Last year, Richard Beck started blogging his way through the Psalms, one per week, offering his reactions and reflections. Here’s the first entry, “Psalm 1,” from last June. Beck has faithfully stuck with this plan, making his way through more than a third of the book so far.

That’s why this weekend, the first words you’d read on Beck’s lovely, gentle blog were these, from Friday’s post: “They will bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked.”

That’s why this weekend, the first words you’d read on Beck’s lovely, gentle blog were these, from Friday’s post: “They will bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked.”

The timing was a bit too timely, but that’s the Psalms for you, and that’s what it says right there in Psalm 58:

The wicked will be swept away.

The righteous will be glad when they are avenged,

when they dip their feet in the blood of the wicked.

Then people will say,

“Surely the righteous still are rewarded;

surely there is a God who judges the earth.”

This isn’t the first of the “imprecatory Psalms” that Beck has written about in this series. These are the Psalms of “vengeance and cursing” that so perturbed C.S. Lewis that he wound up writing a whole book about them.

Here in Psalm 58, the cursing and longing for vengeance are directed against unjust rulers who do not “judge with equity,” who “devise injustice,” and who “mete out violence on the earth.”

Those guys, man. I hate those guys too.

I’m totally down with seeing them “vanish like water that flows away.” I share the psalmist’s hope/wish/prayer that their arrows will fall short every time they draw their bow. I’d stop somewhere short of dreaming about dipping my feet in their blood, but otherwise, yes, if there is any “God who judges the earth,” and if that God is at all worthy of worship or respect, than I agree with the psalmist that such a God had better get busy with the sweeping away of such wicked, unjust, powers that be.

As this Psalm — and dozens of others — argues, God isn’t doing the name of God any favors by letting the unjust prosper. God’s reputation is at stake here. Centuries later, in Galatians, Paul asserts that “God is not mocked, for whatever a man sows, that will he also reap.” That’s the flip-side of the argument made throughout the Psalms, which points out that God is mocked whenever unjust, violent Powers That Be escape without reaping what they have sown.

It seems to me that the psalmists have a compelling point. Alas, though, it doesn’t seem like God finds this argument convincing, based on, for example, most of human history.*

Richard Beck suggests that Psalm 58 provides a different way of understanding the imprecatory Psalms with their bloodthirsty calls for vengeance, a way that allows us to read such prayers without contradicting “the One who said ‘Love your enemies’.”

The key here, he suggests, is in that first verse. In the New International Version, Psalm 58:1 is translated this way: “Do you rulers indeed speak justly? Do you judge people with equity?”

But in the New Revised Standard Version, and in some other English translations, the verse says: “Do you indeed decree what is right, you gods? Do you judge people fairly?”

Following the latter, in which “the oppressors named at the start of the Psalm are not human beings, they are gods,” Beck writes:

Here, as in other places in the Psalms, we encounter the strange cosmology and angelology of the Bible. The source of violence and oppression on the earth is due to divine archons who “rule” and “steward” the nations. These are the “principalities and powers” of the New Testament. Satan is the chief of these dark powers, the “god of this world” and the “prince of the power of the air.”

Given this cosmology, we can legitimately read Psalm 58 as being directed at these spiritual archons, and Satan principally so. In fact, I would confidently argue that this is exactly how Jesus read these Psalms. Throughout the gospels Jesus directs violence and hatred away from human beings to focus it upon his battle with the devil. This is one of the big points I make in Reviving Old Scratch, how when we moderns dismiss the devil from our spiritual and moral considerations our violence has nowhere to go but toward other human beings. Without the demons we will demonize each other. By shifting our vengeance away from “flesh and blood” toward the “principalities and powers in the heavenly realm” dark human emotions can be safely redirected and deflected away from human persons.

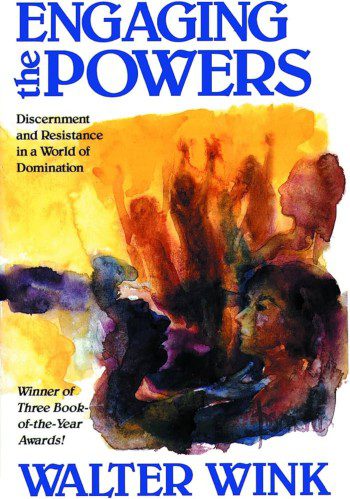

The turn here is toward Walter Wink’s theology of “the powers.” That’s rich, deep, fertile stuff and Richard Beck has both read and understood far more of Wink’s theology than I have. (For an excellent intro to Walter Wink, scroll down the sidebar on Beck’s homepage to find the links to his series “On the Principalities and Powers.”)

If this talk of “archons” and “dark powers” seems too strange, think of a more familiar expression of this from the Gospels: “You cannot serve God and Mammon.” Mammon there is the personification of money or wealth as a god-like ruler.

One specific problem with this Wink-ian reading of Psalm 58 is that here, the “gods” bleed. These unjust gods or rulers are flesh-and-blood enough that the righteous will “bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked.”

These “gods” are also born, Psalm 58 tells us in verse 3: “Even from birth the wicked go astray; from the womb they are wayward, spreading lies.” Sure sounds like flesh and blood to me.

The “spiritual warfare” of Wink and Beck is a very, very different thing from the “spiritual warfare” of a Frank Peretti novel or from the nonsense promoted by the charisMAGA “prophets” of cable television and the internet. But the latter’s popularity undermines Beck’s case that “Without the demons we will demonize each other.” The people who most believe in literal demons are the people most likely to demonize other people. They’re doing it right now, on an industrial scale.

Old Scratch himself points this out in almost every story of the kind in which he’s ever referred to as “Old Scratch,” from Hawthorne to Pacino.

“I have a very general acquaintance here in New England,” Old Scratch tells Young Goodman Brown. “I helped your grandfather, the constable, when he lashed the Quaker woman so smartly through the streets of Salem; and it was I that brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village, in King Philip’s war.”

Whatever help the Devil may have provided, it was flesh-and-blood mortals who hanged Mary Dyer and flesh-and-blood humans who burned those villages and stuck King Philip’s head on that pike just down the road. And it was mortal humans who chose to enslave, sell, rape, and torture their fellow mortal humans by the millions, for centuries, without ever skipping church on Sundays.

Old Scratch seems redundant. We got this on our own.

None of that means we should dismiss the argument that Beck (and Wink) are making here. Injustice is always systemic, and focusing only on the individuals in thrall to those systems (willingly or unwittingly) can distract us from naming and dethroning the Powers That Be that shape, demand, incentivize, and reward their individual unjust actions. It is helpful and necessary to name those powers and to challenge them as such: Empire, capitalism, patriarchy, racism, fascism.

No one can serve two masters, if you love the one you’ll hate the other, etc.

That’s what makes Beck’s post accidentally timely. If you forget that our battle is not only against flesh and blood, but also “against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms,” then we might start to think that killing one fascist is a sufficient substitute for dethroning or exorcising fascism itself.

In any case, whether or not we think of the unjust rulers and gods and archons and systems and Powers That Be as “flesh and blood,” those they oppress, prey on, plunder, and steal from are undeniably so. And whether or not our prayers or actions on their behalf are as graphic as the imprecatory Psalms, we will also be forced to choose where and how to place our own flesh and blood in all of this. We can stand with and alongside the victims, or we can bow before the wanna-be gods who devise injustice and mete out violence on the earth.

No matter how abstract or metaphorical or spiritual a framework we devise for thinking about that choice, the choice itself will never be abstract.

* Beck’s response to this argument in the Psalms is probably the best available response, which is to say that justice is not illusion, but that it is, rather, eschatological:

We cry out for vengeance, but judgement is deferred and left to God. Oppressors and evildoers will face a reckoning, and the victims of history will be vindicated. But this is not our job. We pray Psalm 58 as an eschatological lament. We leave the judgment of history to God.

One famous variation of this eschatological hope is what the Unitarian abolitionist minister Theodore Parker said back in 1853: “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe, the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. But from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

This can be reduced to a “pie in the sky when you die” opiate for the masses and an excuse to abandon our own responsibility for bending the arc ourselves, here and now, with our flesh and blood and muscle and bone.

But the hope of eschatological justice does not preclude the urgent need and responsibility for present justice. See, people assume that justice is a strict progression of cause to effect, but actually, from a non-linear, non-subjective viewpoint, it’s more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey … stuff. (That got away from me, yeah.)