David Dark wrote about “Nashville’s entangled ‘Prayer Trade’” more than a year ago. Here are a few recent updates on that — the GodAndCountry Showbiz Spectacular — from a few different corners of Music City.

• Steve Rabey previews Leah Payne’s new book, God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music.

“Much of the top-selling CCM aimed at adults reflected the idea that American patriotism and social conservatism were synonymous with Christian orthodoxy,” she writes: “Ray Boltz’s 1994 ‘I Pledge Allegiance to the Lamb’ epitomized this blend of 1990s nationalism and premillennial dispensationalist angst. The music video featured a Christian father and son, persecuted for confessing Jesus Christ, mourning the 1962 Supreme Court decision banning sponsored prayer in public schools and ‘political correctness’ as inciting incidents of the apocalypse.”

Boltz later came out as gay, ending his CCM career. He now performs at LGBTQ-friendly churches.

“CCM” is a genre defined less by its musical style or its lyrical content than by the religio-political ideology of its white audience and the Nashville-based recording industry making money off of it.

• The Nashville Scene offers its “Country Music Almanac 2024: Our Journalists’ Survey.” The 16 writers and reviewers offer their picks for the best songs and albums of the past year, plus their biggest disappointments and their thoughts about the future of “what used to be called Country music.”

There’s a feast of great recommendations here — songs, albums, and artists loved by people who love music. But there’s also an unplanned common thread of lamentation that runs through all of the responses here, one represented by Jake Harris’ answer to the question about his biggest disappointment of 2023:

“Try That in a Small Town” by Jason Aldean. It’s everything wrong with the “small town” song in country music: nostalgia for a time and place that never existed in America, made by people who have never lived in the small towns they sing about, in order to pander to people who wish they lived in a romanticized version of those small towns. Meanwhile, the people who actually live in small towns are forgotten.

(As a suggested tonic to that noise, here’s Roberta Lea’s “Small Town Boy.”)

“Country” is a genre defined less by its musical style or its lyrical content than by the religio-political ideology of its white audience and the Nashville-based recording industry making money off of it.

• Nashville’s Regal Green Hills movie theater hosted a panel discussion last week to mark the screening of Dan Partland’s documentary God & Country, which includes interviews with several prominent members of the city’s thriving Prayer Trade.

Here’s the trailer:

The local angle for the paper is not just the local event, but the fact that the documentary features both Nashville-area white Christian nationalists as well as some prominent Nashville-based critics of white Christian nationalism. Three of the latter — former Southern Baptist honcho Russell Moore, anti-Trump conservative writer David French, and podcaster Christina Edmonson — took part in the panel discussion, led by Jemar Tisby, author of The Color of Compromise.

The weird thing about all of this is the framing of the article — starting with the headline: “Amid film backlash, evangelical leaders double down on denouncing Christian nationalism.”

It’s not clear if “film backlash” is supposed to mean a backlash against the film, or against Moore and French due to their appearing in the film.* Nor is it ever stated who is doing this lashing back.

“Moore’s story has represented a broader division within American evangelicalism between traditionalists who support former President Trump and those who don’t,” the story says.

That sentence is a mess. Does it intend to speak of the set of “traditionalists” who support Trump as opposed to the set of “traditionalists” who do not support Trump? Or does it mean two categories: Trump-supporting traditionalists on one side and everybody who is not specifically that on the other?

And what might “traditionalist” even begin to mean there?

It’s a synonym for “white,” I guess. That’s the only way the word makes any sense in this context. These nameless evangelical Tennesseans lashing back against Trump-critics like Moore and French are “traditionalist” in the sense that they voted for Trump just as their parents voted for Reagan and their grandparents voted for George Wallace. They’re keeping the faith and keeping the “tradition” alive by adapting its language over the years — just as the liturgist and ecclesiastic Lee Atwater described.

That is the variety of “backlash” and “outrage” that Moore’s story “represents” here:

Moore, the former president of the Nashville-based Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, which is the Southern Baptist Convention’s public policy arm, provoked outrage among some Southern Baptists for criticizing Trump. Eventually, he stepped down from the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission to join Christianity Today and left the SBC altogether.

It’s whitelash and whiterage. It’s racism. White evangelicals in Nashville — and everywhere else — are furious with Russell Moore and with David French due to their insufficient commitment to white racism. They are being rejected by the mass of white evangelicalism as race traitors.

None of this makes any sense until we acknowledge that this is what “traditionalists who support former President Trump” means.

The article, the panelists, and the backlashers ripping into Moore and French are all further confused by an additional level of euphemism and obfuscatory language.

Those on all sides of this “broader division” are adamantly anti-abortion and they’ve all completely absorbed the no-questions-allowed, absolutizing formula of this ideology that says anything and everything else must be set aside to oppose the Satanic baby-killers. It’s functioning for all of them just as it was designed to function, preserving their identity as “I am not a Satanic baby-killer and therefore I am a Good Guy despite [ ______ ]” just as it was meant to.

In response to their critics, Moore and French defensively reassert and reaffirm their adamant abortion-is-murderism as proof that their white evangelical standing ought to be above reproach. And here I think maybe their critics come closer to glimpsing the truth than Moore and French do themselves. They’re a bit closer than Moore and French are to realizing that abortion-is-murderism has always primarily been a device to allow white racists to tell themselves that they’re the Good Guys without ever repenting of white racism.

Alas, the language on all sides of that “broader division” in the niche world of white evangelicalism is so muddied by layers of proxy subject matter and euphemism and deliberate imprecision that they’re not able to think about it, let alone to talk about it, clearly.

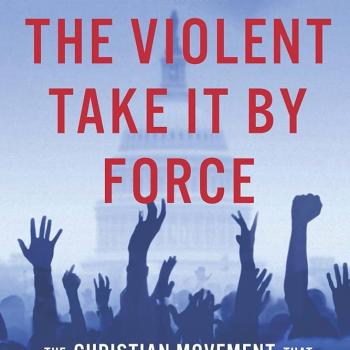

For example: We’re talking here about a documentary on “Christian nationalism.” The unsaid and unsayable thing that both those interviewed in that movie and those involved in the backlash to it understand is that “Christian nationalism” means “[white] Christian nationalism” and that, in turn, means just plain “white nationalism.”

What, exactly, is the difference between other forms of the “Prayer Trade” and unvarnished white nationalism?

The varnish.

* One recurring confusion involving this film and/or the “backlash” to it is the fact that Rob Reiner is among its many producers.

The semiotics of Rob Reiner turn out to be quite complex. He is a complex and polyvalent signifier.

It seems that Reiner’s name provokes an immediate, reflexive, venomous antipathy for certain strains of white [nationalist] evangelicals and Fox News viewers. They hate him. Hate hate hate hate hate him as much as Roger Ebert hated Reiner’s worst movie.

I think many of these folks are just olds who still think of Reiner as Meathead from All in the Family, a show they still resent 50 years later. Others see him as somehow the archetypal “Hollywood liberal.”

Whatever the words “Rob Reiner” mean to these people, it doesn’t seem to involve the actual person — the director who started his career with this incredible run of seven movies in an eight-year span: This Is Spinal Tap (1984), The Sure Thing (1985), Stand By Me (1986), The Princess Bride (1987), When Harry Met Sally (1989), Misery (1990), A Few Good Men (1992).

It’s odd that some of the same people who will reject Dan Partland’s documentary due to its guilt-by-association with Reiner’s production company will still rewatch and quote along with A Few Good Men every time it plays on cable.

Russell Moore, they’ll say, has no business being in a “Rob Reiner movie” even though they’d never say the same thing about, for example, Mandy Patinkin. They keep using that phrase, “Rob Reiner movie.” I do not think it means what they think it means.

Anyway, God & Country is not a Rob Reiner documentary, but the last such actual thing — Reiner’s celebration of his old friend and schoolmate, Albert Brooks: Defending My Life — is pretty terrific.