“Rule No. 6: Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

— George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language“

For a good discussion of what I mean when I say that morality is story, not rules, here’s a post from late last year in which Richard Beck discusses David Bentley Hart’s essay “A Sense of Style: Beauty and the Christian Moral Life.” Beck’s post is titled “The Ethical as the Beautiful: Part 2, A Particular Manner of Conducting Oneself” because it’s one of several thoughtful posts on Hart’s essay.

Some of this may seem abstract — a discussion of the unity of the transcendentals in Christian metaphysics, meaning that the good and the beautiful and the true must all be the same. Well, yeah, fine, but we all also have to go to work and catch up on laundry and save our democracy and whatnot, so who has time for such ethereal pondering?

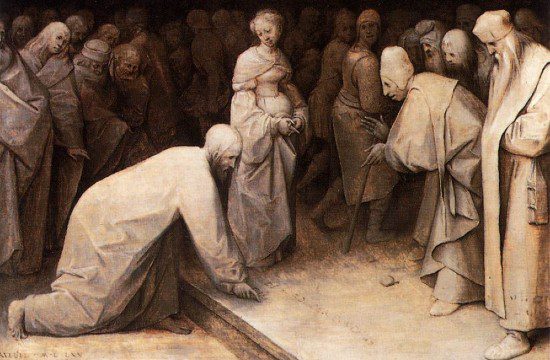

Don’t worry, though, Hart’s argument is actually eminently practical. Beck focuses on this section from Hart’s reflections on the story of the woman caught in adultery that got snuck into the eighth chapter of the Gospel of John. Here’s David Bentley Hart:

To see what I mean, consider for instance the story of the woman taken in adultery: it is a tale that in a sense refuses to leave us with any exact rule regarding any particular ethical situation, much less any single rule for all analogous situations; but it definitely provides us with a startlingly incisive exemplar of an extremely particular manner for conducting oneself, even in circumstances that might be fraught with moral ambiguity, or even with terror, and for negotiating those circumstances by way of pure bearing, pure balance. Christ’s every gesture in the tale is resplendent with any number of delicately calibrated and richly attractive qualities: calm reserve, authority, ironic detachment, but also tenderness, a kind of cavalier gallantry, moral generosity, graciousness, but then also alacrity of wit, even a kind of sober levity (“Let him among you who is without sin . . .”). All of it has about it the grand character of the effortless beau geste, a nonchalant display of the special privilege belonging to those blessed few who can insouciandy, confidently violate any given convention simply because they know how to do it with consummate and ineffably accomplished artistry— aplomb, finesse, panache (and a whole host of other qualities for which only French seems to possess a sufficiently precise vocabulary). And there is as well something exquisitely and generously antinomian about Christ’s actions here. It embodies the same distinctive personal idiom that is expressed in the more gloriously improbable, irresponsible, and expansive counsels of the Sermon on the Mount—that charter of God’s Kingdom as a preserve for flaneurs and truants, defiantly sparing no thought for the morrow and emulous only of the lilies of the fields in all their iridescent indolence.

One stylishly beautiful thing here is Hart’s positive use of the word “antinomian.” Beck expands on that, writing:

This is David Bentley Hart, so feel free to Google definitions. … An important word to track down for what Hart is saying is his descriptions of Jesus’ actions as “antinomian,” meaning “relating to the view that Christians are released by grace from the obligation of observing the moral law.”

If you’re unfamiliar with antinomianism you may want to explore that rabbit hole of Christian history, thought, and controversy. But at its heart Christian antinomianism simply follows St. Augustine’s famous line, “Love, and do what you will.” The idea being that, if we truly love others, we don’t need to follow any moral rules, code, or law. Love, on its own, will create a good moral outcome. As Paul famously wrote, “Love is the fulfillment of the law.”

The rabbit hole Beck mentions there is still in business. “Antinomianism” is still a go-to accusation weaponized by rules-obsessed, rules-confused Christians against anyone they see as a threat. As a general rule, if you hear anyone referring to the heresy of “antinomianism” as a grave danger, walk away, because you’re not going to hear them say much of anything else that is good or beautiful or true. When confronted by such rules-addled folks, it’s best to be as unruly as they say you are.

“What shall we say then? Shall we continue in sin, that grace may abound? God forbid.” That’s Paul in the earlier stages of the same long argument in which he later includes that line “Love is the fulfillment of the law.” Notice the rhetorical move Paul is making there — anticipating an absurd accusation and inoculating against it while simultaneously chiding those who imagine such an accusation is a reasonable response to what he’s saying about love as the fulfillment of the law.

In other words, Paul was rejecting the heresy of nomianism centuries before it occurred to any uptight Christians to start talking about antinomianism as a heresy, “for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.”

The historical rabbit hole of the “Antinomian Controversy” is also helpful as yet another example of how story prevails over rules when it comes to thinking about what is “moral” or “ethical.” This “controversy” is the story of Anne Hutchinson vs. the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. You can try to tell that story in a way that makes the Puritans technically correct, and Hutchinson technically unorthodox, but you’ll never manage to tell that story in a way that makes the Puritans come across as the Good Guys or that makes Hutchinson come across as the villain. (See also: Mary Dyer.)

What shall we say then? Get rid of all rules? Nah. Rules are OK, usually. They can be quite useful and practical, even necessary — particularly in contexts where we don’t have time to recite whole stories. But behind every rule there’s a story. And above every rule there’s a story. And the story matters more than any rule we use as a proxy or placeholder for it.

Of that story in John 8 Hart says, “it is a tale that in a sense refuses to leave us with any exact rule regarding any particular ethical situation, much less any single rule for all analogous situations.”

That would be much simpler. Just give us some “exact rules” for particular situations or, easier yet, a “single rule for all analogous situations.” But trying to construct, and abide by, and enforce such rules tends to turn us into the kind of people who want to stone women or to banish them from the colony or to hang them on the Boston Commons. Elevating rules, in other words, tends to turn us into the Bad Guys in whatever story we’re in.

If you still feel you want or need rules, here’s a good rule of thumb: Try not to be the Bad Guy in whatever story you’re in.

Or, in other words, “Love, and do what you will.” Because love is the fulfillment of the rules. (And it’s got panache.)