving proselytizing, effective or ineffective persuasion, explicit or implicit witness, etc. That’s all vital and fascinating, but not the point here.

Here I simply want to emphasize the obvious and uncontroversial starting point: Evangelical Christianity is evangelistic. Evangelism is at the core of evangelicalism. Evangelical Christianity is the product of evangelism. Evangelism is a key practice of evangelicalism. You can’t have one without the other.

I don’t think any of my fellow American white evangelicals would disagree with that. I am not accustomed to seeking or receiving “Amens” from the likes of Al Mohler or Lance Wallnau or Franklin Graham, but I’d get one from them here when I say, again, that evangelism is at the essential core of evangelical practice and identity. They say this themselves. We don’t agree on much, yet we agree on this.

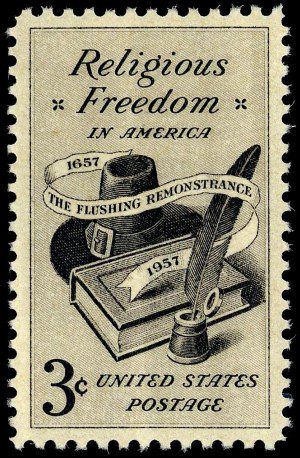

But here’s where I’ll lose them. Because here is where I want to return to 1657 and the Flushing Remonstrance.

You could not be an evangelist in Peter Stuyvesant’s New Amsterdam. You were not allowed to evangelize and you were not allowed to listen to evangelists.

That situation was not unique to Stuyvesant’s colony. It was also true in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (again, just ask Ann Hutchinson or Roger Williams). And it was true in England under Henry or Mary or Cromwell or Charles.

The centuries of intolerable religious turmoil we discussed in the previous post about the Flushing Remonstrance were the product of established Christianity. It didn’t matter which flavor of established Christianity prevailed at any given moment — Puritanism or Catholicism or Anglicanism. None of them permitted the possibility of evangelism. It was almost impossible under established Christianity for anyone to hear or to be an evangelist. Conversion was not a legal option. Options were not a legal option.

And without options — without the possibility of conversion, of switching churches or choosing churches — there can be no such thing as either evangelism or evangelicalism.

Which is to say that nothing like evangelical Christianity could exist or did exist at any significant scale until after the rise of the kind of pluralistic liberal democracy heralded by the Flushing Remonstrance.*

Evangelical Christianity could not exist in anything like its present form in the context of established religion. Established religion precludes and prohibits evangelism. Established religion precludes and prohibits evangelicalism. Established evangelicalism is an oxymoron.

And yet today, in 2024, the vast majority of white evangelicals in America are establishmentarian. They seem to hate the First Amendment even more than frightened schoolchildren hate the Second.

Evangelicals are enthusiastic supporters of politicians who promote the state-establishment of religion. If you hear someone in America railing against the separation of church and state, that person is almost certainly a white evangelical. (Or else they’re a white Opus Dei Catholic empowered and enrobed by white evangelicals who foolishly regard Catholic integralists as their allies.)

In 2024, in America, the vast majority of white evangelicals want to do away with the very same liberal pluralism that makes evangelism and evangelicalism possible. They are cheerfully sawing off the branch on which they are sitting. They are planting dynamite under the foundations of their own churches and ministries.

I don’t think they’ve thought this through.

* Probably the most useful popular attempt to describe “evangelicalism” is the Bebbington Quadrilateral, which rightly includes “conversionism” as one of its four key components. That comes from David Bebbington’s book Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History From the 1730s to the 1980s.

This history of evangelicalism could not start before about the 1730s because “conversionism” was simply not a possibility before then. It was an illegal, unimaginable non-thing. In the world of government-established Christianity, there were no evangelists and no evangelicals. Those things could not come to be or to flourish until liberal toleration and liberal pluralism allowed them to exist.