A heated argument among political scientists studying white rural voters has me thinking again of C.S. Lewis’ Reflections on the Psalms.

The common thread here is resentment. That’s a central theme in both of these discussions. And, I think, it’s a source of confusion for both as well, because both are focused mostly on resentment as something that people who have been wronged feel toward those who have done them wrong. And that ain’t what it is. Resentment mostly flows the other way. It is something that people who have done — or are doing — wrong to others feel toward those they are harming.

The political scientists arguing about what drives the defiantly self-defeating behavior of white rural voters are fighting over different interpretations of the causes and effects of those voters’ resentments. C.S. Lewis was compelled to wrestle with and write about the Psalms because he was unsettled by the imprecatory Psalms of wrath and cursing. His reflections on the legitimate resentments of the oppressed and how those can curdle into the sin of wrath closely parallel the political scientists’ argument, which centers on this same distinction between “resentment” and “rage.”

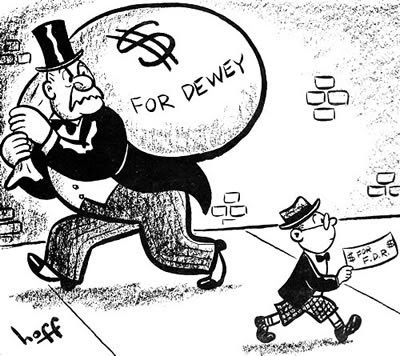

“Rage” is right there in the title of the new book from one faction in this poli-sci argument. Tom Schaller and Paul Waldman’s White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy was published in February. Nicholas F. Jacobs’ book, The Rural Voter: The Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America, (co-written with Daniel M. Shea) was published just a few months earlier. Jacobs’ book probably should’ve been called “The White Rural Voter,” and the fact that he didn’t call it that or fully realize that’s what it was about is also a big part of the argument here.

Jacobs fired the first shot in this niche academic turf war, writing a long polemical attack on the rival book for Politico: “What Liberals Get Wrong About ‘White Rural Rage’ — Almost Everything.” Schaller and Waldman responded, at length and in specifics, in The New Republic, “An Honest Assessment of Rural White Resentment Is Long Overdue.”

Both articles are personal and a little catty and both sides land some punches. Both are presented as explanations for why their book is the one that politicians seeking the support of white rural voters need to read while neither one actually offers much practical or substantive advice for any such politician. I do recommend both articles, though, to anyone compiling lists of contemporary euphemisms for racism. You’ll find plenty of those.

The best cut-to-the-chase summary of this argument I’ve seen comes from Tom Scocca: “A basket of nothing.” Scocca remains an enemy of and an antidote to smarm, and discussions of what motivates white Trump voters tend to be rich in smarm.

Here’s Scocca’s summary of the part of this argument that has me re-reading C.S. Lewis on the Psalms:

Accusing white rural Americans of being driven by rage, Jacobs wrote, will “marginalize and demonize a segment of the American population that already feels forgotten and dismissed by the experts and elites.” What Democrats and big-city liberals might want to call “rage,” he wrote, is correctly understood as “resentment — a collective grievance against experts, bureaucrats, intellectuals and the political party that seeks to empower them, Democrats.”

The key difference, Jacobs wrote, is that unlike rage, resentment “is rational, a reaction based on some sort of negative experience.”

That echoes Lewis’ efforts to parse a distinction between the legitimate, logical resentment of the oppressed and the disturbing “wrath” of Psalm 109 or Psalm 137 (“Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock!”).

This led Lewis to consider the double evil of oppression. To treat others unjustly, to “take from a man his freedom or his goods,” is the first sin. The second is the way this injustice tempts the oppressed person by arousing “resentment” that can become “vindictive hatred.” Lewis writes:

The natural result of cheating a man, or “keeping him down” or neglecting him, is to arouse resentment; that is, to impose upon him the temptation of becoming what the Psalmists were when they wrote the vindictive passages. He may succeed in resisting the temptation; or he may not. If he fails, if he dies spiritually because of his hatred for me, how do I, who provoked that hatred, stand? For in addition to the original injury I have done him a far worse one. I have introduced into his inner life, at best a new temptation, at worst a new besetting sin. If that sin utterly corrupts him, I have in a sense debauched or seduced him. I was the tempter.

This leads Lewis to consider the ways in which he and those like him — privileged white citizens of the British Empire — are guilty of such double-sins against multitudes of people around the world:

We had better look unflinchingly at the sort of work we have done; like puppies, we must have “our noses rubbed in it.” … We ought to read the psalms that curse the oppressor; read them with fear. Who knows what imprecations of the same sort have been uttered against ourselves? What prayers have Red men, and Black, and Brown and Yellow, sent up against us to their gods or sometimes to God Himself? All over the earth the White Man’s offense “smells to heaven”: massacres, broken treaties, theft, kidnappings, enslavement, deportation, floggings, lynchings, beatings-up, rape, insult, mockery, and odious hypocrisy make up that smell.

That passage made a splash on social media back in December where it was half-jokingly described as “Woke C.S. Lewis.” (I wrote about that here: “Merry Christmas from Woke C.S. Lewis“).

Yes, ha-ha, Lewis was “woke” in that he recognized injustice and oppression — “massacres, broken treaties, theft, kidnappings, enslavement, deportation, floggings, lynchings, beatings-up, rape, insult, mockery” — as moral depravity and abominable sins. “All over the earth the White Man’s offense smells to heaven” is exactly the kind of sentence that “anti-woke”* white evangelicals are trying to ensure that schoolchildren never read. So the jokes about how this passage from Lewis would seem to land in the context of our current culture wars** were funny and apt.

And Lewis was surely correct about the way in which the oppressor — Pharaoh, Caesar, “the White Man” — also becomes guilty of tempting the oppressed to succumb to the sins of despair, resentment, and wrath.

But — and here’s the point — I don’t think Lewis fully understands the dynamics of resentment. I think he misunderstands that in precisely the same way that Nicholas F. Jacobs seems to.

Because most resentment doesn’t punch up. Most resentment punches down. The rich resent the poor. The hegemonic majority resents the disenfranchised minority. The enslaved resents the enslaved. The abuser resents the abused. The usurer resents the debtor. The powerful resent the powerless.

Yes, of course, the “logical” form of resentment also exists. Exploited workers sometimes do resent the bosses exploiting them. But not always. And 100% of those predatory bosses resent those exploited workers.

One of my favorite descriptions of resentment is from Tolstoy: “I sit on a man’s back choking him and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am sorry for him and wish to lighten his load by all means possible … except by getting off his back.”

The poor fellow being choked and burdened here isn’t “utterly corrupted” by the “besetting sin” of resentment. He may have some thoughts about turning the tables, or someday receiving some reparation for what is unjustly being done to him. But mainly, overwhelmingly, his concern is simply getting this guy off his back.

Tolstoy’s first-person oppressor here, however, is utterly corrupted and wholly consumed by his resentment of the very man he is, present-tense, exploiting and choking. He has succumbed to the “spiritual death” that Lewis feared. The oppressor feels aggrieved because of his constant need to offer assurances to himself and others that he’s not a bad guy. That perpetual need to keep saying that, to himself and to others, to have to repeatedly assert “I’m not a bad guy, really I’m not!” is, for this man, “some sort of negative experience.” And thus it seems, to him, that resentment is, as Jacobs says, “rational, a reaction based on some sort of negative experience.”

Again, the “logical” form of resentment certainly also exists. The person who has been done wrong sometimes resents the person who has done them wrong. But that’s not what most resentment is. Most resentment works the other way around.

We resent those we have wronged. We resent those we have harmed. We resent those we are harming.

If it weren’t for them, after all, we wouldn’t have to spend so much time and energy reassuring ourselves and others that we’re still good people. If it weren’t for our annoying, bothersome victims, we’d be so much happier. If not for them, we wouldn’t have to worry about whether or not our offenses smelled to heaven.

And so we ask for mirth from those we torment, demanding that they “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

That is the most common, pervasive form of resentment. It may not seem as “rational” or “legitimate,” but it is very much, and almost always, “the natural result” of oppression and wrongdoing.

And that is the resentment that eludes those enmeshed in the poli-sci feud over white rural MAGA-fever, even as it preoccupies them.

Schaller and Waldman come closest to grasping this when, after acknowledging all of the legitimate reasons that white rural voters have for feeling exploited, neglected, or abandoned, they consider the non-white rural Americans who go mostly unmentioned in Jacobs’ book and seem invisible in his argument:

We would ask rural scholars to confront this question: How is it that rural minorities, who by most measures face even greater challenges in health care access and economic opportunity than their white counterparts, do not express weakened commitments to our democracy, or the anti-urban, xenophobic, conspiracist, and violence-justifying attitudes so many rural whites do? …

Those who have risen to defend the honor of rural whites insist that they have good reason to feel resentful … But if the rural experience justifies resentment, should not rural minorities be equally if not more resentful than rural whites? Why aren’t they threatening their local elected officials, or marinating in conspiracy theories, or supporting demagogues eager to tear down American democracy? Too few scholars of rural politics confront these questions.

That’s an important question that ought to lead to an even more important question, and then to some even more important answers. And those questions and answers are necessary not just for understanding the political science of rural America, but for understanding all of American history and religion.

* You already had “anti-woke” in that list of euphemisms for racism, right? OK, just checking.

** Should also be on that list.